When Valdemar Postanovicz finished spraying his tobacco fields in remote Paraná, Brazil, he had no idea what was about to happen. Hours later, after showering, his nightmare began.

“All the right side of my body was paralysed. I couldn’t feel my foot and my hand. My mouth twisted to the right,” he recalls, describing what he initially feared was a stroke.

What Postanovicz experienced wasn’t a stroke but acute poisoning from Reglone – a herbicide containing diquat that’s banned on British farms but manufactured in Huddersfield, England, and legally exported to countries with weaker regulations.

The UK’s Toxic Export Business

An investigation by Greenpeace’s Unearthed and Swiss NGO Public Eye reveals a disturbing reality: in 2023 alone, the UK exported 8,489 tonnes of pesticides banned for domestic use due to health and environmental concerns. Of these exports, a staggering 98% came from Swiss-headquartered agrochemical giant Syngenta.

Diquat has emerged as the UK’s most exported banned pesticide, with Syngenta shipping 5,123 tonnes overseas last year – more than half destined for Brazil. This chemical has been prohibited on British and European farms since 2020 after experts determined it posed “high risks” to workers, residents near sprayed fields, and wildlife.

From Paraquat to Diquat: Brazil’s Toxic Switch

When Brazil banned the notorious weed killer paraquat in 2020 following evidence of poisonings and links to Parkinson’s disease, farmers quickly switched to diquat – a close chemical cousin. The result? Brazilian diquat usage skyrocketed from approximately 1,400 tonnes in 2019 to 24,000 tonnes in 2022 – a massive 1,600% increase.

This surge has had predictable consequences in Paraná, Brazil’s agricultural heartland. Between 2018 and 2021, the state recorded only 1-3 diquat poisoning cases annually. This jumped to six cases in 2022 and nine in 2023.

Marcelo de Souza Furtado, a specialist at the Paraná state health department who tracks poisonings, believes these numbers represent just “a small parcel of reality.”

“According to the World Health Organisation, for each poisoning registered, there will be 50 missed,” Furtado explains. “We’re worried. If it’s already been banned in other countries, then that already shows that it has a very toxic effect.”

The Personal Cost of Poisoning

For farmers like Postanovicz, the consequences are deeply personal. Despite wearing protective trousers, boots, and gloves while spraying, he omitted the recommended visor because “when we breathe it blurs all this plastic thing and we can’t see correctly.”

Even now, years after his poisoning incident, the smell of Reglone triggers visceral reactions. “I hate it. I can feel if someone is using it far from here, it is horrible,” he says.

For farmers like Postanovicz, the consequences are deeply personal. Despite wearing protective trousers, boots, and gloves while spraying, he omitted the recommended visor because “when we breathe it blurs all this plastic thing and we can’t see correctly.”

Even now, years after his poisoning incident, the smell of Reglone triggers visceral reactions. “I hate it. I can feel if someone is using it far from here, it is horrible,” he says.

Darley Corteze, a young farmer from Pérola d’Oeste in western Paraná, was shocked to learn about the double standard in diquat regulation. “I didn’t know about this, that they don’t use it in their country,” he says. “They manufacture it, send it abroad [but] don’t use it. Now I’m going to try to avoid using it, unless I have no other option.”

Beyond Occupational Exposure: Diquat and Suicide

The availability of toxic pesticides creates another disturbing risk. Between 2018 and 2022, Brazil officially registered 36 cases of diquat poisoning nationwide. Almost half (17) were suicide attempts, four of which were fatal.

Elza Patalo lost her son Luiz to diquat poisoning in February 2019 after he consumed Reglone during a moment of distress.

“It was 6 pm when he came into the kitchen and told me he had drunk Reglone,” Patalo recounts tearfully. “The next morning he was dead.”

Similar Posts:

His sister Luciana believes: “If he hadn’t had access to the pesticide, perhaps things could be different today, because it was easy for him to get it and drink the pesticide.”

According to Professor Michael Eddleston, an expert on pesticide poisoning at Edinburgh University, these circumstances illustrate why highly toxic pesticides in agricultural communities create public health hazards. Research in countries like Sri Lanka and China has shown that restricting access to highly hazardous pesticides can dramatically reduce suicide rates.

“We shouldn’t think of people drinking pesticides as people who want to kill themselves,” Eddleston explains. “They are not always doing that. They are self-poisoning to communicate And they do it with whatever is available.”

Regulatory Loopholes and Corporate Response

While countries like France and Belgium have already taken action to prohibit the export of banned pesticides, the UK has not followed suit. The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) states that the UK goes “beyond the international standard” by requiring consent from importing countries.

Syngenta defends its practices, stating: “Agricultural needs differ around the world and the use of agrochemical products is based on assessment by national governments of the risks and the benefits for use in their own country.”

The company claims that herbicides like diquat are “essential tools” for farmers implementing no-till farming practices, which can help reduce carbon emissions. They also assert that they provide extensive training on safe pesticide use – “over 55,000 individuals in Brazil alone” this year.

Safety Concerns and Protection Challenges

The European Food Safety Agency found that worker exposure to diquat could exceed the maximum acceptable level by more than 4000% – even when using recommended personal protective equipment (PPE).

While Syngenta’s Brazilian labelling for Reglone advises extensive PPE use (including coveralls, boots, gloves, a cap, an apron, goggles, and respiratory protection), Brazilian health officials acknowledge the practical challenges.

