Portland, Oregon is grappling with a sharp rise in dysentery cases, a disease many Americans know from the 1980s video game “Oregon Trail.” The real-world outbreak has reached concerning levels, with Multnomah County reporting 158 cases in 2024—a 62-case jump from 2023—and 40 new cases in January 2025 alone.

The Numbers Tell a Troubling Story

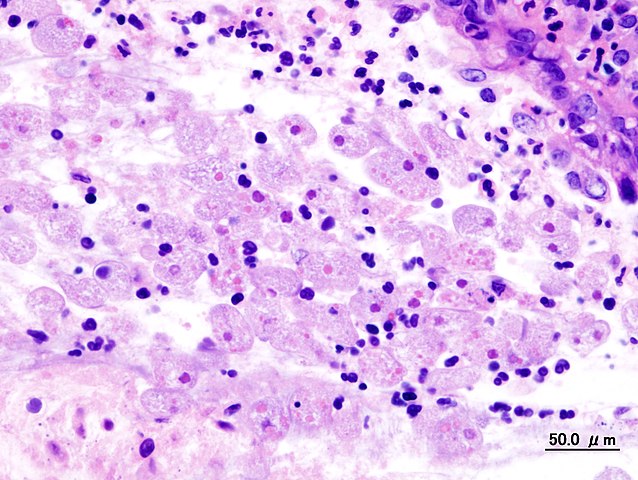

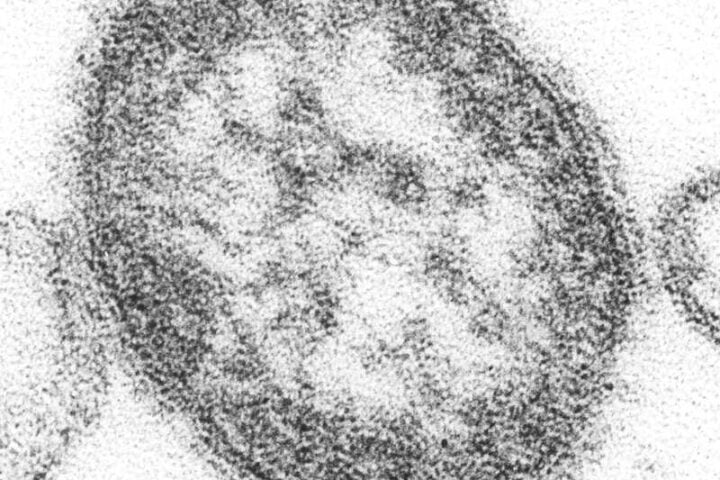

The current spread involves shigellosis, the most common form of dysentery caused by Shigella bacteria. County health data reveals that 56% of cases occur among people experiencing homelessness, while 55% of those affected report methamphetamine and/or opiate use.

“Housing is related to nearly all aspects of health, including infectious diseases,” the Multnomah County Health Department told KOIN. “Lacking housing creates a context that can increase the risk of multiple kinds of infectious disease.”

A Public Sanitation Problem

With approximately 6,000 people living outdoors in Multnomah County, the mere 116 public restrooms in Portland present a severe infrastructure gap. Many of these facilities close during winter or at night, further limiting access to basic sanitation.

Dr. John Townes, medical director for infection prevention and control at Oregon Health & Science University, offered a straightforward solution: “If you want to stop an outbreak of shigella, you give people toilets and soap and water. And you train them in how to wash their hands.”

The Human Impact

J.W. Mosher, who believes he contracted the bacteria while cleaning toilets at the Clark Center (a residential program for men in the county justice system), described his experience: “It’s no fun. I just had uncontrollable diarrhea for two weeks before I went to the hospital.”

At the Clark Center, Transition Projects CEO Tony Bernal stated, “We have not had any additional reports of shigella in our facility, and we are monitoring the situation closely. We do have a standard procedure to regularly and frequently clean restrooms, showers, and other shared spaces—including routine deep cleaning.”

Similar Posts:

Previous Attempts and Challenges

The city previously tried addressing similar issues by placing 123 portable toilets near homeless encampments at a cost of $75,000 monthly. However, these facilities faced widespread vandalism—every unit was damaged, with 30 deemed total losses. Housed neighbors sometimes actively opposed their installation.

Opening park bathrooms year-round isn’t simple either. Parks spokesperson Mark Ross explained that winter-closed facilities would need “an extensive system wide evaluation of plumbing and infrastructure” to prevent pipes from bursting in freezes—a project requiring “significant capital expense” that the bureau currently lacks funding for.

Medical Response and Antibiotic Resistance

Most people with dysentery are advised to drink fluids, rest, and wash hands regularly. The county has implemented a temporary housing program for those with infectious diseases, helping 24 people since its summer launch—20 of whom had shigellosis.

Medical professionals note the bacteria in circulation aren’t among the most dangerous strains, though infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals face higher risks. Concerningly, several Shigella bacteria have developed antibiotic resistance.

“That is a major concern,” Dr. Townes said. “We can’t just give antibiotics willy-nilly for these infections. If a patient is not very sick, the best thing is to isolate them and let it run its course.”

The Broader Public Health Challenge

Dr. Amanda Risser of Central City Concern sees the root issue clearly: “Pretty much every day I go to work, I see human poop outside and that’s new. I think people poop outside when they don’t have anywhere else to poop.”

Adam Solano, dispatch manager for Ground Score (the organization cleaning Portland’s streets), confirms receiving calls about human waste from clean-up crews two to six times daily, requiring the city’s biohazard removal team.The county has allocated $337,033 for a communicable disease supportive housing pilot program this fiscal year, aiming to help 50 people by June and limit the spread of infectious diseases.