A reported case of bubonic plague in the UK has been identified as a false alarm. The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) has clarified that the report originated from a lab data mix-up in their weekly disease monitoring for England and Wales ending March 13.

“We do see occasional cases. Most are due to people coming into close contact with wild rodents while overseas,” said Professor Paul Hunter from the University of East Anglia. “Usually, it’s because people don’t realize that even cute-looking wild animals should be kept at arm’s length. The disease is spread by fleas.”

Plague Facts and Current Status

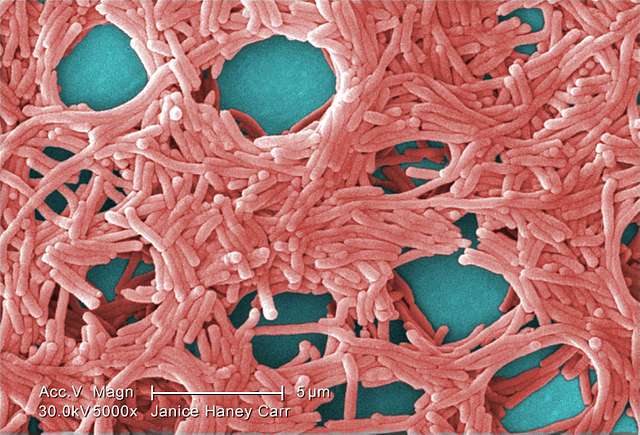

Bubonic plague, caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, typically spreads through flea bites or contact with infected animals. While once devastating, modern antibiotics make the disease highly treatable when caught early. However, untreated cases can still be fatal in up to 90% of patients within a week.

The World Health Organization estimates between 1,000-2,000 plague cases occur globally each year, primarily in parts of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The UK’s last significant outbreak happened in Suffolk in 1918.

Similar Posts

Vaccine Development Underway

Despite the false alarm, British scientists who contributed to COVID-19 vaccine development are working on a plague vaccine. This effort comes as the bacteria remains on Britain’s priority pathogens list – one of 24 infectious diseases being monitored as potential pandemic threats.

Historical Context

Plague is a bacterial disease that is infamous for causing millions of deaths due to a pandemic (widespread epidemic) during the Middle Ages in Europe, peaking in the 14th century wiping out approximately 60% of Europe’s population.

Recent plague cases have been documented in various countries including the US, Peru, and other countries. Last year, a case was reported in Oregon, US, likely passed on from a sick pet cat.

Frequently Asked Questions

Yes, but it’s much less threatening than in historical times. The World Health Organization estimates between 1,000-2,000 plague cases occur globally each year, primarily in parts of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Modern antibiotics make the disease highly treatable when caught early, though untreated cases can still be fatal in up to 90% of patients within a week.

Bubonic plague is primarily transmitted through flea bites or direct contact with infected animals. The bacteria Yersinia pestis that causes plague is carried by fleas that typically live on wild rodents. Humans can become infected when bitten by these fleas or when handling infected animals. As noted by Professor Paul Hunter, “Usually, it’s because people don’t realize that even cute-looking wild animals should be kept at arm’s length.”

The primary symptoms of bubonic plague include sudden onset of fever, headache, chills, weakness, and one or more swollen, tender, and painful lymph nodes (called buboes, which give the disease its name). These buboes typically appear in the groin, armpit, or neck. If left untreated, the infection can spread to other parts of the body and become life-threatening.

No, the recent report was a false alarm. The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) clarified that the report originated from a lab data mix-up in their weekly disease monitoring. The UK’s last significant outbreak happened in Suffolk in 1918.

Currently, there is no widely available vaccine for bubonic plague, but development is underway. British scientists who contributed to COVID-19 vaccine development are working on a plague vaccine. This effort comes as the bacteria remains on Britain’s priority pathogens list – one of 24 infectious diseases being monitored as potential pandemic threats.

The difference is dramatic. During the Middle Ages when plague killed approximately 60% of Europe’s population, there were no effective treatments. Today, bubonic plague is readily treatable with modern antibiotics if caught early. With prompt diagnosis and appropriate antibiotic treatment, mortality rates have dropped from 90% to about 10%. This highlights the importance of early medical intervention if symptoms appear after potential exposure.