The United States has lost its only known population of the Key Largo tree cactus, marking what scientists believe is the first local plant extinction in the country directly caused by sea-level rise.

Once thriving with about 150 stems in North Key Largo, Florida, this impressive cactus (Pilosocereus millspaughii) has vanished from its natural habitat due to saltwater intrusion, soil depletion, and hurricane damage. While the species still grows in scattered locations in the Caribbean, including northern Cuba and parts of the Bahamas, it no longer exists naturally in the U.S.

“Unfortunately, the Key Largo tree cactus may be a bellwether for how other low-lying coastal plants will respond to climate change,” said Jennifer Possley, director of regional conservation at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden and lead author of the study documenting the population’s decline.

A Unique Florida Species

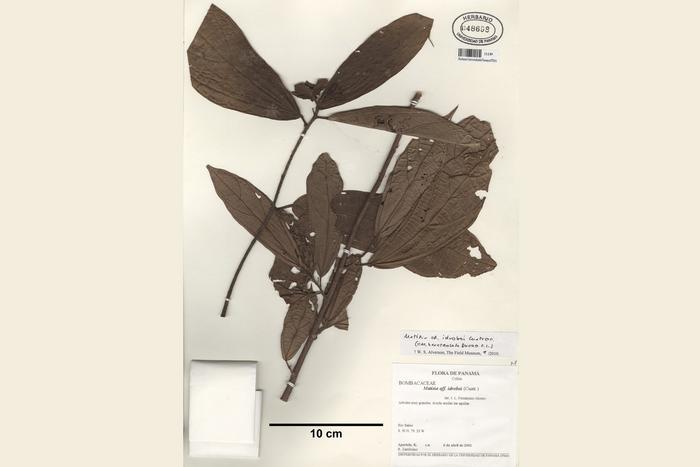

First discovered in the U.S. in 1992, the Key Largo tree cactus was initially mistaken for the similar-looking, federally endangered Key tree cactus (Pilosocereus robinii). Both species can grow more than 20 feet tall with cream-colored, garlic-scented flowers that attract bat pollinators and produce bright red-purple fruits enjoyed by birds and mammals.

The Key Largo tree cactus stood out with its distinctive thick tufts of woolly white hairs at the base of flowers and fruits—so dense they resembled snow—and spines twice as long as those of its relative. Alan Franck, herbarium collection manager at the Florida Museum of Natural History, confirmed in 2019 that this was indeed the first and only known population of Pilosocereus millspaughii in the United States.

Tracking the Decline

Scientists have documented the cactus population’s steady decline over years of monitoring:

- By 2015, researchers found only 60 live plants—a 50% drop from their previous count in 2013

