A tropical island in Tonga that appeared from the water in 2015 was filled with unique life forms, but the largest volcanic explosion of the twenty-first century utterly destroyed it along with the landmass, according to a new study.

The Pacific Ocean island of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai was created by volcanic activity in 2014 and 2015. Before being destroyed by the catastrophic Tonga eruption in 2022, it had a brief, seven-year lifespan that provided scientists with a unique opportunity to investigate how life emerges on new land masses.

And what they discovered astonished the scientists. The scientists discovered a strange species of germs that most likely originated from deep beneath rather than the bacteria families they anticipated would first occupy the island. On January 11, the researchers published their results in the journal mBio.

Nick Dragone, a doctorate candidate in the University of Colorado’s department of ecology and evolutionary biology and the lead study author, stated in a statement, “We didn’t observe what we were expecting.” Instead of the normal early coloniser species like cyanobacteria or creatures found when a glacier retreats, we discovered a special type of bacteria that metabolise air gases and sulphur.

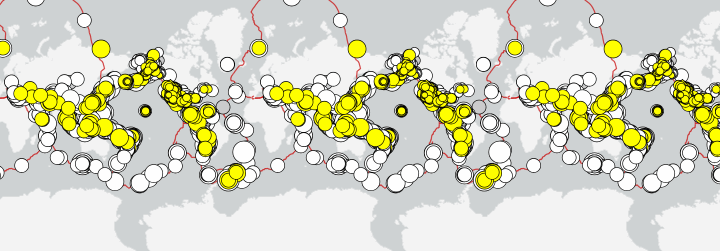

Following the eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai submarine volcano in December 2014, Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai began to build underwater in January 2015 and eventually formed a 0.7-square-mile (1.9-kilometer squared) island. It was named for the two islands it popped up between.

The researchers claim that Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai was the first tropical landmass to arise and survive for more than a year in the past 150 years, offering them a unique opportunity for further investigation.

The researchers took 32 soil samples from different non-vegetated areas ranging from sea level to the summit of the island’s crater, which rises 394 feet (120 metres), before extracting and analysing the DNA discovered there to determine which bacteria were residing on the new island.

Typically, scientists anticipate that bacteria from the water or from bird droppings will colonise new islands. However, the bacteria that consumed sulphur and hydrogen sulphide gas were the most common near the volcano’s cone, and it is possible that they reached the island’s surface via underground volcanic networks. 40% of the top 100 germs discovered by sequencing could not be assigned to a recognised bacterial family, according to the researchers.

The characteristics of volcanic eruptions, such as the abundance of sulphur and hydrogen sulphide gas, are thought to be a contributing factor in the presence of these unusual bacteria, according to Dragone in the statement. The bacteria resembled those in hot springs like Yellowstone, hydrothermal vents, and other volcanic systems the most. We believe that that are where the bacteria came from.

The volcano that had created the island eventually turned into its destructor. On January 15, 2022, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano erupted once more, this time with a force equivalent to more than 100 Hiroshima bombs detonating simultaneously and launching a plume of ash, island fragments, and steam halfway into space.

Although the island’s investigations were put to an end by the eruption, the short-lived landmass provided scientists with a framework for their subsequent work. “We all thought the island would remain. In fact, we were beginning to arrange a return trip the week before the island collapsed.” Dragone declared.

Although the island’s disappearance is regrettable, we can now make a number of predictions about what will happen when islands form. We would go there and gather further information if something were to form there once more. We would have a strategy for how to research it.