More than 17 million insects migrate each year through a single mountain pass on the border between France and Spain, according to new research. Scientists from the University of Exeter have studied migratory insects at the Bujaruelo Pass, a 30-meter gap between two high peaks in the Pyrenees. Their article, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, is titled “The Most Notable Migrants: A Systematic Analysis of the Migration Route of Insects in Western Europe through a Mountain Pass in the Pyrenees.”

The team visited the pass every autumn for four years, monitoring the large quantity and variety of diurnal flying insects heading south. The findings from this unique pass suggest that billions of insects cross the Pyrenees each year, making it a key location for many migratory species. Migratory insects begin their journeys farther north in Europe, including the UK. “More than 70 years ago, two ornithologists – Elizabeth and David Lack – chanced upon an incredible spectacle of insect migration at the Pass of Bujaruelo,” said Will Hawkes, from the Centre for Ecology and Conservation at the Penryn Campus of Exeter in Cornwall. “They witnessed a remarkable number of hoverflies migrating through the mountains, the first recorded case of fly migration in Europe. In 2018, we went to the same pass to see if this migration still occurred, and to record the numbers, species, weather conditions and ecological roles and impacts of the migrants.”

Similar Post

The researchers used a video camera to count the small insects, visual counts to quantify butterflies, and a flight interception trap to identify migrating species. “What we found was truly remarkable,” Hawkes continued. “Not only were vast numbers of marmalade hoverflies still migrating through the pass, but far more besides. These insects would have begun their journeys further north in Europe and continued south into Spain and perhaps beyond for the winter. There were some days when the number of flies was well over 3,000 individuals per metre, per minute.”

The team leader, Dr. Karl Wotton, said, “To see so many insects all moving purposefully in the same direction at the same time is truly one of the great wonders of nature.” The number of insects peaked when conditions were warm, sunny, and dry, with low wind speeds and headwinds to keep the insects low over the pass for counting. Dr. Wotton continued, “The combination of high-altitude mountains and wind patterns render what is normally an invisible high-altitude migration into a this incredibly rare spectacle observable at ground level.”

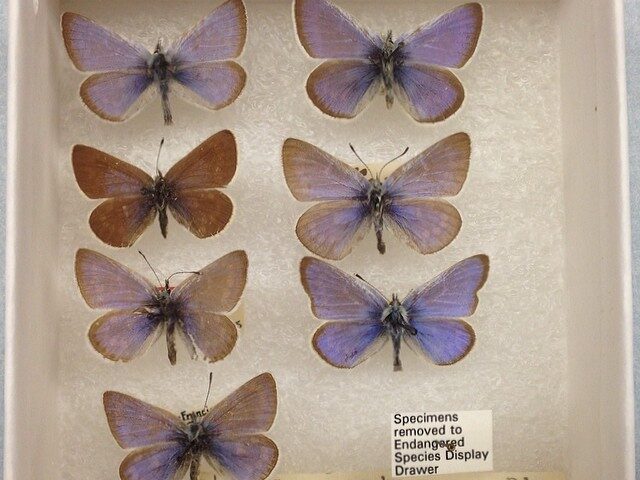

A variety of insects were seen, but flies constituted 90% of the total. Butterflies and dragonflies are well-known migratory insects, but they represent less than 2% of the total. Many of the migrants were familiar garden inhabitants, such as the cabbage white butterfly (Pieris rapae), the housefly (Musca domestica), and even tiny grass flies (Chloropidae), just 3 mm long. Hawkes added, “It was magical. I would swing my net through seemingly empty air and it would fill with the tiniest flies, all traveling in this incredibly huge migration.”

These migratory insects, especially flies, are of enormous importance to our planet. Almost 90% of the insects were pollinators and, by migrating, they carry genetic material over long distances between plant populations, enhancing plant health. Some of the insects were pest species, but many were pest controllers, including hoverflies and syrphid flies that feed on aphids in their larval stage. Many play a role in decomposition, and all transport nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen over long distances, which could be important for soil health and plant growth.

Due to the climate crisis and habitat loss, these vital migratory insects are believed to be declining. Hawkes concluded, “By spreading the knowledge of these remarkable migrants, we can spread interest and determination to protect their habitats. Insects are resilient and can bounce back quickly. Together, we can protect these most remarkable migrants of all.”