Surface ozone pollution, an often-overlooked air pollutant, poses a severe threat to India’s major food crops and could jeopardize the nation’s food security goals, according to new research from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kharagpur.

The Silent Crop Killer: Surface Ozone Explained

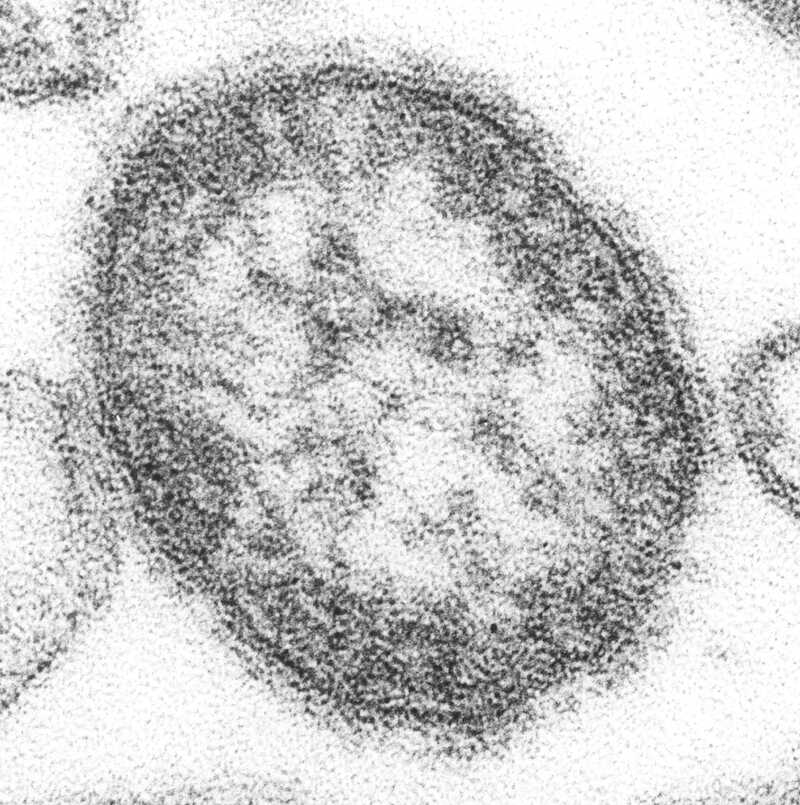

The study, led by Professor Jayanarayanan Kuttippurath at the Centre for Ocean, River, Atmosphere and Land Sciences (CORAL), examined how this potent oxidant damages plant tissues and reduces agricultural yields. Unlike particulate matter that often dominates air quality discussions, surface ozone works invisibly to harm crops at the cellular level.

“Surface ozone is a strong oxidant that damages plant tissues, leading to visible foliar injuries and reduced crop productivity,” the research team notes. When ozone enters plant leaves through tiny pores called stomata, it triggers oxidative stress, disrupting photosynthesis and impairing growth.

Alarming Projections for Key Crops

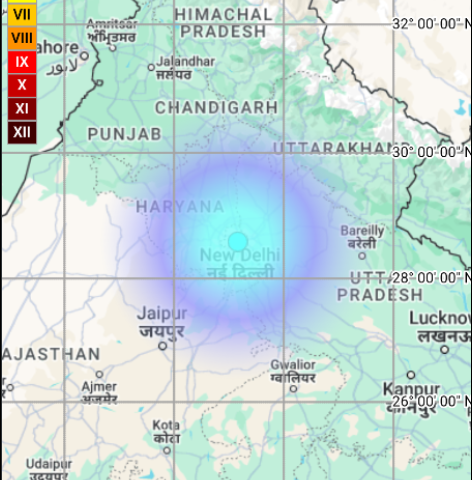

Using data from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase-6 (CMIP6), the research assessed historical trends and projected future ozone-induced yield losses for wheat, rice, and maize. The findings paint a troubling picture:

- Wheat could suffer an additional 20% yield reduction under high-emission scenarios with insufficient mitigation

- Rice and maize may experience losses of around 7%

- The Indo-Gangetic Plain and Central India face the highest risk, with ozone exposure potentially exceeding safe limits by up to six times

Food Security and Global Implications

These projected losses threaten India’s progress toward United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 1 (No Poverty) and 2 (Zero Hunger) by 2030. As a major food grain exporter to several Asian and African nations, diminished yields in India could ripple through global food supply chains.

