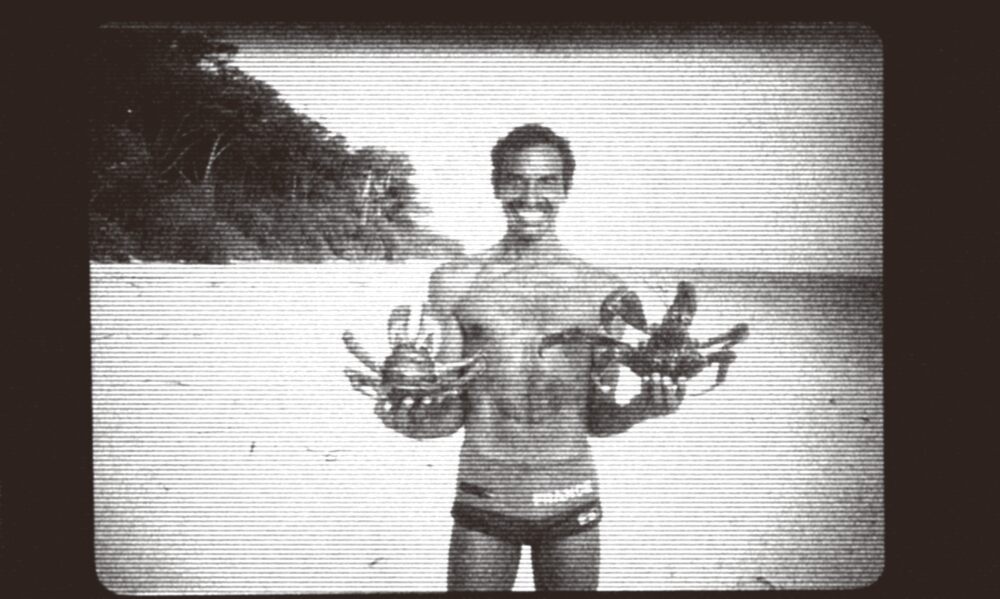

Back in the early 1970s, when conservation was barely a whisper in India’s environmental consciousness, a quiet young man from IIT Madras was already swimming against the current. Satish Bhaskar, known to his hostel mates as “Aquaman,” would soon become the country’s first dedicated sea turtle researcher, embarking on a journey that would cover more than 4,000 kilometers of India’s coastline on foot.

Having watched conservation efforts evolve over five decades, I can say with certainty that few individuals have made such lasting contributions with so little fanfare. In today’s world of instant recognition, Bhaskar’s story stands apart—a testament to fieldwork conducted not for acclaim, but for the survival of ancient marine species.

From Engineering Student to “Turtle Walker”

The trajectory began modestly at the Madras Snake Park, established by Rom Whitaker near IIT Madras. While his engineering classmates pursued conventional careers, Bhaskar was drawn to the nascent conservation work happening at the park. Initially, he joined night patrols along Chennai’s beaches to protect olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) nests from poachers, which soon evolved into a more formal role.

“I suggested to him that India needs a Mr. Sea Turtle, and he would be the ideal man for the job,” Rom Whitaker recalls. With minimal resources—a stipend of just Rs. 250 per month—Bhaskar began what would become the first comprehensive study of sea turtle nesting across India.

Between 1977 and 2001, Bhaskar conducted groundbreaking surveys that established baseline data critical for conservation planning. His expeditions covered:

- The Gulf of Mannar (1977): His first formal survey

- Lakshadweep Islands (1978, 1982): Identifying significant green turtle (Chelonia mydas) nesting sites

- Gujarat coast (1978): Mapping nesting beaches along western India

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands (1979-1990s): Multiple surveys documenting leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) and green turtle nesting

- Mainland coasts of Kerala, Goa, Andhra Pradesh, and Odisha: Establishing the first scientific records of turtle nesting

The Suheli Island Experiment

The scientific value of these surveys cannot be overstated. “In Chennai, we had just started the turtle walks through the Students’ Sea Turtle Conservation Network. As youngsters, we were all in awe of all the things that he had done, which of course we heard about from Rom Whitaker, Harry Andrews and others. Satish was too self-effacing to tell the stories, other than in a completely matter-of-fact way,” notes Kartik Shanker, sea turtle biologist and chairperson at the Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science.

In 1982, Bhaskar undertook what might be his most legendary field mission—marooning himself on the uninhabited Suheli island in Lakshadweep during the monsoon season. For over three months, he lived in isolation to document green turtle nesting behavior during the peak season when no boats could reach the island.

This expedition demonstrated both his scientific dedication and physical resilience. When a dead whale shark washed ashore, the overpowering stench forced him to relocate his camp to a precarious sand spit at the other end of the island. When provisions ran low, he survived on milk powder, turtle eggs, clams, and coconuts.

