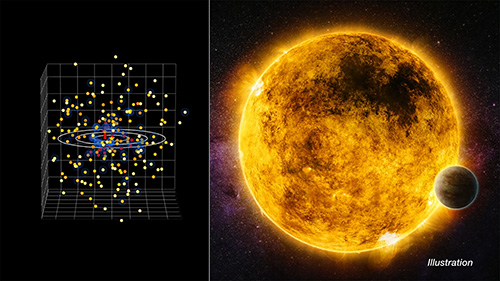

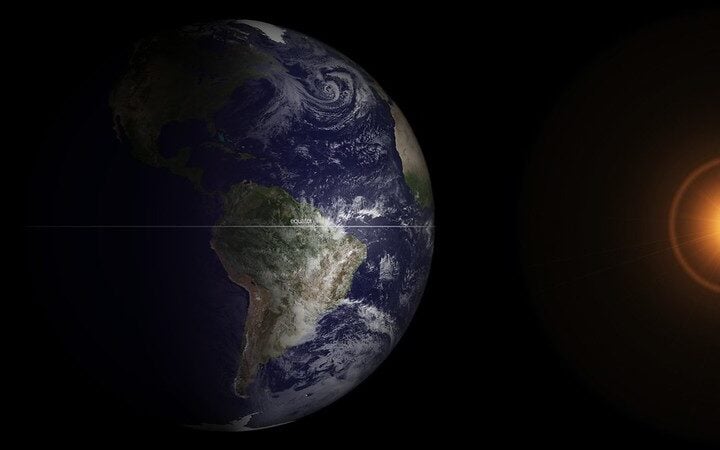

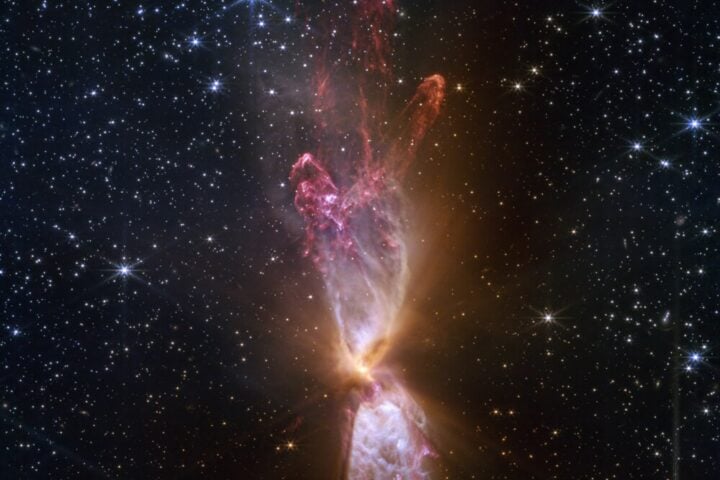

The Chandra X-ray Observatory of NASA and ESA’s XMM-Newton have observed stars that are close enough to be prime targets in the search for direct imaging of planets using future telescopes. Researchers examined stars close enough to Earth so that upcoming telescopes, operating in the next decade or two, including the Habitable Worlds Observatory in space and Extremely Large Telescopes on the ground, could image planets in the so-called habitable zones of stars. This term defines orbits where planets could have liquid water on their surfaces.