The Ozone-Climate Connection

Surface ozone forms when nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) react in the presence of sunlight. Climate change exacerbates this problem through what scientists call the “ozone-climate penalty” – higher temperatures accelerate the chemical reactions that produce ozone, creating a dangerous feedback loop.

Research from the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) previously estimated that ozone pollution destroyed approximately 6 million metric tons of India’s wheat, rice, soybean, and cotton crops in 2005 alone, representing an economic loss exceeding US$1 billion.

Similar Posts

Policy Gaps and Rural Vulnerability

While India launched the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) in 2019 to combat urban pollution, agricultural regions remain largely unprotected. The NCAP primarily targets particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) reduction in urban areas, leaving a critical gap in monitoring and mitigating ozone pollution where food is grown.

“To protect crop health and ensure our food security, atmospheric pollution must be reduced and monitored,” Professor Kuttippurath’s team emphasizes.

Solutions and Path Forward

Experts recommend several approaches to address this threat:

- Implementing stricter controls on precursor emissions (NOx and VOCs) from vehicles, industry, and agricultural operations

- Developing ozone-tolerant crop varieties

- Establishing comprehensive rural monitoring networks

- Integrating ozone reduction strategies into agricultural policies

- Issuing timely ozone alerts to guide farming operations

The study, titled “Surface ozone pollution-driven risks for the yield of major food crops under future climate change scenarios in India,” was published in the journal Environmental Research and can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2025.121390.

As India balances development goals with environmental protection, addressing this invisible threat to food security requires immediate attention and coordinated action across sectors.

Frequently Asked Questions

Surface ozone is a ground-level air pollutant that forms when nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) react in the presence of sunlight. Unlike the beneficial ozone layer in the stratosphere that protects us from UV radiation, surface ozone is harmful to humans, plants, and crops. It acts as a strong oxidant that damages plant tissues and reduces agricultural productivity.

Surface ozone damages crops by entering plant leaves through tiny pores called stomata. Once inside, it triggers oxidative stress that disrupts photosynthesis, damages cell membranes, and impairs overall plant growth. This leads to visible leaf damage, premature aging of plants, reduced crop yield, and lower nutritional quality of harvested foods.

According to the IIT Kharagpur research, wheat is the most vulnerable crop, with projected additional yield losses of up to 20% under high-emission scenarios. Rice and maize are also significantly affected, with potential yield reductions of around 7%. Other crops like soybeans, cotton, and various vegetables are also susceptible to ozone damage.

The “ozone-climate penalty” refers to a dangerous feedback loop where climate change worsens ozone pollution. As temperatures rise due to climate change, the chemical reactions that produce surface ozone accelerate, creating more ozone. This increased ozone further damages crops and contributes to climate warming, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that threatens agricultural productivity.

India’s National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), launched in 2019, primarily targets particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) reduction in urban areas. It doesn’t adequately address surface ozone pollution, especially in rural agricultural regions where food is grown. This creates a critical gap in monitoring and protecting crops from ozone damage, leaving agricultural areas vulnerable.

Several approaches could help protect crops from ozone damage: implementing stricter controls on emissions of ozone precursors (NOx and VOCs) from vehicles, industry, and agriculture; developing ozone-tolerant crop varieties through breeding programs; establishing comprehensive rural air quality monitoring networks; integrating ozone reduction strategies into agricultural policies; and creating early warning systems to alert farmers about high-ozone days.