Malaysia’s last male Sumatran rhino, Kertam, died in 2019. Now, a team from the Max Delbrück Center has successfully grown stem cells and mini-brains from rhino’s skin cells. As they report in “iScience”, their goal is to use stem cell technology to create sperm cells that may help to save the endangered species from extinction.

The Last Of Their Kind In Malaysia

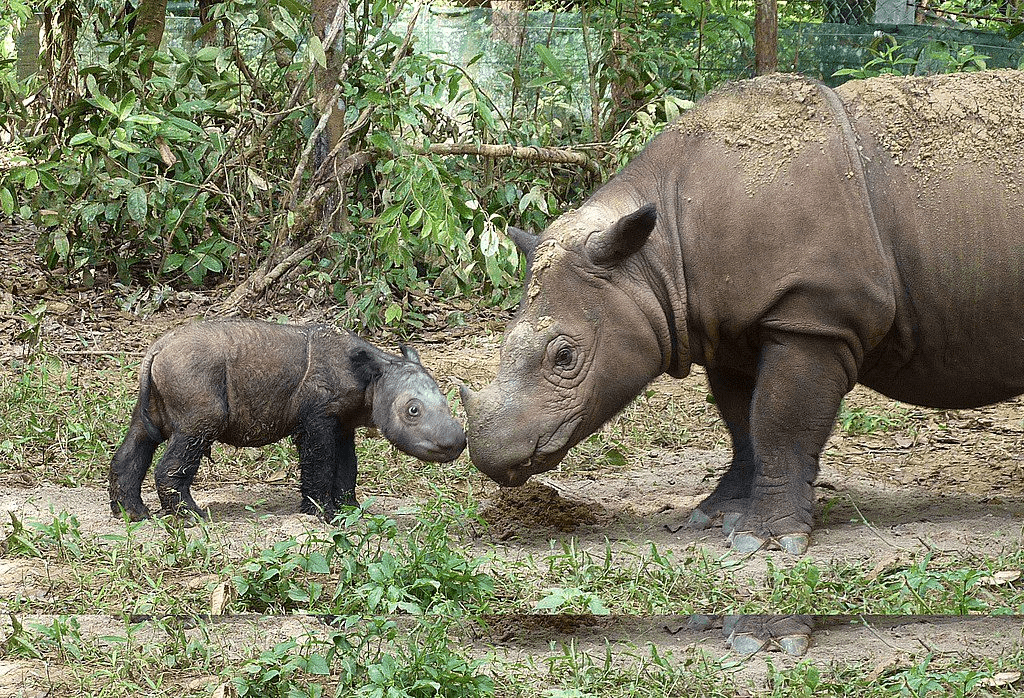

The Sumatran rhinoceros was once found across large parts of East and Southeast Asia. Today, poaching and habitat destruction have decimated the population of the world’s smallest and most ancient rhino species.

The Sumatran rhinoceros, which is the only surviving rhino species with hair, has been considered extinct in Malaysia since 2019 following the death of male Kertam and, just a few months later, female Iman. But a team of Berlin scientists led by Dr Vera Zywitza and Dr Sebastian Diecke, head of the Pluripotent Stem Cells Platform at the Max Delbrück Center in Berlin, were not content with this.

The team led by Zywitza and Diecke has now reported an initial success: they have generated induced pluripotent stem cells, or short iPS cells, from Kertam’s skin samples. These cells have two key advantages. First, they are able to divide infinitely and therefore never die; and second, they are able to transform into any cell type in the body. The group has already grown brain organoids, also called “mini-brains,” from Kertam’s iPS cells.

Learning From The White Rhino

The technology platform developed its stem cell technologies as part of the BioRescue research project for the even more critically endangered northern white rhinoceros. Professor Thomas Hildebrandt, head of the Reproduction Management Department at the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) in Berlin, and his research group were also significantly involved in the project.

Zywitza was pleased to discover that the methods used to turn the skin cells of northern white rhinos into stem cells also worked well with the cells of Sumatran rhinos. Under the microscope, the stem cells of both rhino species were barely distinguishable from human iPS cells. Zywitza explains that, in contrast to northern white rhino iPS cells, Kertam’s iPSCs could not be cultivated without feeder cells, which release growth factors that help to keep stem cells in a pluripotent state.

Another Peek Into Evolution

According to Zywitza, the stem cells obtained from Kertam’s skin serve another purpose of gaining insights into the evolution of organ development by providing unique tools from iPS cells of exotic animals. Dr. Silke Frahm-Barske, who is also a scientist in Diecke’s research group, grew brain organoids from the cells. However, she added that the team had to treat the human and rhino iPS cells slightly differently in order to cultivate the brain organoids.

The Next Step Is Sperm Cells

The team’s next goal is to use Kertam’s iPS cells to grow sperm suitable for artificial insemination. Zywitza stated that to obtain sperm cells, first they need to use the iPS cells to cultivate primordial germ cells, the precursors of eggs and sperm, which is a more difficult step. They also plan to obtain iPS cells from other Sumatran rhinos.

Reproduction expert Thomas Hildebrandt explains that by bringing together the Sumatran rhino wildlife reserves, measures are indeed being taken in Indonesia to preserve the remaining individual population. The females that have not been pregnant for a long time often become infertile, for example due to cysts that develop on their reproductive organs, or they may just be too old to bear young.

In addition, Zywitza stated even though their work is attempting to make the seemingly impossible possible, to ensure the survival of animals that would otherwise probably disappear from the planet, it must remain an exception and not become the rule. This can at best make a small contribution to saving these rhinos from extinction. The protection and conservation of the habitats is equally important.