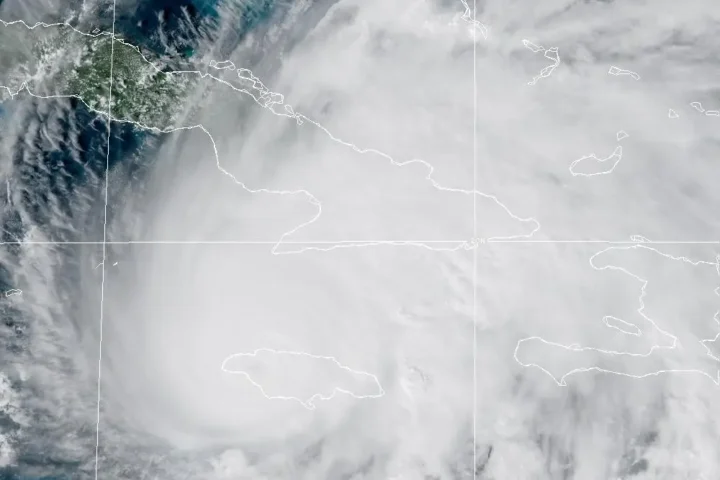

Endangered North Pacific loggerhead sea turtles are moving north at an unprecedented rate to survive warming oceans, according to new Stanford University research. The study reveals these marine reptiles are shifting their feeding grounds northward by 200 kilometers (125 miles) every decade – six times faster than typical marine species movement.

“Changes to the ocean are happening faster than expected,” says Dana Briscoe, lead data scientist at Stanford Doerr School for Sustainability. “Animals are moving farther north at a rate faster than anticipated to be able to synchronize with favorable habitats.”

The research team analyzed 27 years of data tracking turtle movements, ocean temperatures, and food availability in the Eastern North Pacific. Their findings show surface temperatures in turtle feeding areas rose by 1.6 degrees Celsius between 1997 and 2024. This warming coincided with more frequent and intense marine heat waves in the past decade.

The impact extends beyond temperature changes. Chlorophyll levels – an indicator of food availability – dropped 19% in the turtles’ feeding grounds. “The buffet has less food in it than it used to,” notes Larry Crowder, study co-author and Stanford professor.

Similar Posts:

This rapid northern shift brings new dangers. As turtles follow their food supply north, they face increased risks of fishing gear entanglement. They also risk exposure to cold currents that can leave them “cold-stunned” – too weak to swim. Last year, loggerhead turtles washed ashore on Oregon beaches in record numbers.

The North Pacific Transition Zone, where these turtles feed, serves as what Crowder calls “the buffet line for the North Pacific.” This area teems with life at the boundary between subarctic and subtropical waters, providing food for young turtles migrating from Japanese coastal waters.

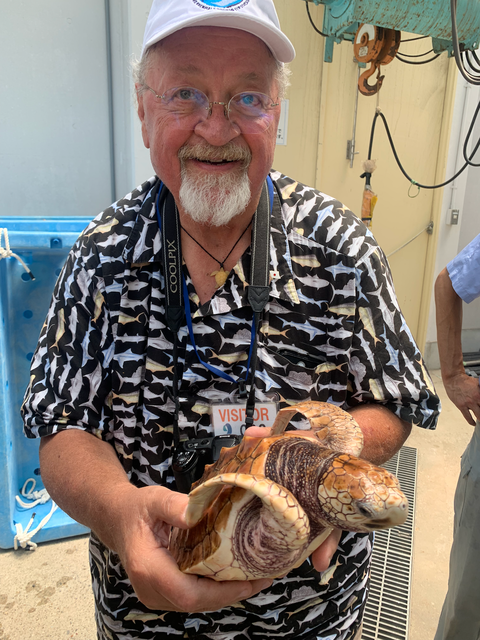

To continue studying these changes, researchers launched the Loggerhead STRETCH project. In July, they will release 25 more satellite-tagged turtles, marking the project’s third group. These turtles act as ocean observers, helping scientists understand migration patterns and ocean current changes.

“In a lot of ways, the animals are the oceanographers, and we’re the ones that are learning from them,” Briscoe explains.

The Stanford team’s findings highlight how climate change forces marine species to adapt rapidly, with potentially risky consequences. While loggerheads currently keep pace with these changes, their shifting range signals broader disruptions in marine ecosystems that could affect various species sharing these waters, including seabirds, marine mammals, and sharks.