“The use of PPE is improving among local farmers but remains a significant cultural and practical challenge,” says Furtado. “Many farmers and workers either don’t use it or use only part of the equipment.”

Heat, humidity, and visibility issues make consistent PPE use difficult. Fábio Souza (name changed to protect his identity), another victim of diquat poisoning, wore a visor while preparing spraying equipment, but “the liquid came from below and reached my eye.” A year later, he still experiences blurred vision and burning sensations on sunny days.

The Ethical Question

For Dr. Marcos Orellana, the United Nations’ special rapporteur on toxics and human rights, the export of banned pesticides to developing countries represents a form of “modern-day exploitation.”

“It seems that for countries that produce and export banned pesticides, the life and health of people in recipient countries is not as important as their own citizens,” he states.

This sentiment is shared by many farm workers and their families in Paraná. As Luciana Patalo, who lost her brother to diquat poisoning, puts it: “I believe it is wrong to ban a pesticide in one country and send it to us. If it is dangerous for one population, it will be for the other one too.”

Looking Forward: Alternatives and Solutions

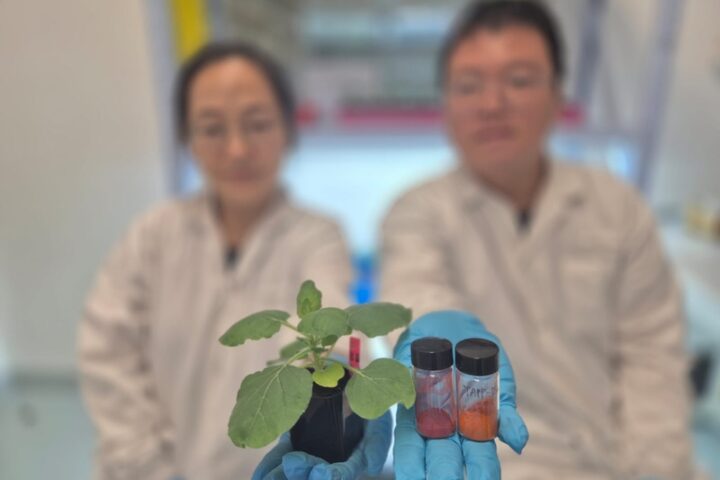

Research by the Pesticide Action Network has identified several alternatives to highly toxic pesticides, including:

- Living mulches and cover crops

- Controlled grazing

- Mechanical and thermal weeding

- Safer synthetic herbicides

- Integrated pest management approaches

As public awareness grows and more countries consider export bans, the pressure is mounting on governments and companies to address this regulatory disconnect. For now, thousands of farmers like Postanovicz are left to deal with the consequences of what he calls a “really strong product” that remains legally available despite being deemed too dangerous for British fields.

If you have questions on self-harm or feel suicidal, visit findahelpline.com to find an international helpline.

Frequently Asked Questions

Diquat is a herbicide used to control weeds and kill plants before harvest. It’s controversial because it’s banned in the UK and Europe due to serious health and environmental risks, yet it’s still manufactured in the UK and exported to countries with less stringent regulations like Brazil. Research has found that diquat poses “high risks” to agricultural workers, nearby residents, and wildlife, which led to its prohibition in British and European farms since 2020.

Yes. According to investigations by Greenpeace’s Unearthed and Swiss NGO Public Eye, the UK exported 8,489 tonnes of pesticides banned for domestic use in 2023 alone. About 98% of these exports came from Syngenta, a Swiss-headquartered agrochemical giant. Diquat was the UK’s most exported banned pesticide, with Syngenta shipping 5,123 tonnes overseas last year, more than half of which went to Brazil.

Diquat exposure can cause severe health problems. The article describes cases of acute poisoning resulting in symptoms like paralysis, loss of sensation, and facial drooping that mimic strokes. Even when using recommended protective equipment, the European Food Safety Agency found that worker exposure to diquat could exceed maximum acceptable levels by more than 4000%. Long-term effects can include persistent vision problems and sensitivity to chemicals. Beyond occupational exposure, diquat has also been used in suicide attempts, with fatal outcomes documented in Brazil.

Diquat usage in Brazil skyrocketed by 1,600% between 2019 and 2022 (from approximately 1,400 tonnes to 24,000 tonnes) because it became a replacement for paraquat, another toxic herbicide that Brazil banned in 2020. Farmers quickly switched to diquat, a close chemical cousin to paraquat, after the ban. This massive increase has been accompanied by a rise in diquat poisoning cases in agricultural regions like Paraná.

Syngenta defends its practices by stating that “Agricultural needs differ around the world and the use of agrochemical products is based on assessment by national governments of the risks and the benefits for use in their own country.” They claim that herbicides like diquat are “essential tools” for farmers implementing no-till farming practices that can help reduce carbon emissions. Syngenta also asserts that they provide extensive training on safe pesticide use, reaching “over 55,000 individuals in Brazil alone” this year.

Yes, according to research by the Pesticide Action Network, there are several alternatives to highly toxic pesticides like diquat. These include living mulches and cover crops, controlled grazing, mechanical and thermal weeding, safer synthetic herbicides, and integrated pest management approaches. As public awareness grows and more countries consider export bans, there’s increasing pressure on governments and companies to transition to these safer alternatives.