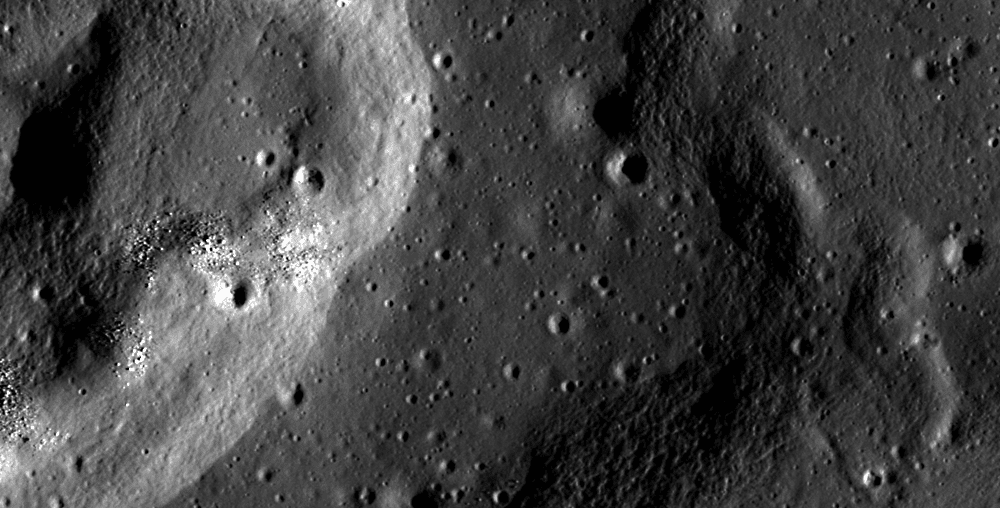

Every day, as the sun rises and sets on the lunar horizon, the moon’s surface experiences subtle tremors, known as “moonquakes.” But not all moonquakes are created equal, and some have origins that might surprise you.

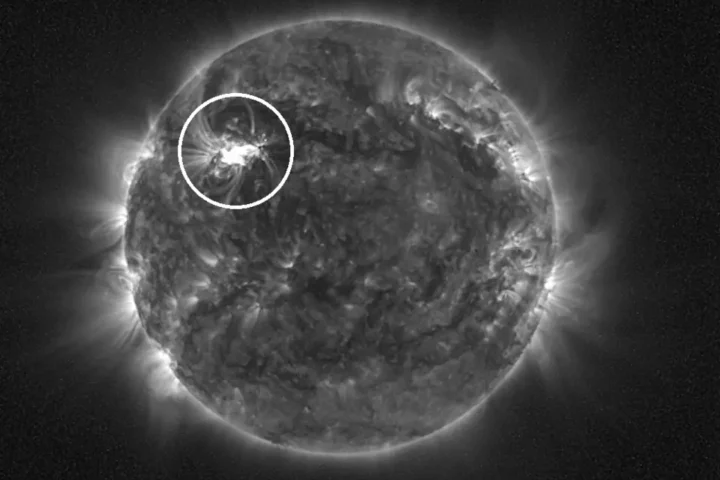

A recent study from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) delved into the nature of these moonquakes, revealing some unexpected findings. The moon, devoid of an atmosphere, undergoes extreme temperature fluctuations. During the lunar day, temperatures can soar to 250°F, plummeting to a chilling -208°F at night. This dramatic temperature swing causes the moon’s surface to expand and contract, leading to the phenomenon of thermal moonquakes.

