In just a decade, South Africa’s Gansbaai Bay transformed from a thriving great white shark haven to an ecosystem dramatically altered by the emergence of specialized orca predators. What began with a mysterious shark death in 2017 has evolved into a remarkable case study of marine predator dynamics and their cascading effects on ocean ecosystems.

The transformation began on February 8, 2017, when a 2.6-meter female great white shark washed ashore in South Africa. Dr. Alison Towner, a marine biologist from Rhodes University, noted the absence of typical human-caused injuries like hook or net marks. This marked the beginning of a pattern that would reshape the region’s marine ecosystem.

“It’s all about observing one of the world’s most impressive predators in its natural habitat in the company of researchers from all over the world,” remembers Dr. Towner on a podcast with the Save Our Sea Foundation.

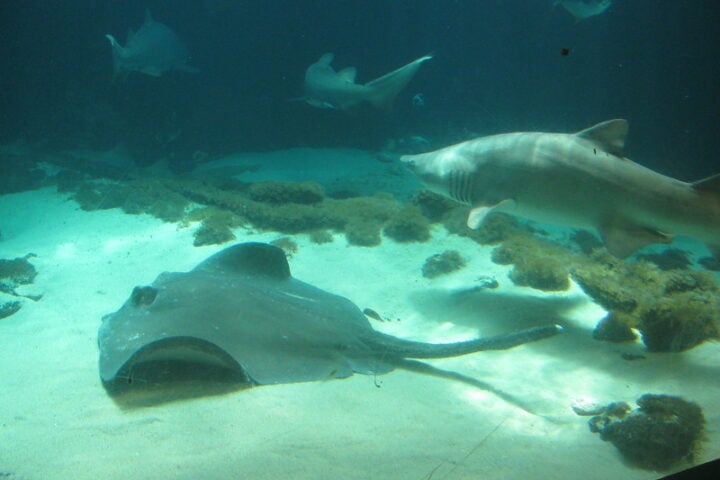

Two male orcas, nicknamed Port and Starboard for their distinctively collapsed dorsal fins, have emerged in Gansbaai since 2015. These killer whales demonstrated unprecedented hunting behavior. Their surgical precision in removing shark livers became their signature, leading to a dramatic decline in the local great white population.

The turning point came on May 16, 2022, when drone operator Christiaan Stopforth captured conclusive evidence: orcas, including Starboard, attacking and killing a white shark in Mossel Bay. The attack lasted merely two minutes, showcasing the orcas’ efficient hunting strategy.

“Killer whales are highly intelligent and social animals. Their group hunting methods make them incredibly effective predators,” said marine mammal specialist Dr Simon Elwen, Director of Sea Search and a research associate at Stellenbosch University.

The impact on shark populations has been severe:

- Gansbaai’s great white population dropped from 800-1,000 in the 2010s to sporadic sightings

- Surviving sharks fled up to east to areas like Plettenberg Bay

- By 2024, Mossel Bay recorded fewer than 10 confirmed great white sightings

Similar Posts

The disappearance of great whites has triggered significant ecological changes. As “doctors of the ocean,” their absence has led to:

- Increased populations of cape fur seals and bronze whaler sharks

- Increased predation on endangered African penguins by emboldened seals

- A spread of rabies among seal populations in the Western Cape since June 2024, reaching Mossel Bay in July

Dr. Towner suggests that maintaining previous great white population levels might have helped control the rabies situation, as infected seals would have been more vulnerable to predation.

While Port and Starboard’s hunting has transformed local ecosystems, an even greater threat looms over shark populations worldwide. Recent studies by Professor Nicholas Dulvy at Simon Fraser University reveal that human activities, particularly overfishing, have halved global shark abundance since 1970. Over 100 million sharks are killed annually through fishing, with more than a third of shark species now facing extinction risks.