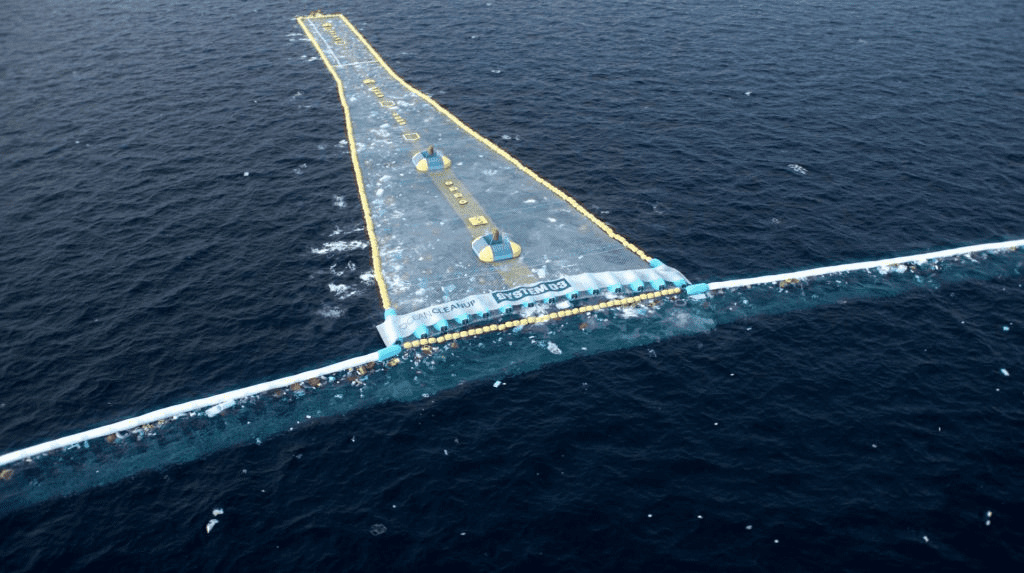

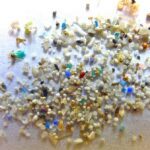

A nonprofit organization called The Ocean Cleanup is creating and expanding technology to get rid of plastic from the oceans. To accomplish this goal, they are putting efforts to clean up plastic waste that has already collected in the ocean and won’t naturally disappear even with efforts to stop the sources of plastic pollution. A new report by Laurent Lebreton, Sarah-Jeanne Royer, Axel Peytavin, Wouter Jan Strietman, Ingeborg Smeding-Zuurendonk & Matthias Egger from The Ocean cleanup and Wageningen University & Research states that 75% of plastic in great pacific garbage patch originates from fishing activities.

Findings support Ocean Cleanup’s two-pronged strategy for accomplishing this goal: reducing riverine plastic pollution and eliminating ocean legacy waste. While the bulk of plastic that ends up in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) comes from marine-based activities, the other major source of plastic that ends up in the world’s oceans comes from land-based sources.

