The natural rhythms of British wildlife are experiencing major disruption as climate change continues to alter seasonal patterns, with some species showing alarming declines while others show signs of recovery in specific locations.

Early Spring Signals Growing Crisis

Data from Nature’s Calendar, a citizen science project by the Woodland Trust, reveals that spring events now occur nine days earlier compared to 25 years ago. In 2024, frogspawn appeared 17 days before the average date – the earliest on record.

“Warmer weather at the end of winter tricks species like the frog into thinking it’s time to start reproducing,” explains Alex Marshall from Nature’s Calendar. “That becomes a problem if early March frosts occur which can kill the developing tadpoles.”

Insects and Birds Show Worrying Decline

The National Trust’s annual report paints a concerning picture of wildlife populations across the UK. Butterfly numbers at the Giant’s Causeway dropped to half their typical levels, while gardens at Barrington Court in Somerset remained nearly devoid of butterflies until late August. In west Dorset, the adonis blue butterfly population plummeted from 552 in 2023 to just 92 in 2024.

Seabird populations faced similar challenges. The Farne Islands recorded historic lows, with common terns down 70%, sandwich terns 66%, and Arctic terns 51%. Sophia Jackson, area ranger, states: “The plummet in numbers is very shocking, especially because they have recently been added to the International Union for Conservation of Nature red list.”

Weather Extremes Take Their Toll

The shift from drought conditions in 2022-23 to an exceptionally wet and mild 2024 created additional pressures on wildlife. Ben McCarthy, the National Trust’s head of nature conservation and restoration ecology, notes: “The unpredictability of the weather and blurring of the seasons is adding additional stresses to our struggling wildlife. The overall trends are alarming.”

Storm impacts extended beyond wildlife to historic properties. Storm Henk caused unprecedented flooding at Avebury manor in Wiltshire – the first such incident in three centuries. At Bodnant Garden in north Wales, Storm Darragh brought down 30 “significant trees” including a “monster” Greek fir – Abies cephalonica – planted about 130 years ago.

Adaptation and Recovery

Despite the challenges, some species show resilience. Grey seals established Suffolk’s first colony at Orford Ness, with over 130 pups born last winter. The Sherborne Park estate in Gloucestershire recorded five breeding pairs of little owls, while Cornwall’s chough population grew by more than 100 for the second consecutive year.

Conservation efforts have yielded some positive results. The UK’s smallest dragonfly – the black darter – appeared in newly-created pools at Great Gnats Head on Dartmoor, demonstrating the potential for targeted habitat restoration.

Looking Ahead

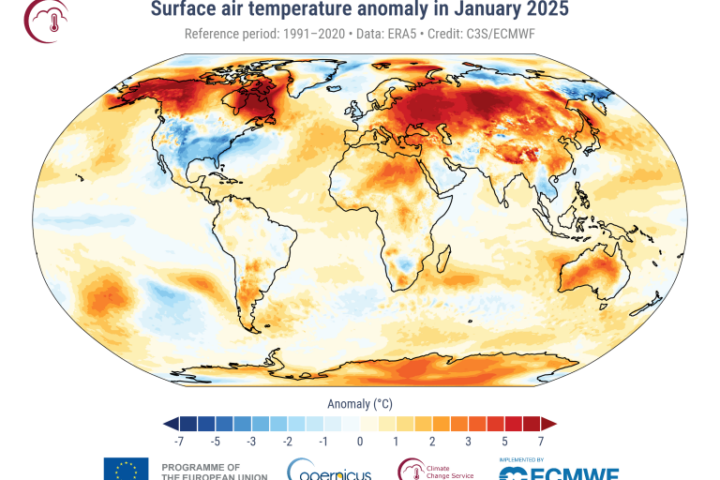

Scientists warn that 2025 could be the hottest year on record. Analysis by World Weather Attribution and Climate Central found that human-caused climate change added 41 days of dangerous heat across 2024, with 26 out of 29 studied weather events intensified by climate change.

Similar Posts

Keith Jones, climate change adviser at the National Trust, cautions: “As the world continues to get hotter, this trend hides a world of extremes – both deluge and drought and shifting patterns. The reality is now playing out in real time, impacting landscapes, nature and the places we look after.”

Additional Environmental Impacts

The ecological disruption extends to freshwater species. The River Wansbeck catchment lost approximately 70 white-clawed crayfish – Britain’s only native freshwater crayfish – with the cause still under investigation. Tree health has also suffered, with sycamores in eastern regions succumbing to sooty bark disease following the 2022 drought.