- Appeals Court sets aside landmark judgment favoring indigenous community reclaiming ancestral lands in the Peruvian Amazon, sparking controversy and criticism from legal experts.

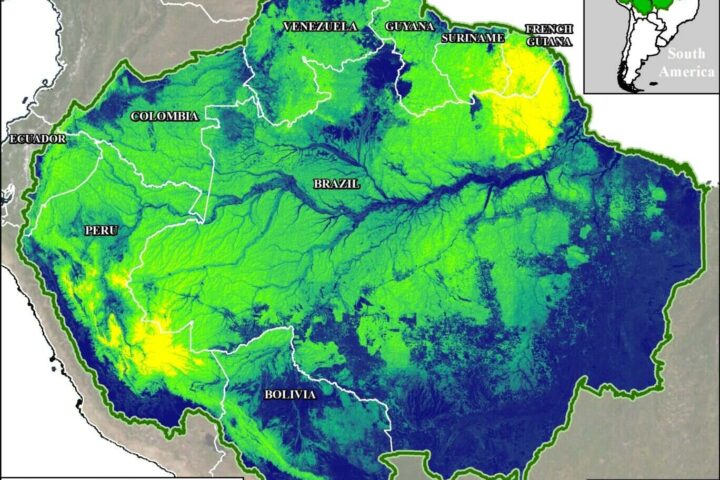

- Kichwa Natives argue that the construction of Cordillera Azul National Park involved land theft, leading to poverty and loss of access to natural resources, while major companies invest in carbon credits from the park.

- Despite initial ruling in favor of the Kichwa community, the judgment is overturned due to procedural errors, raising concerns about the protection of indigenous rights and the fairness of the legal process.

