Researchers at the NIOZ (Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research), among others, have discovered that a marine fungus can break down polyethylene, the plastic found at the bottom of the sea, as long as it has been exposed to ultraviolet radiation from sunlight. They published their findings in the scientific journal Science of the Total Environment.

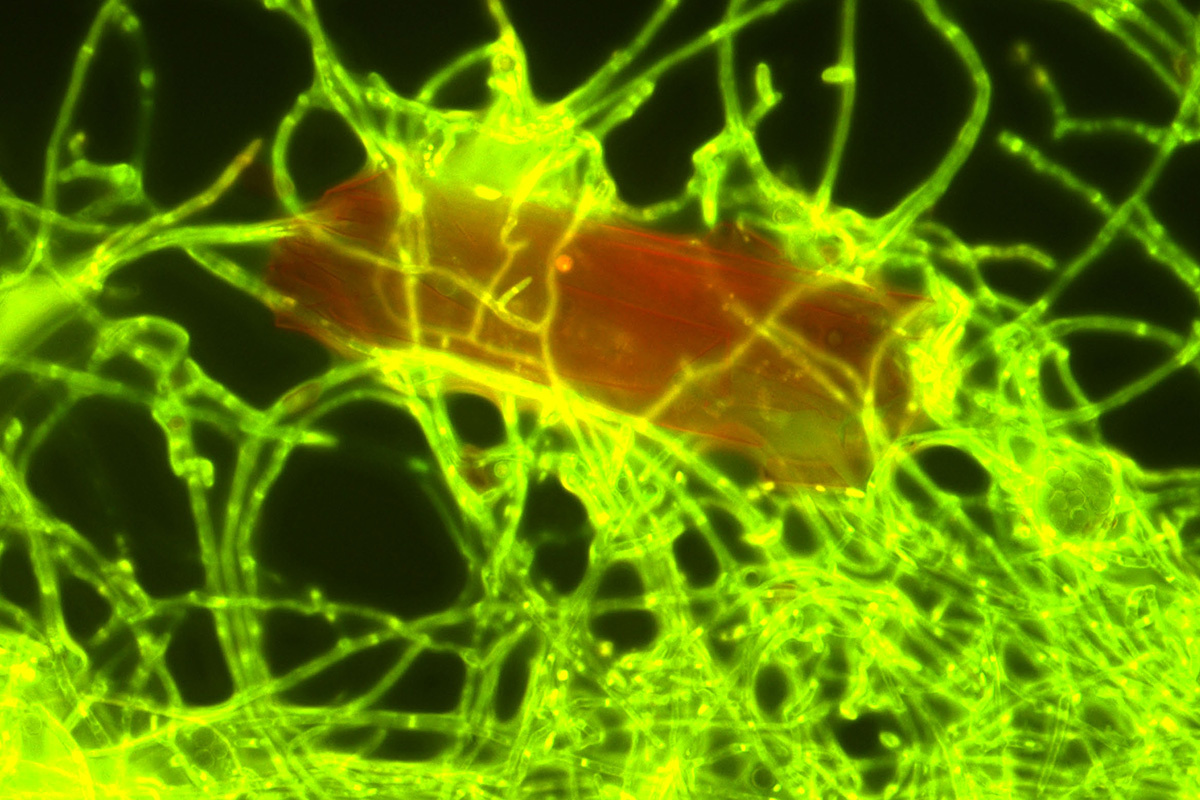

In this regard, marine microbiologists from the NIOZ discovered that the fungus Parengyodontium album can decompose polyethylene (PE) particles, the most abundant plastic in the ocean. This discovery adds the fungus to a very short list of marine fungi capable of degrading plastic, of which only four species have been identified so far.

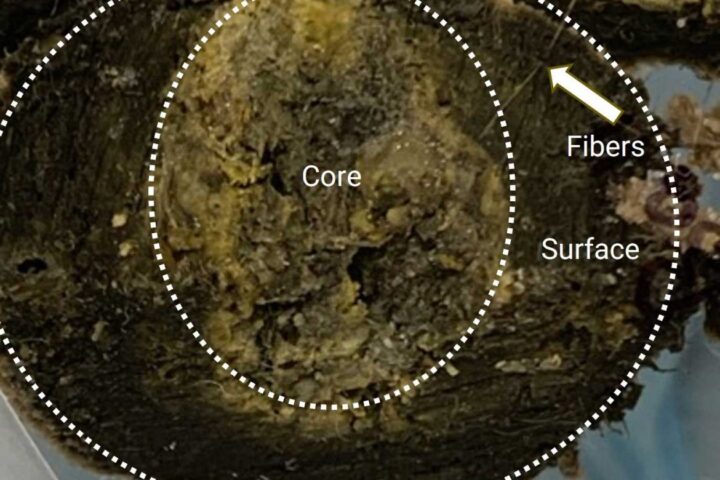

The researchers sought plastic-degrading microbes at critical points of plastic pollution in the North Pacific Ocean. They isolated the marine fungus from the collected plastic waste and cultivated it in the laboratory using special plastics containing marked carbon. Annika Vaksmaa, lead author of the NIOZ study, explained in a statement: “These so-called 13C isotopes remain traceable in the food chain. It is like a tag that enables us to follow where the carbon goes. We can then trace it in the degradation products.”

