In a series of groundbreaking studies, an international team of researchers has uncovered new evidence that paints a more complex picture of the interactions between Neanderthals and modern humans in Europe tens of thousands of years ago. The findings, published in the journals Science Advances and Cell Genomics, suggest that the Neanderthals’ isolated social structure may have contributed to their eventual disappearance around 40,000 years ago.

Alternating Occupations at Grotte Mandrin

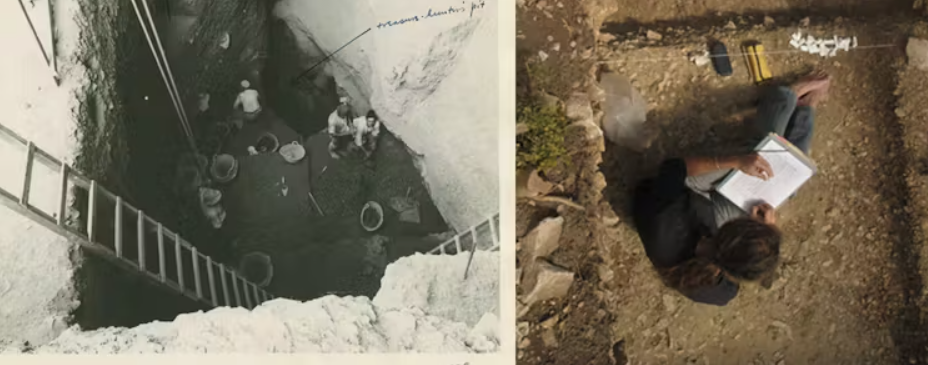

The latest discovery comes from Grotte Mandrin, a cave site in France’s Rhône Valley. Led by Dr. Ludovic Slimak of Université de Toulouse Jean Jaurès, the researchers found a fossil molar belonging to a modern human child in a layer sandwiched between layers containing Neanderthal remains. The molar, dated to around 54,000 years ago, pushes back the earliest known presence of Homo sapiens in western Europe by about 10,000 years.

“The Mandrin findings document the first clearly demonstrable alternating occupation of a site by Neanderthals and modern humans,” said study co-author Professor Chris Stringer from London’s Natural History Museum. “We’ve often thought that the arrival of modern humans in Europe led to the pretty rapid demise of Neanderthals, but this new evidence suggests that both the appearance of modern humans in Europe and disappearance of Neanderthals is much more complex than that.”

The cave has yielded dental remains from at least seven individuals across 12 archaeological layers spanning 120,000 to 42,000 years ago. Six were identified as Neanderthal, while the molar in the middle layer was distinctly modern human.

Genomic Clues to Neanderthal Society

Meanwhile, researchers from the University of Copenhagen’s Globe Institute have sequenced the genome of a Neanderthal male from remains discovered in a different French cave. By comparing it with other known Neanderthal genomes, they found that this individual came from a lineage not yet represented in the genomic record.

“The newly found Neanderthal genome is from a different lineage than the other late Neanderthals previously studied,” said Associate Professor Martin Sikora, one of the study’s authors. “This supports the notion that social organization of Neanderthals was different to early modern humans who seemed to have been more connected.”

The sequencing revealed high levels of inbreeding and low genetic diversity among Neanderthals, indicating that they lived in small, isolated groups for many generations. In contrast, early modern human populations showed evidence of greater connectivity and genetic exchange.

“We see evidence of early modern humans in Siberia forming so-called mating networks to avoid issues with inbreeding, while living in small communities, which is something we haven’t seen with Neanderthals,” noted co-author Postdoc Tharsika Vimala.

A Gradual Replacement

Dr. Slimak’s team has proposed that Homo sapiens colonized Europe in three distinct waves between 54,000 and 42,000 years ago, interacting intermittently with Neanderthals. This contrasts with the previous view of a single, rapid replacement.

