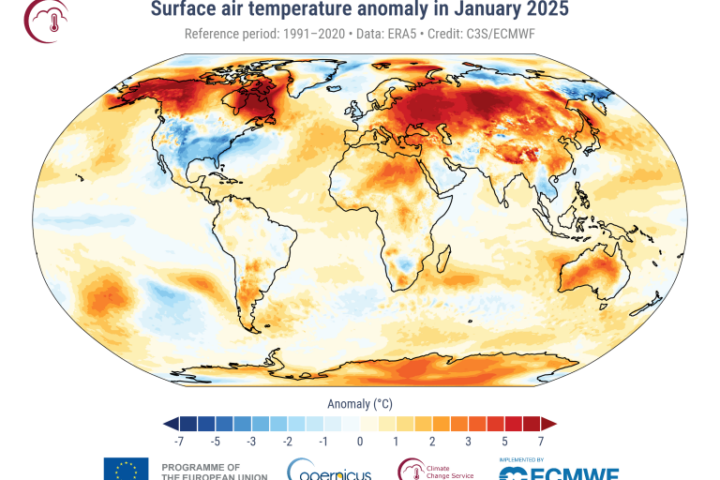

A newly discovered phenomenon affecting the sea floor of the North American continental shelves & other areas around the globe is called “bottom marine heat waves”. Australia, the Mediterranean, & the Tasmanian Seas are some of the areas that are affected by these heat waves, which are a global phenomenon. 90% of the excess heat from global warming has been absorbed by the ocean, leading to a 50% increase in surface marine heat waves in the past decade.

There is little or no evidence of warming at the surface when the bottom marine heat waves occur, & they can last longer than surface heat waves. There are devastating impacts caused by these heat waves on key species such as lobster, cod, & other commercial fish. The deaths of 1 million seabirds in 2013–2016 were the result of the severe impact on fish populations due to the “Blob” phenomenon in the Pacific Ocean. A study about the phenomenon is published in Nature journal by lead author Dillon Amaya and team.

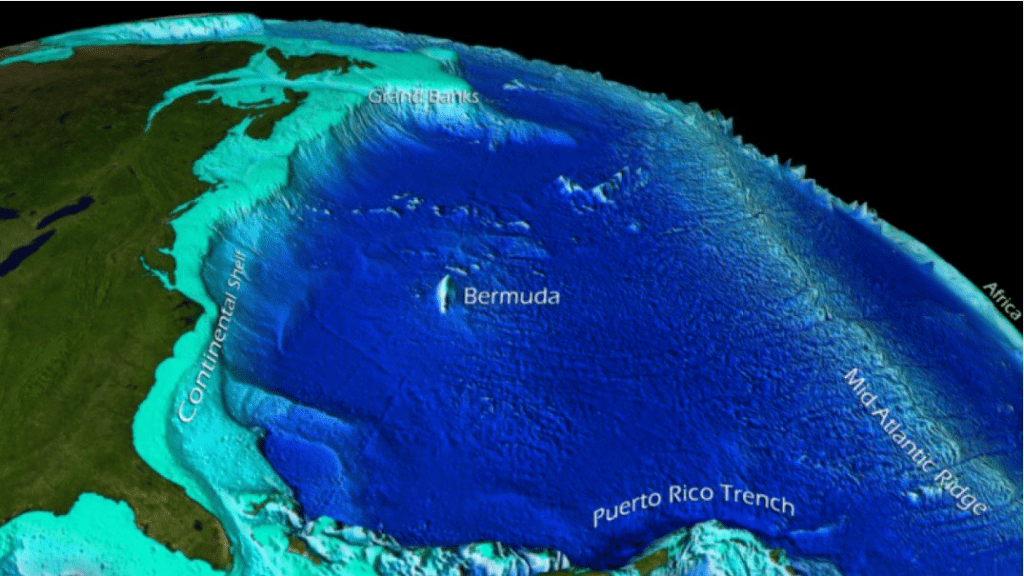

Bottom marine heat waves affect the habitats of commercial species located in the shallow depths & relative proximity to land on continental shelves. Some of the impacts caused by unusually warm bottom water temperatures are an invasive lionfish population, coral bleaching, & decline of reef fish. The frequency of marine heat waves has increased by 50% over the past ten years, & their impacts on the seafloor are not well understood.

Existing measurements used by scientists to stimulate atmospheric conditions & ocean currents to “fill in the blanks” for difficult-to-access seafloor ecosystems are quite useful.

Both the surface & the seafloor ecosystems can be affected by bottom marine heat waves simultaneously. Shallow areas where waters from different levels can intermingle experience the longest-lasting & most prevalent bottom marine heat waves.

The potential factors that could drive bottom marine heat waves are changes in ocean currents & upwelling. The bottom temperature of the water could be changed by the Gulf Stream, a warm water current on the US East Coast. Changes in surface temperature along the continental shelf on the US West Coast could be seen as changes in the rate of upwelling.