The extinction of the Java Stingaree represents more than just the loss of a single species. After 160 years since its only documented sighting, this small ray has become the first marine fish officially declared extinct due to human activities, according to Charles Darwin University (CDU) researchers.

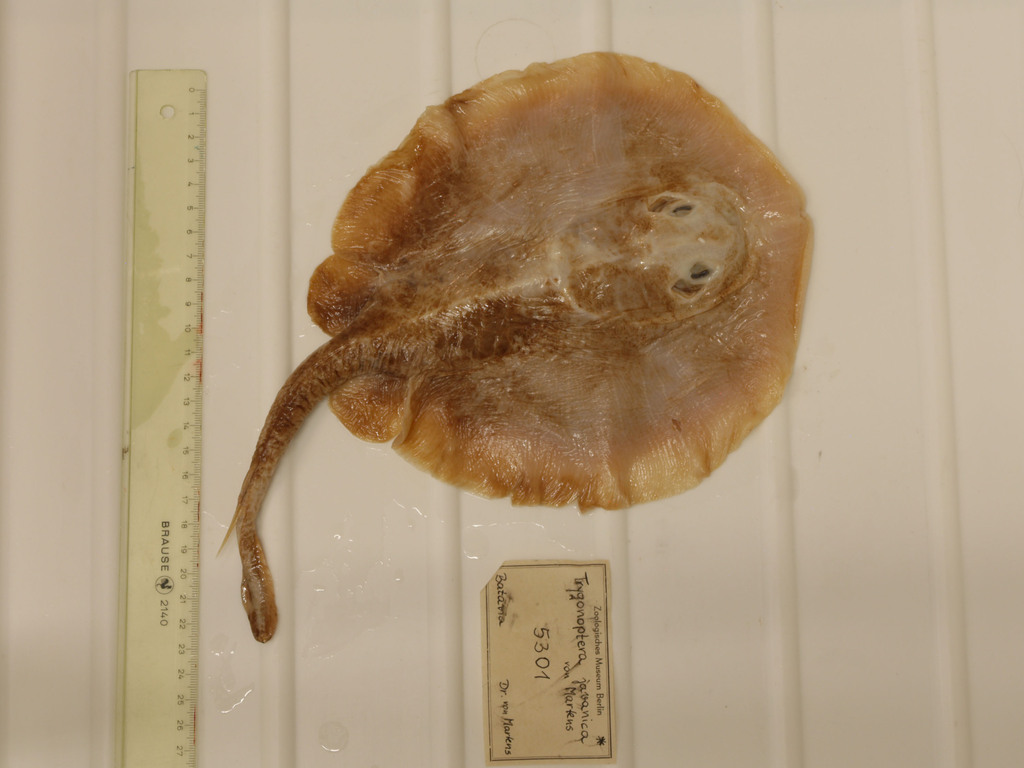

In Jakarta’s fish markets of 1862, German zoologist Eduard von Martens purchased what would become the sole recorded specimen of Urolophus javanicus. That dinner plate-sized ray, now preserved in Berlin’s Natural History Museum, represents all that remains of a species that has vanished forever from our oceans.

“Extinction is forever, and unless we can secure populations of threatened marine species around the globe, the Java Stingaree will only be the tip of the iceberg,” warns Julia Constance, CDU PhD Candidate and lead assessor on the extinction study.

The evidence for this extinction is compelling. Extensive surveys since 2001 across numerous fish landing sites along Indonesia’s northern coast have failed to yield a single specimen. The research team’s modeling assessed historical fishing records and habitat degradation trends with 95% confidence in the extinction conclusion.

Two primary factors drove this extinction. First, intensive and largely unregulated fishing in the Java Sea began depleting coastal fish populations by the 1870s, with the Java Stingaree likely caught as bycatch. Second, Jakarta Bay’s heavy industrialization destroyed critical coastal habitats where this species lived.

“These impacts were severe enough to unfortunately cause the extinction of this species,” Constance explained in the CDU press statement.

Similar Posts

The extinction signals what Dr. Peter Kyne of CDU calls “a tipping point for marine biodiversity.” With over 120 critically endangered marine fish species worldwide, the Java Stingaree’s fate offers a stark warning about human impacts on ocean ecosystems.

“The Java Stingaree being named as extinct is a warning sign for everyone across the world that we must protect threatened marine species,” Dr. Kyne stated. “We must think about appropriate management strategies like protecting habitat and reducing overfishing while also securing the livelihoods of people reliant on fish resources.”