Famously, he sent a message in a bottle that traveled over 800 kilometers, reaching a Sri Lankan fisherman who found it 24 days later and mailed the letter to Bhaskar’s wife. While portrayed romantically in accounts, Bhaskar characteristically explained it as “an experiment to study ocean currents.”

Bhaskar’s meticulous work gained global attention. In 1979, he presented findings at the World Conference on Sea Turtle Conservation in Washington, D.C., becoming one of the first Asian researchers to document sea turtle populations in the eastern Indian Ocean.

In 1984, he received the prestigious Rolex Award for Enterprise. Later expeditions took him to West Papua, Indonesia, where he tagged over 700 leatherback turtles at Jamursba Medi and Wermon beaches, documenting 13,360 nests—data crucial for understanding population dynamics in the region.

The International Sea Turtle Society awarded him their Annual Sea Turtle Champion Award in 2010, recognizing his pioneering contributions. Characteristically, Bhaskar declined to collect the award publicly.

Similar Posts

Living on the Edge: Physical Challenges and Close Encounters

What separates Bhaskar’s work from contemporary research is the physical hardship he endured. Without modern technology, GPS, or satellite communications, his work relied on personal endurance and resourcefulness.

On South Reef Island in the Andamans, he studied hawksbill turtles while swimming dangerous channels to Interview Island for freshwater. During one such trip, he had a close encounter with a feral elephant that charged him—forcing him to throw down his shirt as a distraction and flee. The next day, he found his shirt torn to pieces.

His letters described enduring sandflies and mosquitoes during the day and night in the Nicobars. Once while sleeping on a beach on Trinkat Island, he awoke to find a young saltwater crocodile examining him through his mosquito net.

“To him, swimming in shark-infested waters was the most normal thing to do,” declares Shekar Dattatri, who has known him since the early Snake Park days.

Scientific Contributions Beyond Sea Turtles

While primarily focused on marine turtles, Bhaskar’s fieldwork yielded broader scientific value. During expeditions with herpetologist Indraneil Das, they discovered five new species—two frogs, two lizards, and a snake in the Nicobar Islands.

He also conducted extensive surveys of the Northern River Terrapin (Batagur baska), earning him the nickname “Batagur Bhaskar.” His findings confirmed this species was nearly extinct in the wild in India due to overharvesting, information that proved critical for subsequent conservation programs.

Bhaskar’s detailed reports did more than document species—they directly influenced conservation policy. His were the first recommendations on sea turtle nesting beach protection. These helped give the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Forest Department a solid conservation basis to resist the efforts of big business and other government department interests in “developing” beaches for tourism,” notes Rom Whitaker.

When a UNDP-Wildlife Institute of India project conducted nationwide sea turtle surveys, researchers found they were essentially updating Bhaskar’s original work from decades earlier. His baseline data became the standard against which population changes were measured.

Personal Ethics and Character

Among the most striking aspects of Bhaskar’s career was his ethical approach to fieldwork. During one expedition with Indraneil Das in the Nicobars, they encountered local tribal people after running out of food and water. Bhaskar declined their offers of food, later explaining they had nothing to repay the kindness.

Despite his tremendous appetite, he could survive on minimal provisions. His ascetic lifestyle—he was a teetotaler and non-smoker—contrasted with many peers. He maintained this simplicity throughout his career, even after receiving international recognition.

“He is a perfectionist—wanting to do everything right and better than anybody else. He also has an exaggerated sense of justice—always rooting for the downtrodden,” observed Rom Whitaker.

In 2018, filmmaker Taira Malaney convinced Bhaskar to return to the Andamans for a documentary about his life. During this visit to South Reef Island, where he had monitored hawksbill turtles in the 1990s, Bhaskar—then 72—reportedly shed his clothes, put on fins, and swam to the island when the boat couldn’t land due to topographical changes after the 2004 tsunami.

The resulting documentary, “Turtle Walker,” premiered at Doc NYC and won the Grand Teton Award at the Jackson Wild Media Awards. The film was subsequently screened at the DC Environmental Film Festival in 2025.

After declining health, Bhaskar passed away in March 2023, his wife died in October 2022. He is survived by his three children, Nyla, Kyle, and Sandhya.

Modern Conservation Building on His Foundation

Climate change presents challenges that make his baseline data even more valuable. Rising sea levels, beach erosion, and altered nesting conditions are being studied by comparing current observations with his historical records. His work provides critical context for understanding how nesting patterns have shifted over time.

Organizations like the Andaman and Nicobar Environmental Team (ANET), the Dakshin Foundation, and the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust continue research and conservation in the areas Bhaskar first explored. His legacy lives on through the scientists and conservationists he inspired.

In an age of environmental despair, Bhaskar’s story provides a reminder that dedicated field science, conducted with patience and persistence, remains the foundation of effective conservation.