- By 2016, only 28 rooted stems remained—another 50% reduction

- By 2021, just six ailing stems were left

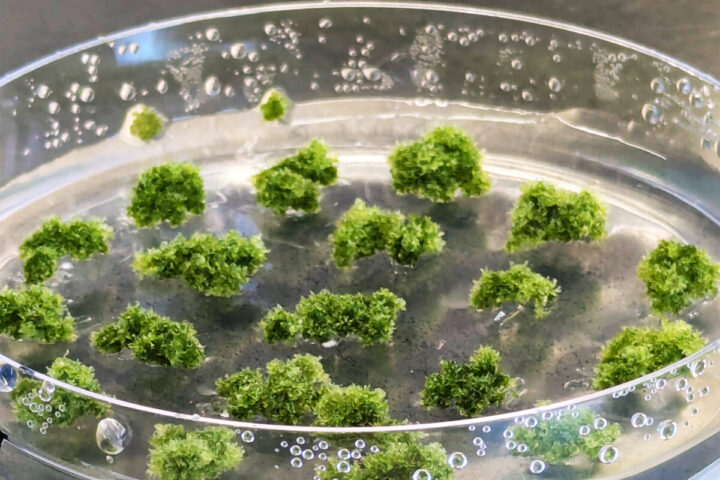

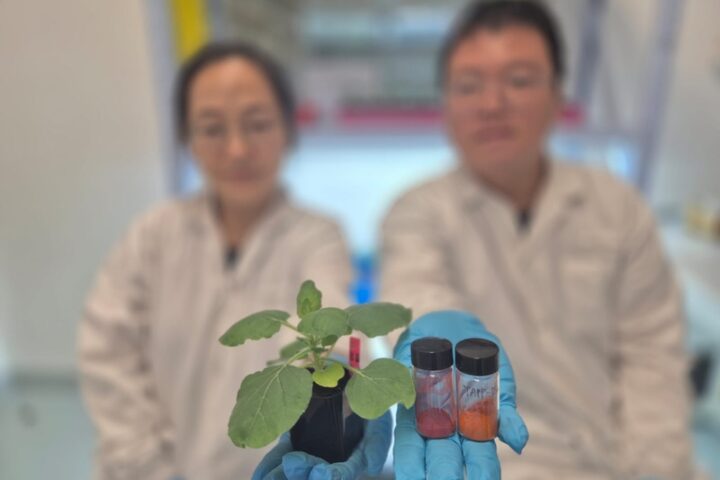

The final six stems were removed to greenhouses in 2021 after it became clear the population wouldn’t survive in the wild. Researchers salvaged all remaining green material to grow in controlled settings, hoping to preserve the species.

“It was one of the things that made the Keys so special,” said James Lange, research botanist at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden and study co-author. “Just a big, bold, beautiful plant.”

Similar Posts

Multiple Threats Converged

The cactus grew on a low limestone outcrop surrounded by mangroves near the shore. Several environmental factors contributed to its extinction:

Rising Sea Levels: The Florida Keys have experienced sea-level rise of 4.09 millimeters per year between 1971 and 2022. As sea levels rose, saltwater began penetrating further inland.

Soil Erosion: Storm surges from hurricanes and high tides gradually washed away the soil and organic matter where the cacti grew.

Saltwater Intrusion: Researchers found higher salt levels in soil beneath dead cacti compared to living ones, establishing a clear link between salinity and mortality.

Herbivory: In 2015, researchers discovered significant herbivore damage to the cacti. As Lange explained, “We noticed the first big problem in 2015. When we arrived to evaluate the plants that year, half of the cacti had died, apparently from an alarming amount of herbivory.” The animals may have targeted the water-storing cacti during periods of freshwater scarcity.

Hurricane Damage: Hurricane Irma in 2017 created a 5-foot storm surge that flooded large portions of Key Largo for days.

King Tides: In 2019, exceptionally high “king tides” left the area flooded for over three months.

Salt-tolerant plants that had previously been restricted to brackish soils beneath the mangroves began creeping up the outcrop, signaling increasing salt levels in the soil.

Limited Options for Survival

The cactus population had nowhere to retreat as conditions worsened. “They inhabit a small island of upland habitat, surrounded by mangrove forest, which has a wet, mucky substrate, and would not support this cactus’ growth. The nearest suitable habitat was too far away for dispersal,” Possley explained.

Since 2000, 19 named hurricanes have impacted the Florida Keys, with increasingly severe effects on the fragile ecosystem. About 90% of the Florida Keys Island chain sits at just 5 feet of elevation or less, with NASA predicting future ocean rise of up to 7 feet by 2100.

Conservation Efforts

Researchers from Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection have “tentative plans” to replant some cultivated specimens in the wild. Similar efforts have helped maintain the related Key tree cactus, which faces similar threats.

“The amount of reintroduced material of this species is already more than the amount of wild material that’s left,” Possley noted. However, she added that this might be “more of a stopgap than a solution” because environments suitable for tree cacti are disappearing.

“It’s generally a fringe between the mangroves and upland hammocks called thorn scrub, and there just aren’t many places like that left where we can put reintroduced populations,” she said.

Wider Implications

The extinction highlights the real-world impacts of climate change on coastal ecosystems. Rather than a smooth, predictable rise in sea or salt levels, the reality manifests as a complex series of related events that put additional pressure on already stressed species.

“We are on the front lines of biodiversity loss,” said study co-author George Gann, executive director for the Institute for Regional Conservation. “Our research in South Florida over the past 25 years shows that more than one-in-four native plant species are critically threatened with regional extinction or are already extirpated due to habitat loss, over collecting, invasive species and other drivers of degradation. More than 50 are already gone, including four global extinctions.”

The study was published in the Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas in July 2024.