In the realm of lung cancer detection, a novel technology from MIT is making waves, not with grandiose claims, but with its practical, life-saving potential. This tech, based on inhalable nanoparticle sensors, could drastically simplify the process of diagnosing lung cancer – think inhaling nanoparticles and then taking a urine test. Simple, right?

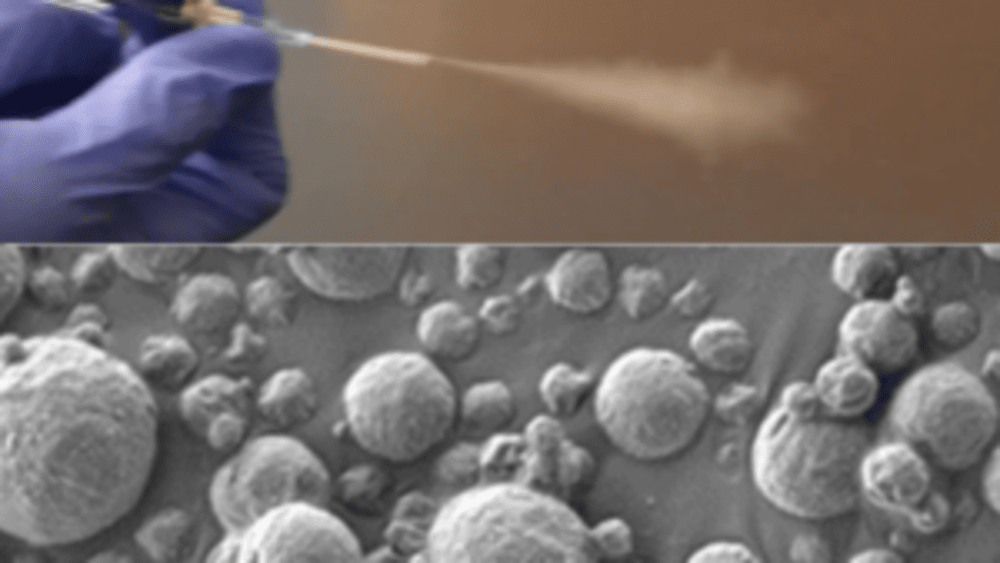

At the heart of this innovation lies a type of nanosensor, deliverable via an inhaler or a nebulizer. When these sensors encounter specific proteins linked to lung cancer in the lungs, they trigger a signal. This signal eventually finds its way into the urine, where it’s detectable via a straightforward paper test strip. The beauty of this method is its simplicity and accessibility, especially in low- and middle-income countries where CT scanners are not commonly available.

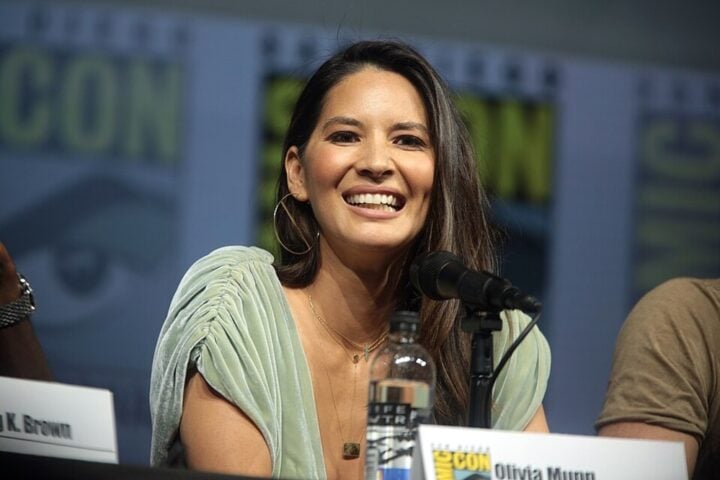

Sangeeta Bhatia, the John and Dorothy Wilson Professor at MIT, emphasizes the growing prevalence of lung cancer globally, particularly in areas plagued by pollution and smoking. Her team’s work focuses on leveraging this technology to make a tangible impact in such regions.

Around the world, cancer is going to become more and more prevalent in low- and middle-income countries. The epidemiology of lung cancer globally is that it’s driven by pollution and smoking, so we know that those are settings where accessibility to this kind of technology could have a big impact.

Sangeeta Bhatia, the John and Dorothy Wilson Professor of Health Sciences and Technology and of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT, and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science.

The approach is quite a leap from the current standard – low-dose computed tomography (CT). Bhatia’s team has spent a decade honing these nanosensors, initially designed for intravenous delivery for other cancers. For lung cancer, however, an inhalable version could be a game-changer, particularly in resource-limited settings.

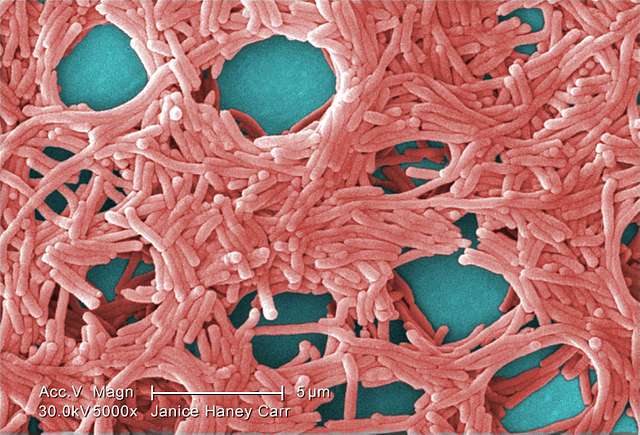

The science behind it hinges on polymer nanoparticles coated with a reporter, like a DNA barcode, that detaches when encountering tumor-related proteases – enzymes that are often hyperactive in cancerous tissues. These reporters then accumulate in the urine, exiting the body and ready for detection.

Similar Posts

This isn’t just theoretical. The team has tested their system in mice genetically programmed to develop lung tumors akin to human ones. They found that a combination of just four sensors out of twenty tested could accurately detect early-stage lung tumors. While more sensors might be needed for human application, the premise stands robust.

“When we developed this technology, our goal was to provide a method that can detect cancer with high specificity and sensitivity, and also lower the threshold for accessibility, so that hopefully we can improve the resource disparity and inequity in early detection of lung cancer.

Qian Zhong, MIT research scientist and lead author

The lateral flow assay developed by the researchers is another stroke of genius. It allows for the detection of up to four different DNA barcodes on a paper strip, requiring no pre-treatment of the urine sample. The results are available in about 20 minutes – efficiency at its finest.

Let’s not forget the real-world implications here. In places where CT scans are a distant dream, this technology could revolutionize lung cancer screening. It’s about getting answers quickly and potentially guiding patients toward life-saving treatments earlier.

Bhatia’s vision extends to human trials, with a nod to a similar sensor by her lab already in phase 1 trials for liver cancer and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) detection. The potential here is immense, not just for lung cancer but possibly for chronic pulmonary disorders and infections.

The PATROL platform, as it’s known, demonstrates a unique fusion of advanced technology and practical application. It’s a testament to how scientific innovation, when thoughtfully directed, can bridge gaps in global health care. This isn’t just a scientific triumph; it’s a beacon of hope for early cancer detection in under-resourced parts of the world.