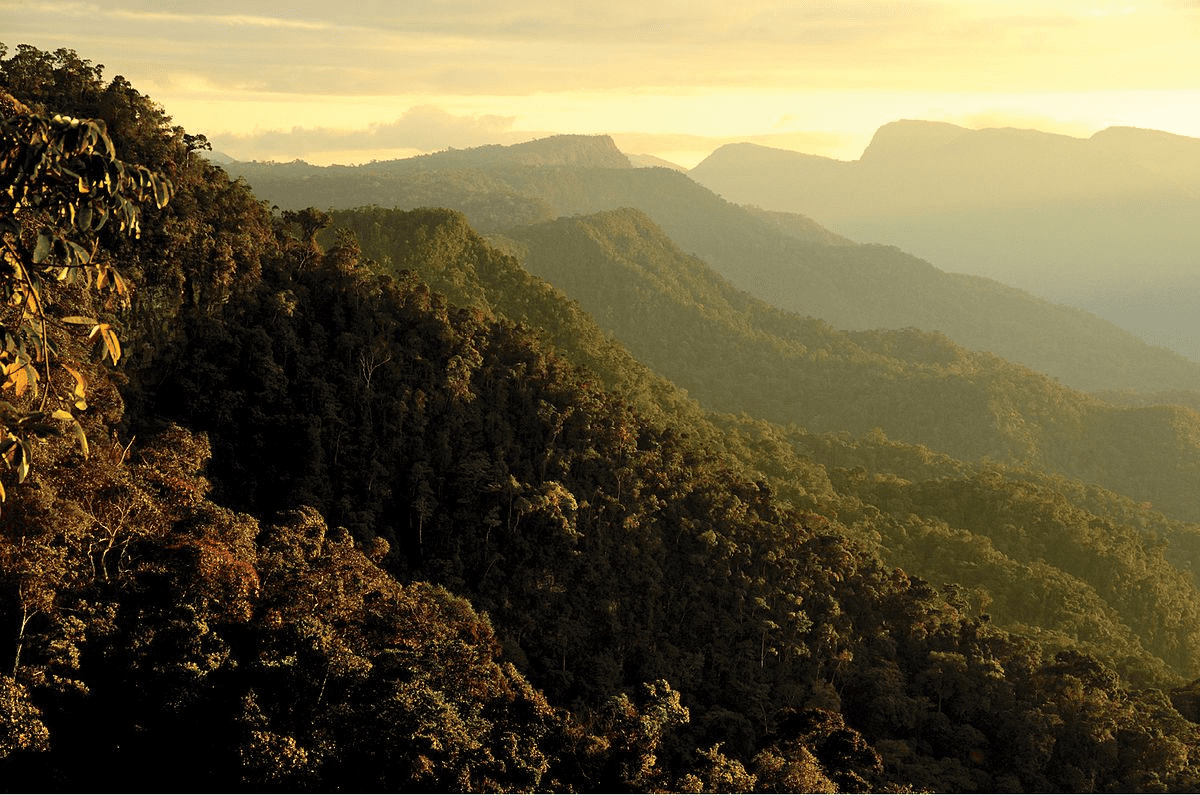

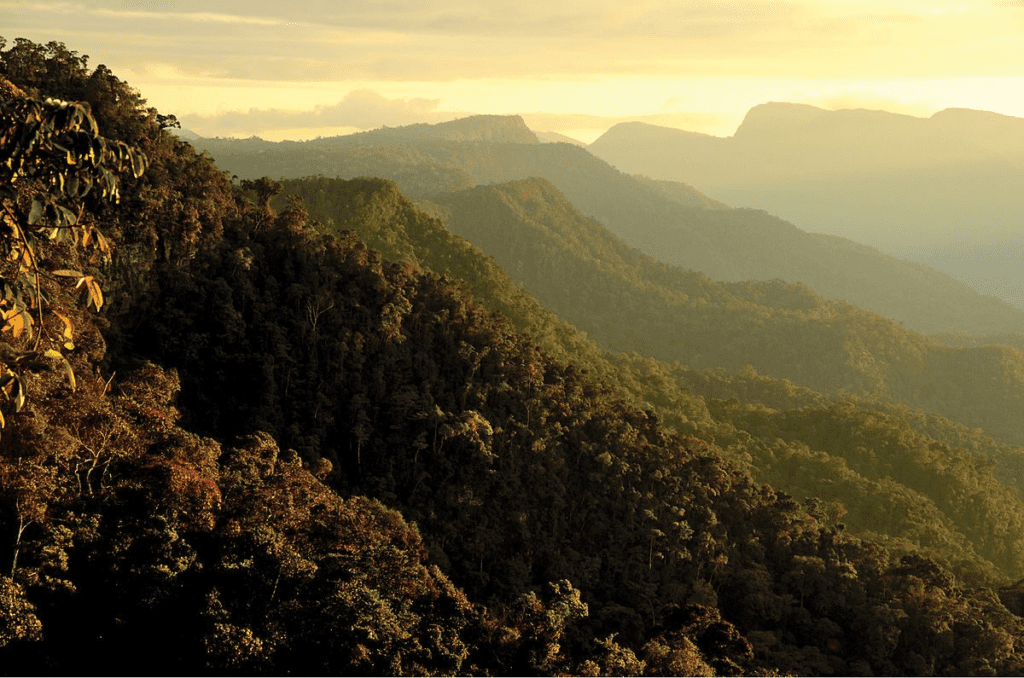

A landmark judgment that allowed the indigenous community in the Peruvian Amazon to reclaim their ancestral lands has been set aside by the Appeals Court. The indigenous tribes are the Kichwa Tribes that lived where the Cordillera Azul National Park prevailed before the park was founded in 2001. Many lawyers and legal experts have found the Appeals Court judgment unethical.

The Kichwa Natives state that the park’s construction involves the theft of their land. Many major companies, like Shell and TotalEnergies, have spent over $80 million in buying credits in the park to balance their carbon emissions. As a result of these financial investments, the natives suffered from poverty due to the loss of access to natural resources in the park area. A petition was brought forth by the Puerto Franco community members of Kichwa in April to recognize their human rights violations. Judge Simona del Socorro Torres Sánchez ruled in favor of the community upholding that the construction of the park amounted to a violation of their basic constitutional rights. The judge directed the authorities to grant the natives the title to land and involve them in conservation activities and park management. The judgment was overruled after ten days by the Appeals Court, justifying the decision with procedural irregularities and defects in the judgment.

Plea of the Natives:

The petition brought forth by the native community, being the aggrieved party, asked for basic recognition of their rights as residents of the land. Their plea was to get access to the natural resources of the park. Also, their plea included compliance by the authorities with the rights of their communities over the area where the park overlaps their land. The plea also contained their participation in the management and decision-making regarding the park. The resizing of the native land to exclude the territory occupied by the community was also included as one of the issues.

The plea was brought forth on the grounds of their ancient settlement on the land over which the park was constructed. It was a forceful acquisition that denied them access to natural resources and land, leading to economic issues and ill health. It was highlighted that the settlement of the community in the Valley of Pikiyacu Alto Biavo, which is decades old, dates back to the 16th century. However, in 2011, the Supreme Court of Peru approved the order to construct the Cordillera Azul National Park without consulting the members of the communities. This restricted access to several natural resources, which prevented the natives from sustaining themselves.

Similar Post

Events post-judgment:

The previous judgment was passed in favor of the natives, marking a milestone in protecting tribal rights. The ruling ordered park rangers to grant the Kichwa access to the entire forest and suggested they should benefit from carbon credit sales. However, ten days later, the judgment was overruled by the Appeals Court, noting that CIMA, a non-profit organization overseeing the carbon credit project and running the park on the Government’s behalf, had been wrongfully added as a co-defendant in the petition. Therefore, this was considered a procedural error, and the judgment was overruled.

Backlash over the judgment

Legal experts opined that it was irregular of the court to dismiss the entire petition. CIMA welcomed the ruling, emphasizing the need to follow formal procedures in judicial processes. Three Peruvian lawyers commented upon the ruling of the Appellate Court, of which two duly noted that even though adding CIMA as a defendant can amount to a procedural error, it cannot amount to a violation of the procedure in itself. Pedro Grandez, a constitutional lawyer and a professor based out of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, stated that the judgment is an anomaly. He is of the opinion that the courts have observed the procedural aspect, pointing out and basing the judgment on procedural errors rather than adjudicating upon the substance or subject matter of the dispute. The Peruvian Government highlights that the Kichwa Natives have exhausted their statute of limitations to make claims regarding the overlapping of the Kichwa Territory due to the undefined legal status.

Current Situation

Peruvian authorities stated that the community did not object to the park’s creation in 2001 or raise complaints during its inception. However, an investigation by the Associated Press in December revealed that the park likely includes Kichwa’s ancestral territory based on an Indigenous Convention signed by Peru in 1994. Kichwa members actively describe losing access to the land, including their inability to clear trees for farmland and their reliance on an overfished river for food, as adding to their hardships. Torres Sánchez noted that the community had not benefited from the conservation project’s proceeds despite being the custodians of the forests. Efforts to contact Puerto Franco Kichwa community members via phone were unsuccessful due to patchy cell phone service in the park region.