Mount Fuji (富士山, Fujisan) remains without snow as of November 4, 2024 – the latest snowless date since record-keeping began in 1894. The 3,776-meter stratovolcano typically receives its first snowfall (初冠雪, hatsukansetsu) by October 2, according to the Japan Meteorological Agency (気象庁, Kishōchō).

The delay breaks previous records from 1955 and 2016, when snow arrived on October 26. Shinichi Yanagi from the Kofu Local Meteorological Office attributes this to persistent high temperatures and rainfall patterns. Japan experienced its warmest summer since 1898, with June-August temperatures averaging 1.76°C above normal levels, surpassing 2010’s record of 1.08°C.

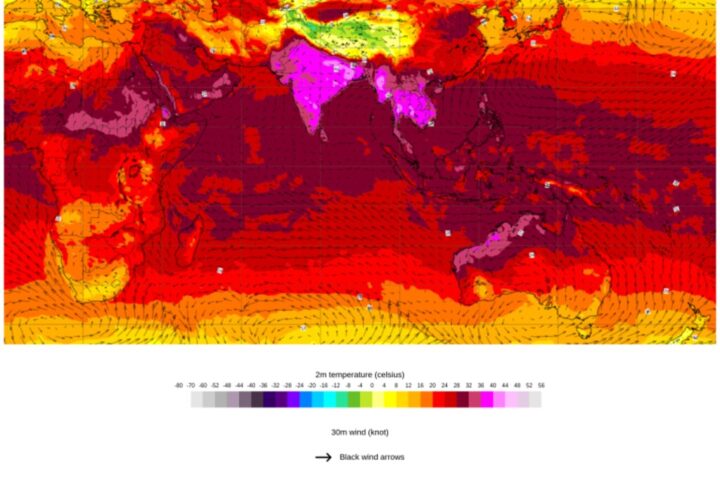

The climate system influencing Mount Fuji shows clear signs of climate change. The subtropical jet stream (亜熱帯ジェット気流, anettai jetto kiryū) maintained an unusually northern position through September, allowing warm southerly winds to dominate. Analysis from Climate Central indicates the October heat was tripled in likelihood due to climate change.

Regional impacts extend beyond tourism. The snowpack deficit affects local water resources (水資源, mizushigen) and seasonal agricultural patterns in Yamanashi and Shizuoka prefectures. Traditional markers of seasonal change like first snow (初雪, hatsuyuki) are shifting, disrupting both ecological systems and cultural practices.

Temperature data shows 74 cities recorded temperatures exceeding 30°C in early October. The Japan Meteorological Agency’s automated weather station at Fuji’s summit (富士山特別地域気象観測所) recorded sustained above-freezing temperatures through October, preventing snow accumulation despite adequate precipitation.

Similar Posts

Studies indicate these patterns align with broader Northern Hemisphere trends, where snowpack has declined across 40 years of satellite observations. The research suggests a significant decrease in early-season snow cover since the 1980s across Japan’s high-altitude regions.

Local adaptation measures include the new climbing fee (入山料, nyūsanryō) of 2,000 yen and daily visitor caps of 4,000 climbers. These measures aim to balance tourism impact with environmental preservation, particularly during the snow-free climbing season from July through September.

Current meteorological conditions, monitored through the AMeDAS (Automated Meteorological Data Acquisition System) network, suggest the delayed snowfall pattern may persist as regional temperatures remain above historical averages. Climate models project this trend could become more common, with potential impacts on Japan’s broader snowfall patterns (降雪パターン, kōsetsu patān, snowfall patterns).

The UNESCO World Heritage site’s changing conditions reflect wider climate trends across Japan’s mountain ranges, where average winter temperatures have risen 1.2°C since 1898. This mirrors global patterns, as 2024 tracks toward becoming the warmest year in recorded history.