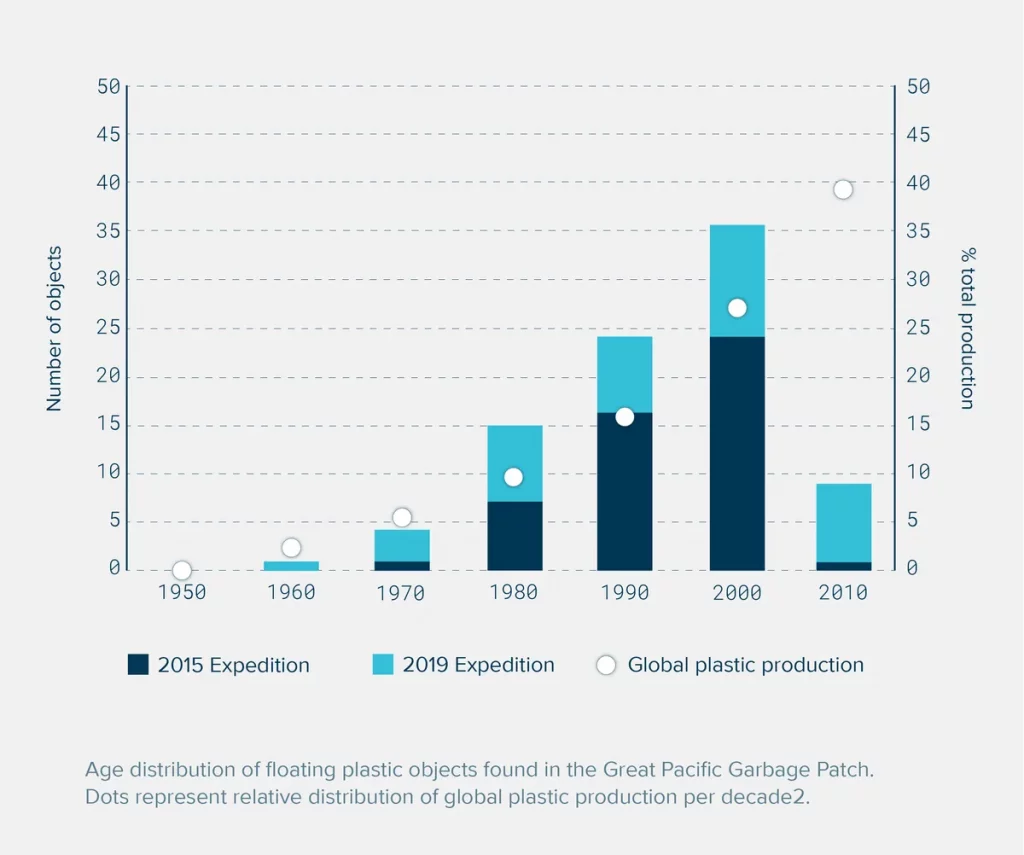

GPGP is an accumulation of plastic and other kinds of trash. Now it is a subject of study for the Ocean Cleanup to determine its composition, origins, and age. These discoveries will help improve cleaning methods and obtain knowledge about the sources of this plastic & also help understand the plastic pollution issue better .

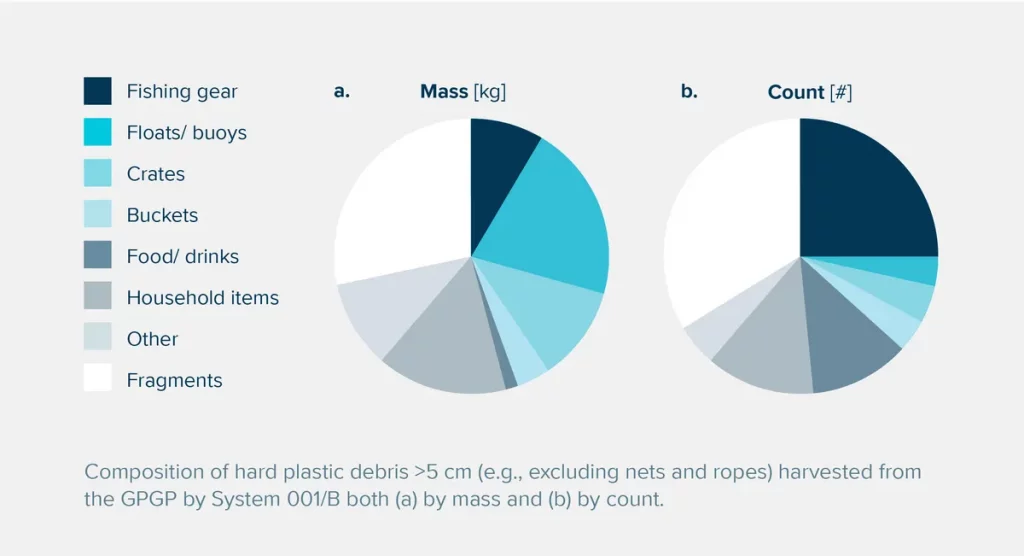

The majority of information about plastic waste at sea has been gathered using small-scale surface trawls, which were originally designed to gather plankton. These trawls frequently gather little plastic pieces because of their small size. These pieces are difficult to identify, which reduces their value in figuring out where GPGP plastic originates. As per this extensive investigation, a third of the items collected were unidentified bits. Floats, buoys, crates, buckets, baskets, containers, drums, jerry cans, fish boxes, and eel traps made up the majority of the remaining two thirds.

On the other hand, larger plastic objects occasionally conceal information that can be used to determine their age, as well as their source and place of origin. However, seagoing researchers have hardly ever collected such objects. Instead, they are primarily measured by remote sensing methods.