In the laboratory, Vaksmaa and her team observed that P. album breaks down polyethylene (PE) at a rate of approximately 0.05 percent per day. Vaksmaa said “Our measurements also revealed that the fungus does not utilize much of the carbon from the PE during its decomposition. Most of the PE that P. album breaks down is converted into carbon dioxide, which the fungus excretes again.” Although CO2 is a greenhouse gas, this process does not pose a new problem: the amount of CO2 released by the fungi is equivalent to that released by humans when breathing.

Similar Posts

The presence of sunlight is essential for the fungus to use PE as an energy source, as researchers have discovered. “In the lab, P. album only breaks down PE that has been exposed to UV-light at least for a short period of time. That means that in the ocean, the fungus can only degrade plastic that has been floating near the surface initially,” explained Vaksmaa. “It was already known that UV-light breaks down plastic by itself mechanically, but our results show that it also facilitates the biological plastic breakdown by marine fungi,” she added.

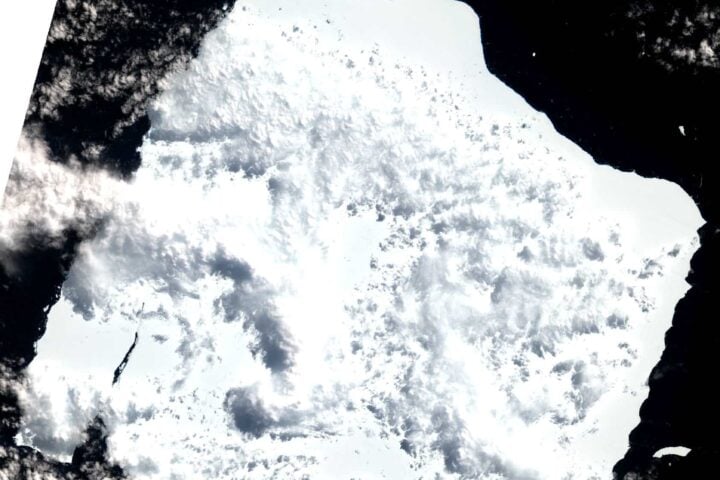

As a large amount of different plastics sink to deeper layers before being exposed to sunlight, P. album will not be able to decompose all of them. Vaksmaa hopes that there are other, as yet unknown, fungi that also degrade plastic in deeper parts of the ocean. “Marine fungi can break down complex carbon-based materials. There are a large number of marine fungi, so it is likely that, in addition to the four species identified so far, other species also contribute to plastic degradation.” There are still many questions about the dynamics of plastic degradation in deeper layers,” noted Vaksmaa.

It is urgent to find organisms that degrade plastic. Every year, humans produce over 400 billion kilograms of plastic, and this figure is expected to triple by 2060. Much of the plastic waste ends up in the sea: from the poles to the tropics, it floats in surface waters, reaches greater depths in the ocean, and eventually falls to the seabed.

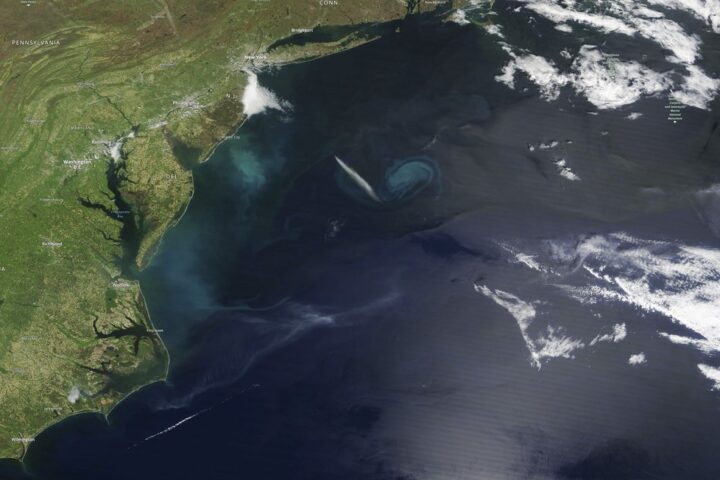

“Large amounts of plastics end up in subtropical gyres, ring-shaped currents in oceans in which seawater is almost stationary. That means once the plastic has been carried there, it gets trapped there. Some 80 million kilograms of floating plastic have already accumulated in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre in the Pacific Ocean alone, which is only one of the six large gyres worldwide,” concluded Vaksmaa.