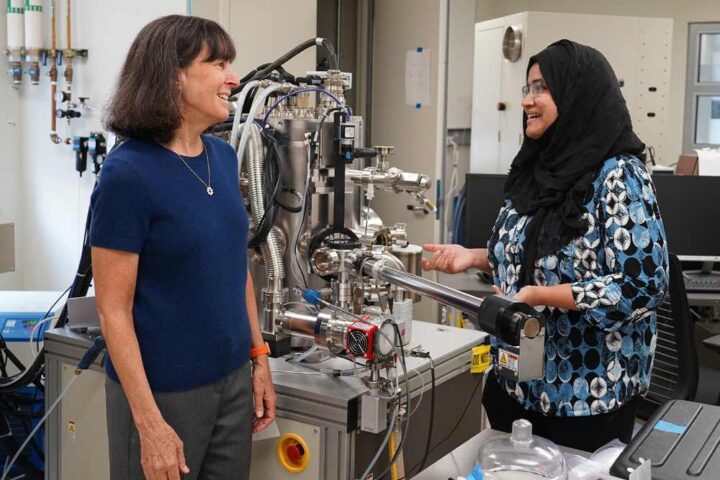

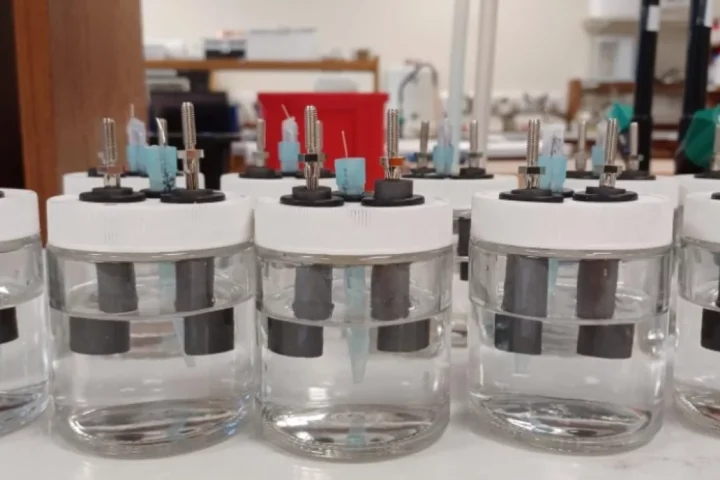

Back in the 1970s, astronauts from the Apollo 17 mission equipped the moon with three seismometers. These devices recorded thermal moonquakes for eight months, from October 1976 to May 1977. For decades, this data sat largely untouched. However, with the advent of modern techniques like machine learning, researchers have revisited this treasure trove of information.

Francesco Civilini, a recent postdoc from Caltech, spearheaded the research. The findings? Thermal moonquakes occur with clock-like precision every afternoon, as the sun descends from its zenith and the lunar surface begins its cooldown. But there was a twist. The machine-learning model detected additional seismic activity in the mornings, distinct from the evening moonquakes.

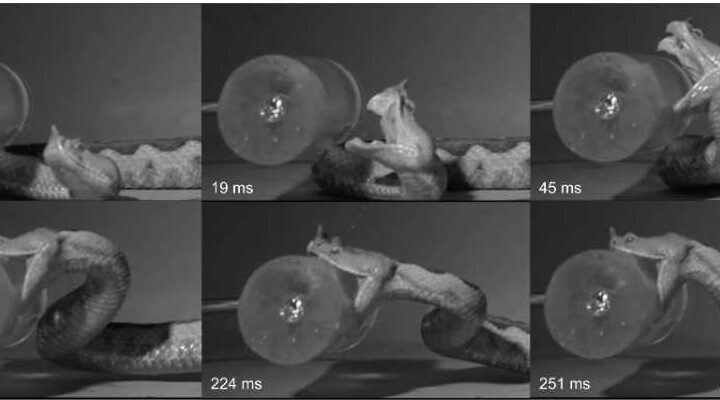

Upon closer inspection, the source of these morning tremors was astonishing. They originated not from natural lunar processes but from the Apollo 17 lunar lander base, located a mere few hundred meters away. As the lander heated and expanded with the morning sun, its creaking vibrations were picked up by the seismometers. “Every lunar morning when the sun hits the lander, it starts popping off,” remarked Allen Husker, research professor of geophysics and co-author of the study. “Every five to six minutes another one, over a period of five to seven Earth hours. They were incredibly regular and repeating.”

Similar Posts

Understanding these lunar activities is paramount, especially as NASA plans to send astronauts back to the moon with the Artemis missions. While thermal moonquakes might be too subtle for a human to feel, they provide invaluable insights into the thermal dynamics that future lunar equipment and landers must be prepared for. Husker speculates that other Apollo mission landers might also exhibit similar creaking and expansion behaviors.

But why stop at the surface? Both Earth and moonquakes offer a window into the subterranean world. Seismic waves traverse different materials at varying speeds. By analyzing these seismic signatures, researchers can deduce the materials lying beneath the surface. “We will hopefully be able to map out the subsurface cratering and look for deposits,” Husker elaborates. Some craters at the Moon’s South Pole are in perpetual shadow, never kissed by sunlight. By placing seismometers in these regions, scientists could potentially detect trapped water ice in the subsurface, as seismic waves travel slower through water.

Another study, titled “Thermal Moonquake Characterization and Cataloging Using Frequency‐Based Algorithms and Stochastic Gradient Descent,” further explored the nature of these moonquakes. It was found that there are two primary types of thermal moonquakes. The first type, impulsive and high-amplitude, is caused by the lunar module descent vehicle. The second type, emergent events, are natural reactions to sunlight, with their duration directly linked to the regolith’s temperature.

In essence, the moon continues to be a source of wonder and mystery. As we prepare for future lunar missions, understanding its seismic activities becomes crucial. The moon might not have the dramatic tectonic activities of Earth, but its subtle tremors hold secrets waiting to be unraveled. As Husker aptly puts it, “It’s important to know as much as we can from the existing data so we can design experiments and missions to answer the right questions.” The moon’s silent quakes are whispering, and we’re just beginning to tune in.