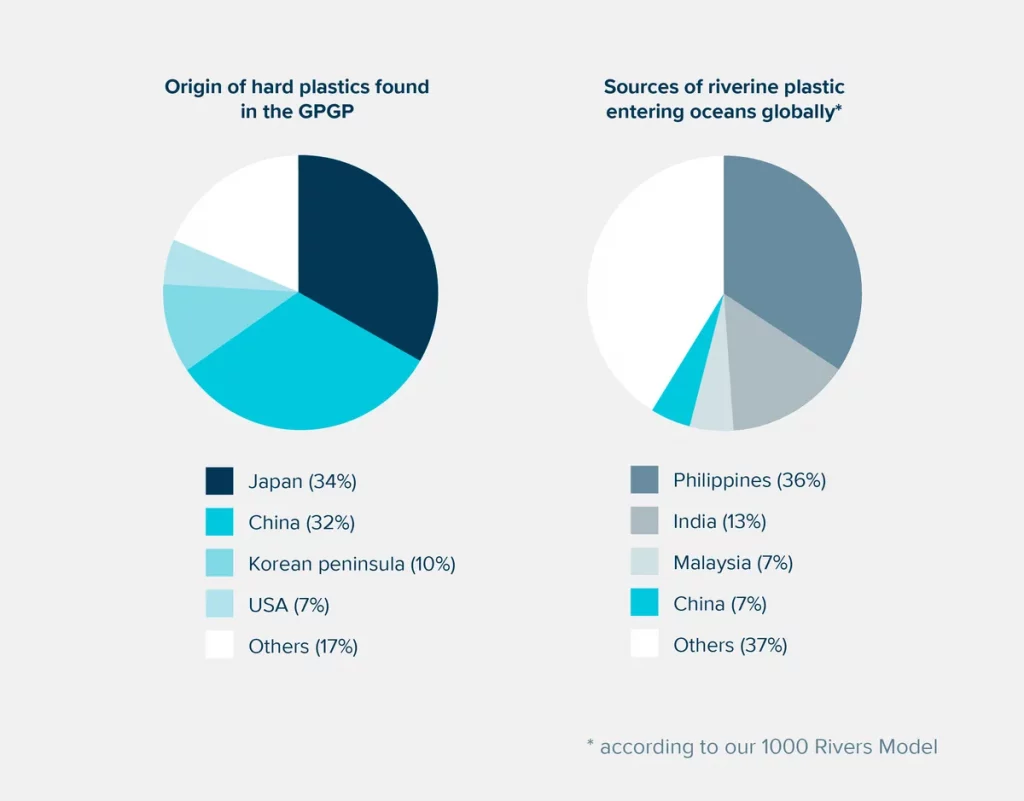

The main origins of the items were firstly listed as being from Japan (34%), China (32%), the Korean peninsula (10%), and the USA (7%). But perhaps surprisingly, other North Pacific Ocean rim nations with significant estimated riverine plastic emissions (like the Philippines) were not highly represented in the plastics gathered from the GPGP.

The researchers were puzzled by the apparent discrepancy between the abundance of plastics associated with fishing in the GPGP and the well-popularised notion of land-based plastic emissions into the ocean. Then why is the GPGP primarily filled with plastics from fishing activities, if most floating plastic in the global ocean is supposed to have originated from terrestrial sources? Simply put, the models replicate the dispersion of virtual plastic particles across the ocean surface using data on wind and currents in the ocean and the release of virtual plastic particles into the ocean (either from rivers or from fishing vessels).

These plastic dispersion models are valuable instruments for researching how floating marine debris is transported. For particles that are simulated to enter the ocean from rivers, the models record the country of origin or the flag of the fishing vessel.

According to the results of the compositional studies, the majority of virtual model particles accumulating in the GPGP were identified as coming from Japan, China, the Korean peninsula, and the United States. This offers solid proof that fishing activities at sea, and not just fishing nets themselves, are a significant fraction of the floating hard plastics in the GPGP.

The plastic situation involving the fishing source questions the prevalent fishing methods that contribute to plastic in the GPGP. Fishing activities that contributed to the model particles identified in the GPGP included 48% from trawlers while fixed gear and drifting longlines made up 18% and 14% of the total. The technique was unknown for 16% of modelled fishing operations that contributed to model particle emissions. Drifting longlines were used over the entire North Pacific Ocean’s oceanic zone, trawling and fixed gear activities contributed to the GPGP often happened close to the Asian and North American continental shelves.

In comparison to plastic waste released during fishing operations at sea, floating plastics released from rivers have a considerably higher possibility of returning to land quickly & if the plastic is released closer to the shore, it is also more likely to do so. Virtually all of the plastic debris that is dumped into rivers spends a lot of time close to the coast, with a high probability of beaching at the river mouth. In contrast to the sort of hard plastic debris found in the GPGP, which is primarily thick, positively buoyant & consists of polyethylene and polypropylene. So floating plastic items entering the oceans from rivers predominantly differ from the fishing or other marine related plastic.

Fishing activities may produce floating plastic garbage that is two to ten times more likely to enter the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) than plastics coming from rivers. This explains why rivers only make up a minor portion of the plastic that has collected in the GPGP, despite being a significantly greater supply of plastic waste than fishing activities. These results clearly have implications for cleanup plans and for people who engage in Pacific fishing activities.

To fully rid our seas of plastic, it is necessary to understand how and where plastic enters the water and what happens to it once it gets there. This information is especially important for floating plastic debris since they can travel over great distances at sea and cause a transboundary problem because the regions or countries who are most affected are frequently not the ones that are polluted in the first place. Discovering the precise entry points of plastic debris that persists in offshore waters, the location of its manufacture, and what industrial, commercial, and cultural practices are causing it to accumulate at sea are all necessary to develop effective and efficient mitigation strategies against ocean plastic pollution.