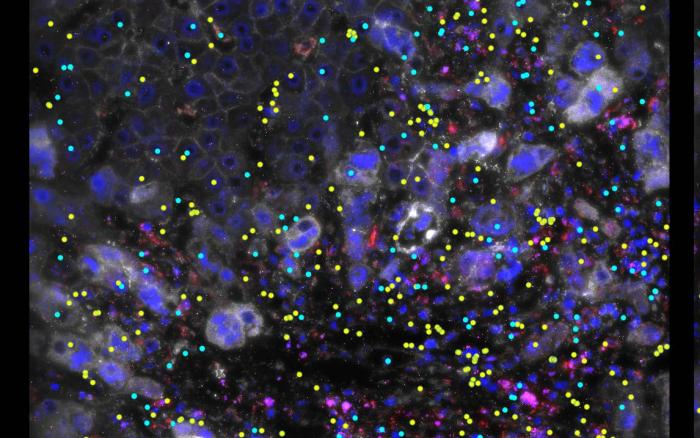

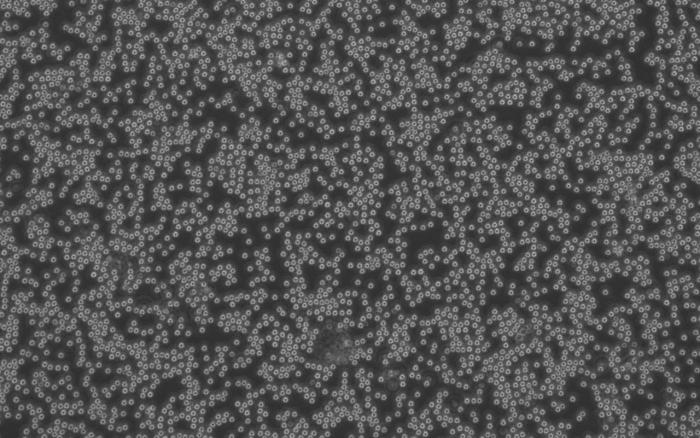

A research team from the Francis Crick Institute, University College London, and Imperial College London investigated a non-coding DNA region known as a “gene desert,” previously associated with IBD and other autoimmune diseases, and discovered the presence of an “enhancer.” An “enhancer” acts like a volume dial, capable of increasing the amount of protein produced by a gene. The enhancer discovered by the research group was only activated in macrophages, which play a significant role in inflammatory responses, and it enhanced the activity of a gene called ETS2.

Using genetic editing, the research group demonstrated that ETS2 is essential for most inflammatory responses in macrophages. Remarkably, increasing the amount of ETS2 in resting macrophages transformed them into inflammatory cells similar to those found in IBD patients. Furthermore, the research group showed that many genes previously associated with IBD are part of the ETS2 pathway, proving that the ETS2 pathway is a major cause of IBD.

As there are no drugs that specifically inhibit ETS2, the research group searched for drugs that could indirectly suppress ETS2 activation. They found that MEK inhibitors, already prescribed for other non-inflammatory diseases, were predicted to suppress the inflammatory response of ETS2. When tested, MEK inhibitors were found to reduce inflammation not only in macrophages but also in intestinal samples from IBD patients. Due to the risk of side effects on other organs, the research group is working with LifeArc, a medical research organization, to find ways to deliver MEK inhibitors directly to macrophages.

Approximately 95% of IBD patients have one or two variants of the ETS2 enhancer. The research group speculates that these variants have persisted because, before the advent of antibiotics, ETS2 played a role as a switch for infection defense, and they are particularly common in regions with high rates of infectious diseases.

James Lee, group leader of the Genetic Mechanisms of Disease Laboratory at Crick and consultant gastroenterologist at the Royal Free Hospital and UCL, who led the research, points out: “IBD usually develops in young people and can cause severe symptoms that disrupt education, relationships, family life and employment. Better treatments are urgently needed. Using genetics as a starting point, we’ve uncovered a pathway that appears to play a major role in IBD and other inflammatory diseases. Excitingly, we’ve shown that this can be targeted therapeutically, and we’re now working on how to ensure this approach is safe and effective for treating people in the future.”

Christina Stankey, a PhD student at Crick and first author along with Christophe Bourges and Lea-Maxie Haag, adds: “IBD and other autoimmune conditions are really complex, with multiple genetic and environmental risk factors, so to find one of the central pathways, and show how this can be switched off with an existing drug, is a massive step forwards.”

Similar Posts

Volunteer participants from the NIHR BioResource, with and without IBD, provided blood samples that contributed to this research. The research was funded by Crohn’s and Colitis UK, Wellcome Trust, MRC, and Cancer Research UK, and the researchers worked with collaborators across the UK and Europe.

Ruth Wakeman, Director of Services, Advocacy, and Evidence at Crohn’s & Colitis UK, states as a final idea: “Every year, more than 25,000 people are told that they have Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Crohn’s and Colitis are complex, lifelong conditions for which there is no cure, but research like this is helping us to answer some of the big questions about what causes them. The more we can understand about Inflammatory Bowel Disease, the more likely we are to be able to help patients live well with these conditions. This research is a really exciting step towards the possibility of a world free from Crohn’s and Colitis one day.”