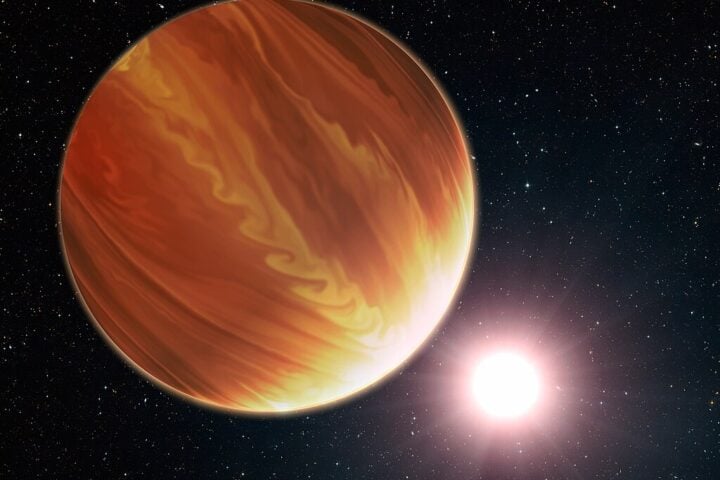

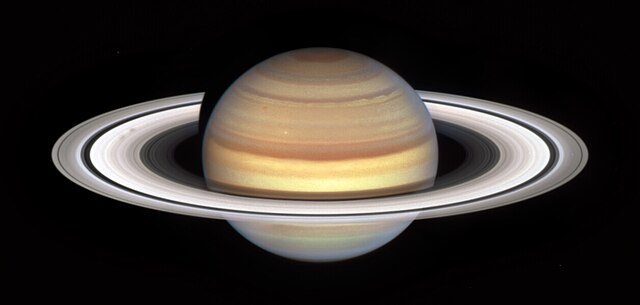

Astronomers are using these X-ray data to determine how habitable exoplanets might be, based on whether they receive lethal radiation from their orbiting stars, as described in our latest press release. This research will help guide observations with the next generation of telescopes, aiming to capture the first images of Earth-like planets. The researchers used nearly 10 days of Chandra observations and approximately 26 days of XMM observations, available in archives, to examine the X-ray behavior of 57 nearby stars, some of which have known planets. Most of these are giant planets like Jupiter, Saturn, or Neptune, while only a handful of planets or planet candidates could be less than about twice the mass of Earth.

Several factors influence what might make a planet suitable for life as we know it. One of these factors is the amount of harmful X-rays and ultraviolet light they receive, which can damage or even strip away a planet’s atmosphere. Based on X-ray observations of some of these stars using Chandra and XMM-Newton data, the research team examined which stars might have conditions conducive for life to form and thrive on their orbiting planets. They studied how bright the stars are in X-rays, how energetic the X-rays are, and how much and how rapidly they change in X-ray emission, for example, due to flares. Brighter and more energetic X-rays can cause more harm to the atmospheres of orbiting planets.

Similar Post

“Without characterizing X-rays from its host star, we would be missing a key element on whether a planet is truly habitable or not,” said Breanna Binder of California State Polytechnic University in Pomona who led the study. “We need to look at what kind of X-ray doses these planets are receiving,” she explained. “We have identified stars where the habitable zone’s X-ray radiation environment is similar to or even milder than the one in which Earth evolved,” elaborated Sarah Peacock, a co-author of the study from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “Such conditions may play a key role in sustaining a rich atmosphere like the one found on Earth.”

The study underscores the critical influence of the host star on both the evolution of its planets and the effectiveness of observational methods. It distinguishes between stars more massive than 2.5 times the mass of the Sun, which live less than 1 billion years and may make it difficult to detect planets, and smaller stars like M dwarfs, which dominate the stellar population and offer potentially longer-lived, habitable conditions. The research community remains divided on whether to focus on stars like our Sun or M dwarfs for searching for potentially habitable exoplanets, each offering distinct advantages and challenges due to factors like stellar activity and longevity. Overall, the study highlights ongoing efforts to understand the diversity of planetary systems and the potential habitability of exoplanets, paving the way for future telescopic missions to explore these questions further.

“We don’t know how many planets similar to Earth will be discovered in images with the next generation of telescopes, but we do know that observing time on them will be precious and extremely difficult to obtain,” said co-author Edward Schwieterman of the University of California at Riverside. “These X-ray data are helping to refine and prioritize the list of targets and may allow the first image of a planet similar to Earth to be obtained more quickly,” he concluded.