Norway inaugurated the gateway to a vast underwater carbon dioxide cemetery on Thursday, September 26th. Called Northern Lights, this project will allow CO2-emitting industries to reduce their emissions into the atmosphere. It’s the first commercial carbon capture and storage service, launching the world’s first commercial carbon transport and storage service.

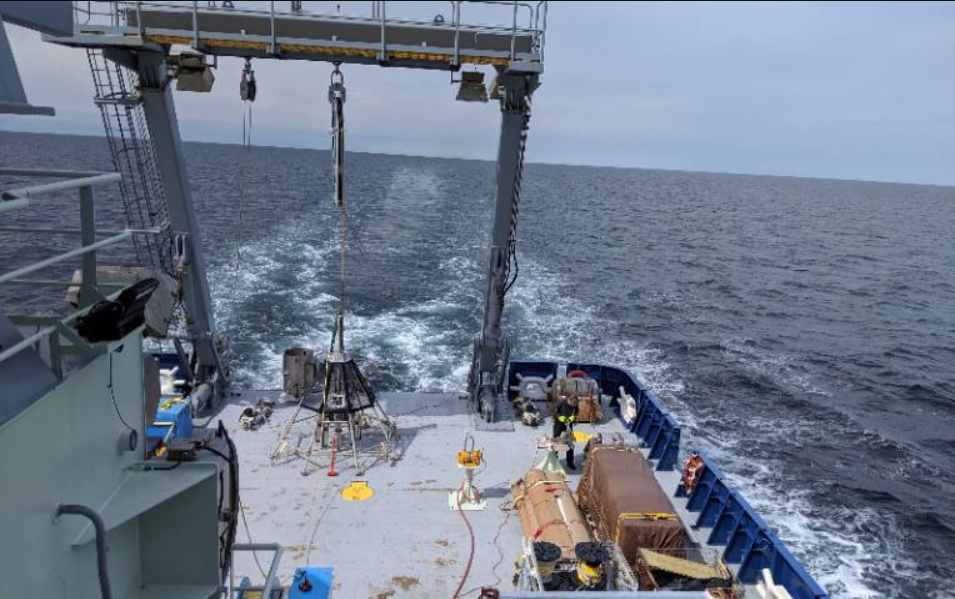

The project is located in the island municipality of Øygarden, near Bergen. It features an onshore terminal with 12 brand-new large metal tanks ready to receive CO2. A network of pipes surrounds the facility, with one modest-sized pipe diving into the North Sea. The CO2, previously liquefied, will be transported by ship and then injected 110 kilometers offshore into a saline aquifer 2,600 meters below the seabed.

Driven by oil giants Equinor, Shell, and TotalEnergies, Northern Lights should bury its first tons of CO2 in 2025. Its annual storage capacity will initially be 1.5 million tonnes, with plans to increase to 5 million tonnes if demand follows. Tim Heijn, director of Northern Lights, explains, “The whole world is looking to Norway to learn about CCS. Since construction started, we have welcomed more than 10,000 visitors from more than 50 countries. Today we celebrated the completion of the facilities together with the people of our host municipality Øygarden, the Norwegian Ministry of Energy, and key stakeholders, including policy makers and industry partners in the CCS chain.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) supports the carbon capture and storage (CCS) solution, particularly to reduce the carbon footprint of hard-to-decarbonize industries such as cement or steel. However, its development is hampered by high costs compared to the purchase of CO2 emission allowances by industrialists and largely depends on subsidies.

Currently, the total CO2 capture capacity worldwide is nearly 50 million tonnes (Mt), representing 0.1% of global annual emissions. To contain global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, CCS should prevent at least 1 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions per year by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Similar Posts

The Norwegian state has taken on 80% of the costs in the first phase of Northern Lights, although the exact amount remains confidential. Per Sandberg, Senior Advisor – Business Development at Equinor stated, “Northern Lights has changed both the regulatory and industrial thinking around CCS, as it represented a market opener for the technology and made CCS available and accessible to European users.”

The North Sea, with its depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs and extensive pipeline network, is a suitable region for CO2 burial. Several other offshore storage projects are progressing in Europe, including Greensand, developed by Ineos and 23 partners off the coast of Denmark, which plans to start in late 2025 or early 2026.

Northern Lights has already signed several cross-border contracts, notably with companies such as Yara, a fertilizer industry player, and Ørsted, a Danish energy group. These agreements provide for the storage of CO2 captured from factories in the Netherlands and Denmark, demonstrating growing industrial interest in this emissions management solution.

The development of additional contracts remains challenging due to the low cost of European emission allowances. Currently, it’s more profitable for companies to purchase these allowances rather than adopt long-term storage solutions. CCS appears as a competing option to the current strategy of industrialists, who prefer short-term solutions to manage their emissions.

The large-scale deployment of Northern Lights will largely depend on European industrialists’ ability to adopt this technology as a viable solution for their decarbonization needs. If CCS costs decrease and emission allowances become more constraining, it could become an essential lever in carbon emissions management.

Over the past two years, global investments in CCS have quintupled to $11.3 billion in 2023, according to Statista. With this project, Norway is positioning itself as a major player in managing CO2 emissions in Europe while offering an innovative solution to the most polluting industries. The challenge now lies in convincing a larger number of industrialists to adopt this technology.