Indonesia’s forest conversion scheme for bioethanol production represents an ecological tipping point that forest scientists warn could unravel irreplaceable ecosystem services. The government’s plan targets clearing an area comparable to Belgium—approximately 30,689 square kilometers of rainforest—primarily for sugarcane cultivation, with rice and other food crops serving as secondary objectives in what ecologists term “forest-to-farmland conversion at catastrophic scale.”

The mega-project’s footprint encompasses 4.3 million hectares across Papua and Kalimantan, with the Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE) in Papua alone claiming over 3 million hectares of forest carbon sinks. This area directly overlaps with the Trans-Fly ecoregion, a biodiversity hotspot where endemic mammals, birds, including birds of paradise, and rare reptiles face habitat fragmentation and potential extirpation from industrial monoculture conversion.

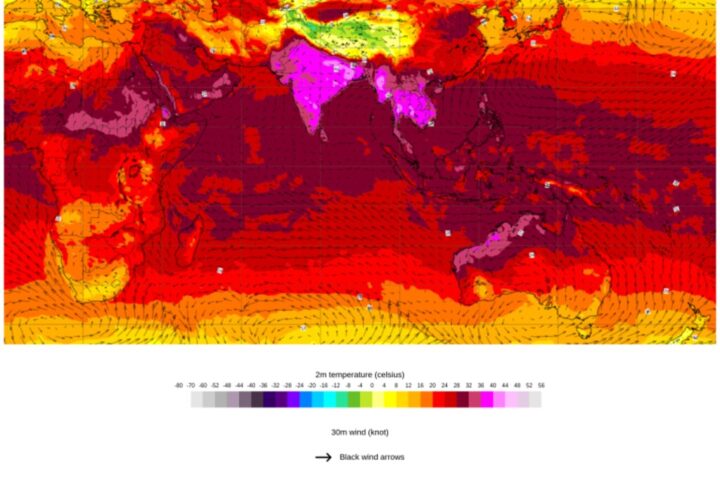

The carbon sequestration capacity being lost defies easy replacement. When forest biomass and soil organic carbon release their stored carbon, the climate implications prove staggering. An unpublished government assessment reviewed by AP estimates emissions at 315 million tons of CO₂, roughly equivalent to Poland’s annual emissions. An independent analysis from the Center for Economic and Law Studies projects that this figure might reach 782.5 million tons, representing approximately 1.6% of annual global carbon emissions from a single development project.

For the Indigenous population (estimated at 40,000), including the Marind and Yei communities, whose cultural livelihood depends on forest integrity, the ecological damage translates to direct livelihood collapse. Villager Vincen Kwipalo explained how traditional hunting grounds have already been converted to sugarcane nurseries with restricted access, severing community connections to wild protein sources, medicinal plants, and sacred sites. “We know the forests of Papua are one of the biggest lungs of the world, yet we are destroying them,” Kwipalo told reporters. “Indonesia should be proud to protect Papua… not destroy it.”

The project represents Indonesia’s intensified push toward food and energy autarky—an expansion of the “food estate” strategy championed by former President Joko Widodo and dramatically expanded under President Prabowo Subianto’s administration. “I am confident that within four to five years at the latest, we will achieve food self-sufficiency,” Prabowo stated in October 2024. “We must be self-sufficient in energy, and we have the capacity to achieve this.”

Forest canopy loss on this scale represents both historical continuity and unprecedented acceleration. Since 1950, over 74 million hectares of Indonesian rainforest—more than twice Germany’s area—have been logged, burned, or degraded for commodities ranging from palm oil to paper, rubber, and nickel. In 2023, Indonesia is said to have lost 292 kha of primary forest, equivalent to 221 Mt of CO₂ emissions. This legacy of land conversion has transformed regional hydrology, diminished forest resilience, and contributed to Indonesia’s position as a major greenhouse gas emitter.

Similar Posts

The government’s mitigation strategy hinges on a promise from Hashim Djojohadikusumo, President Subianto’s brother and environmental envoy, to reforest 6.5 million hectares of degraded land. “Thus, the food estate program continues while we mitigate the possible negative impacts with new programs, one of which is reforestation,” he assured stakeholders. However, forest ecologists consistently note that plantation forestry cannot replicate the ecosystem complexity, carbon storage capability, or biodiversity support functions of primary forests—making “like-for-like” ecological replacement scientifically impossible.

What forest ecologists term “ecosystem services tradeoffs” emerge starkly here. While the International Energy Agency recognizes bioethanol’s potential role in transport sector decarbonization, its analysis explicitly cautions that biofuel expansion requires minimal land-use impact to achieve genuine climate benefits. When primary rainforest conversion enters the equation, the net carbon balance typically shifts dramatically negative.

Despite the National Strategic Project designation streamlining the approval process, the proposal raises fundamental questions about Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) for indigenous communities. “How can the public not assume that food estate programs are merely a pretext for expanding palm oil plantations? Instead of addressing the chaos in palm oil governance, Prabowo seems intent on perpetuating it. His stance on palm oil and deforestation spells disaster for Indigenous communities, like West Papua’s Awyu people, who are currently fighting to protect their customary forests from industrial plantation expansion.”Greenpeace said Sekar Banjaran Aji, Forest Campaigner at Greenpeace Indonesia, while highlighting concerns over government policies that may prioritize industrial expansion over Indigenous land rights and environmental conservation.

The ecological stakes extend far beyond Indonesia’s borders. When mature forests representing evolutionary development across millennia face conversion to monoculture agribusiness, the genetic library of adaptations contained within countless species—many yet undocumented by science—faces permanent erasure. “Monoculture plantations such as oil palm can not only reduce the ability to sequester carbon but also suck up nutrients that are difficult to restore to natural forests.”said Andi Muttaqien, Executive Director of Satya Bumi while criticizing the government’s stance on palm oil expansion.

The corporate entities spearheading this transformation—Merauke Sugar Group and Jhonlin Group—have maintained public silence regarding environmental impact assessments. The Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture likewise declined comment requests from journalists investigating the project’s ecological and social ramifications.

As industrial chainsaws and bulldozers advance into ancient forest stands, the fundamental question emerges: Can actual national resilience emerge from ecosystem destruction, or does genuine security require intact forests providing clean water, biodiversity maintenance, carbon sequestration, and cultural sustenance? The answer will shape not just Indonesia’s national future but global climate stability and humanity’s relationship with our remaining intact ecosystems—potentially crossing ecological thresholds from which neither technology nor policy can easily return.