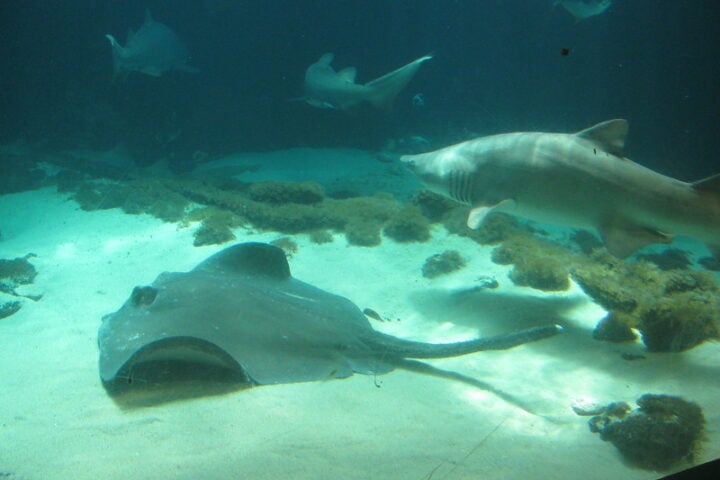

This extinction fits into a troubling global pattern. A 2021 study in Nature documented a 71% decline in global shark and ray populations since 1970. The Java Stingaree’s slow reproductive rate—common among rays—made it particularly vulnerable to rapid environmental changes and fishing pressure.

Benaya Simeon, another CDU PhD Candidate studying threatened rays in Indonesia, noted the species’ distinctiveness: “The Java Stingaree was a unique dinner plate-sized ray with no similar species in Java and the fact it has not been found during innumerable surveys confirms its extinction.”

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) made this extinction official in its updated Red List of Threatened Species in December 2023. The list now includes over 169,420 species assessed, with more than 47,000 threatened with extinction globally.

Conservation experts recommend several urgent measures to prevent similar losses: strengthening fishing regulations, protecting coastal habitats from industrial development, and balancing resource use with ecosystem preservation. Indonesia’s role in monitoring other threatened species like the Kai Stingaree (last seen in 1874) remains crucial.

The loss of the Java Stingaree represents not just an ecological tragedy but a clear signal that our approach to marine conservation requires immediate, substantive change. As we face this reality, the question becomes whether this extinction will serve as a catalyst for more effective ocean protection or simply the first in a cascade of marine species disappearances.

Frequently Asked Questions

The Java Stingaree (Urolophus javanicus) was a small ray about the size of a dinner plate that lived in the Java Sea. Its extinction is significant because it represents the first documented case of a marine fish species going extinct due to human activities. This serves as a warning sign about the vulnerability of marine ecosystems and the potential for more marine species extinctions if conservation efforts aren’t strengthened.

The Java Stingaree was discovered in 1862 when German zoologist Eduard von Martens purchased a specimen from a fish market in Jakarta. This single specimen, now preserved in Berlin’s Natural History Museum, remains the only documented example of the species ever recorded by science.

Two primary factors led to the extinction of the Java Stingaree: 1) Intensive and largely unregulated fishing in the Java Sea that began depleting coastal fish populations by the 1870s, with the Java Stingaree likely caught as bycatch, and 2) Heavy industrialization of Jakarta Bay that destroyed critical coastal habitats where this species lived. The species’ slow reproductive rate, common among rays, made it particularly vulnerable to these rapid environmental changes.

Researchers from Charles Darwin University conducted extensive surveys since 2001 across numerous fish landing sites along Indonesia’s northern coast and failed to find a single specimen. Their research team’s modeling assessed historical fishing records and habitat degradation trends with 95% confidence in the extinction conclusion. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) officially declared the species extinct in its updated Red List of Threatened Species in December 2023.

The extinction of the Java Stingaree represents what Dr. Peter Kyne of Charles Darwin University calls “a tipping point for marine biodiversity.” With over 120 critically endangered marine fish species worldwide and a documented 71% decline in global shark and ray populations since 1970, this extinction serves as a stark warning about human impacts on ocean ecosystems. It highlights the urgent need for more effective conservation measures to prevent similar losses in the future.

Conservation experts recommend several urgent measures: 1) Strengthening fishing regulations to prevent overfishing, 2) Protecting coastal habitats from industrial development, 3) Balancing resource use with ecosystem preservation, and 4) Implementing appropriate management strategies that secure the livelihoods of people reliant on fish resources while protecting threatened marine species. Indonesia’s role in monitoring other threatened species, like the Kai Stingaree (last seen in 1874), remains crucial in these conservation efforts.

![Representative Image: European Starling [49/366]. Photo Source: Tim Sackton (CC BY-SA 2.0)](https://www.karmactive.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Starlings-Drop-82-in-UK-Gardens-as-Birdwatch-2025-Reveals-Record-Low-Count-Since-1979-720x480.jpg)