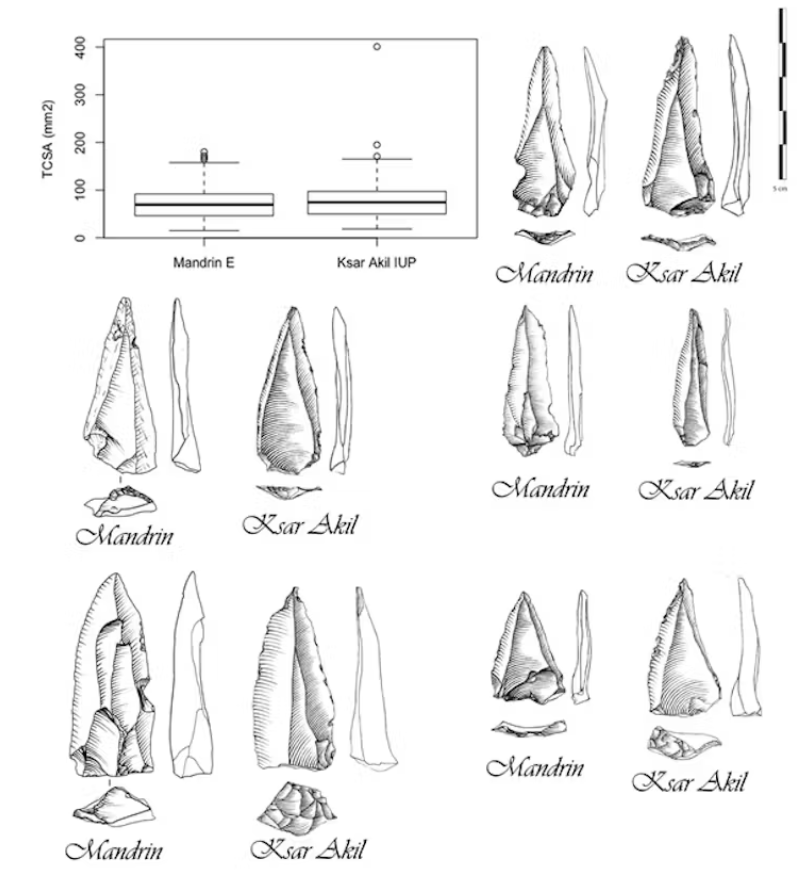

Analyzing thousands of stone tools from Grotte Mandarin and Ksar Akil in Lebanon, the researchers identified similar production methods and styles appearing at both sites during the same time periods. This led them to conclude that successive waves of modern humans brought these technologies with them from the Near East to western Europe.

“All the technical processes, all the phases of production of these points, were precisely the same in both sites, in the same chronology,” Dr. Slimak explained. “This precise community of knowledge and traditions induced that the Neronian (the tool style found at Grotte Mandrin) was in fact the archeological indication of a very early migration of Sapiens in Europe, far before expected.”

Similar Posts

Neanderthal Creativity and Mysterious Relations

While modern human tools may have been more standardized and efficient, Dr. Slimak emphasized that Neanderthals displayed a singular creativity. “If you take crafts from Homo Sapiens, for example, 100 tools or 100 flints from 50 to 100,000 years ago, the 10,000 tools or flints after will be exactly the same,” he said. “But if you take a Neanderthal tool in comparison, and then you analyze a million after that in the same layer, in the same societies, they are all completely different. Each tool is a specific creation.”

The nature of the interactions between Neanderthals and modern humans remains enigmatic. Although genomic evidence shows that all early Homo sapiens in Europe carried some Neanderthal DNA, no Neanderthal remains from the period have been found with Homo sapiens DNA.

Dr. Slimak suggested this could indicate either violent conflict, with modern humans killing Neanderthal males and incorporating the females into their groups, or a scenario of friendly relations but low biological compatibility. “I think we are dealing with interrelations between humanities that did not work out in the end,” he said.

An Evolving Understanding

While the new studies offer tantalizing insights, Dr. Slimak acknowledged that shifting long-held views on human prehistory will take time. “The structures of the Upper Paleolithic were last defined by the Abbe Breuil in 1906, and so there was no major change for 120 years,” he noted. “I’m not waiting for all researchers to say, ‘Well, it’s fantastic you changed everything.”

The discoveries at Grotte Mandarin and the genomic analysis of Neanderthals provide important pieces in the puzzle of our evolutionary past, shedding new light on the complex history of modern humans and our extinct relatives. As more evidence emerges, our understanding of this pivotal period continues to evolve, challenging long-standing assumptions and revealing a more nuanced story of the people of Europe.