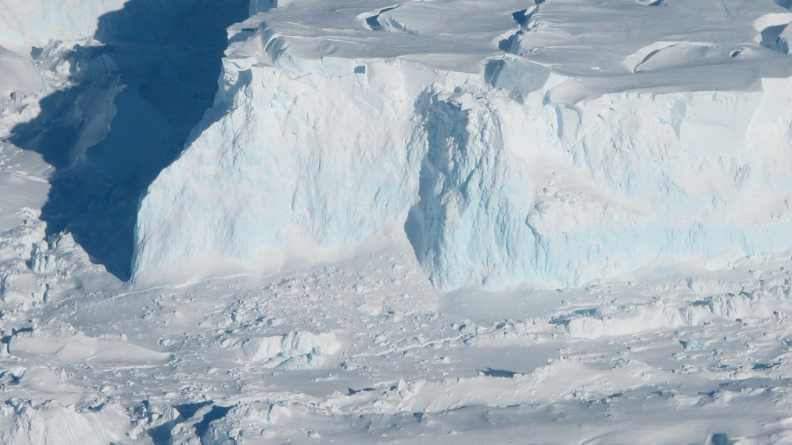

June 5 is observed as World Environment Day. It is fitting to know more about a glacier popularly known as “the Doomsday Glacier.” Owing to its geographical position, it is called so. Located in Antarctica, 2,800 km southwest of Cape Horn, Thwaites Glacier is comparable in size to Florida and is gradually melting, contributing significantly to the global rise in sea levels.

A layer of saltwater, 5 to 10 centimeters thick, penetrates up to 12 km beneath the glacier with each tidal cycle. This is revealed in a study led by Eric Rignot from the University of California. Involving 200 million cubic meters of seawater daily, this process lifts and sinks the glacier, increasing the melting process. The study carried out by researchers from the University of California, the University of Waterloo, and others estimates that this could result in the melting of 20 meters of the glacier base each year.

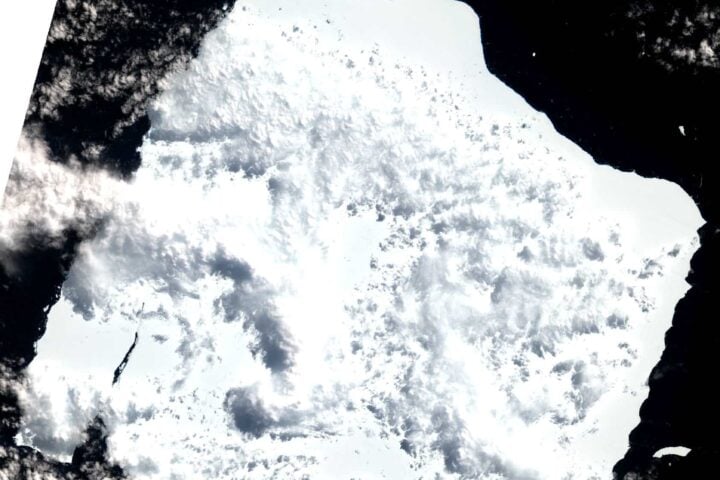

Glaciologists relied on data collected by the Finnish commercial satellite mission ICEYE, a Finnish microsatellite manufacturer, during the period from March to June 2023. The rise, fall, and curvature of the Thwaites Glacier were observed by the Finnish satellite. New insights have emerged from high-resolution satellite radar data. The data is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. These findings suggest a reevaluation of global sea level rise projections may be necessary.

“In the past, we had some sporadically available data, and with just those few observations it was hard to figure out what was happening. When we have a continuous time series and compare that with the tidal cycle, we see the seawater coming in at high tide and receding and sometimes going farther up underneath the glacier and getting trapped. Thanks to ICEYE, we’re beginning to witness this tidal dynamic for the first time said, ” said lead author Eric Rignot, UC Irvine professor of Earth system science

Similar Post

Employing InSAR technology, the ICEYE satellites provided a series of long-term daily observations. They reveal the dynamic interaction between the seawater and the ice. This interaction under the glacier leads to significant ice melt and may play a crucial role in understanding the rapid changes observed in Antarctic ice. Combined with geothermal flow and friction-induced freshwater, this interaction creates pressure that can lift large sections of the ice sheet.

Thwaites Glacier currently loses 75 billion tons of ice per year. According to NASA calculations, that accounts for half of Antarctica’s ice losses annually. Rignot, the researcher, believes the discovery has great scientific value because it will need to be included in computer simulations that predict future ice loss and sea level rise. He is confident they have found the key to understanding why Antarctic glacier ice melts faster than in laboratory experiments.

The study indicates, that seawater intrusions, extending kilometers beneath the anchored ice, may be the missing link between rapid past and present changes in ice sheet mass and the slower changes replicated by ice sheet models. Michael Wollersheim of ICEYE, co-author, said, “Until now, some of the most dynamic processes in nature have been impossible to observe with sufficient detail or frequency to allow us to understand and model them. Observing these processes from space and using radar satellite images, which provide centimeter-level precision InSAR measurements at daily frequency, marks a significant leap forward.”

Thwaites Glacier, also known as “the Doomsday Glacier,” located in Antarctica, is gradually melting, contributing significantly to the global rise in sea levels.”Thwaites is the most unstable place in the Antarctic and contains the equivalent of 60 centimeters of sea level rise,” said Christine Dow, Co-author, professor in the Faculty of Environment at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada.

“At the moment we don’t have enough information to say one way or the other how much time there is before the oceanwater intrusion is irreversible. By improving the models and focusing our research on these critical glaciers, we will try to get these numbers at least pinned down for decades versus centuries. This work will help people adapt to changing ocean levels, along with focusing on reducing carbon emissions to prevent the worst-case scenario.” concluded Christine Dow.

![Big city Los Angeles smog building [photo source: pixabay] [PDM 1.0]](https://www.karmactive.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/46-of-Americans—156-M—Now-Breathe-Hazardous-Smog-and-Soot-State-of-the-Air-Report-Exposes-Decade-High-Pollution-1-150x150.jpg)