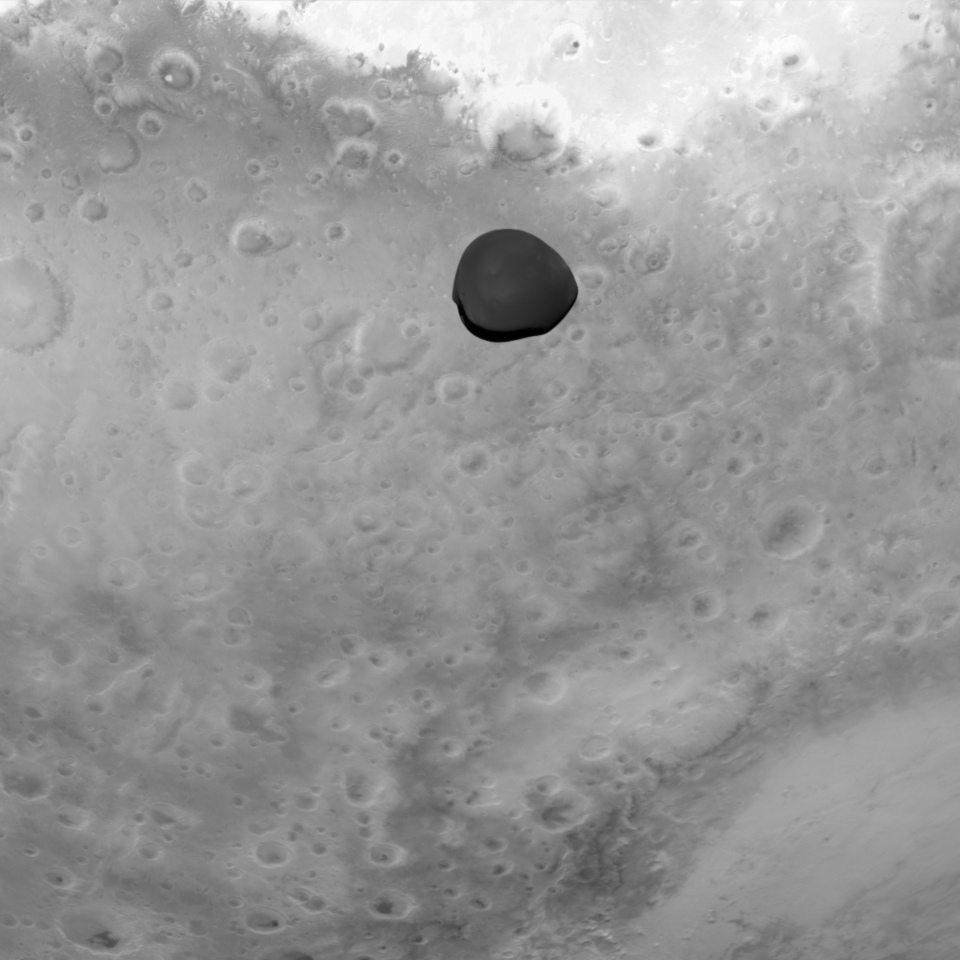

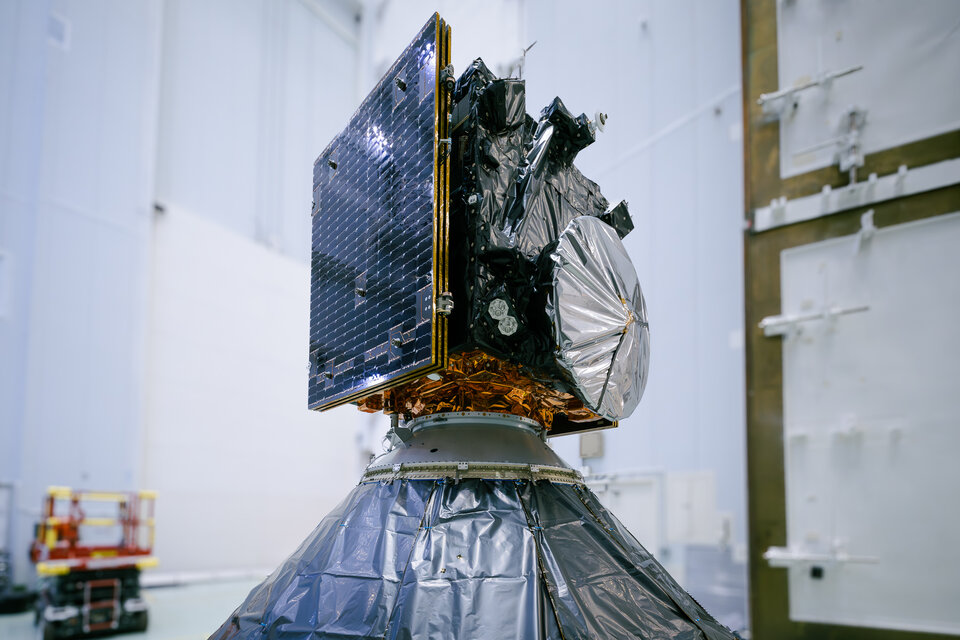

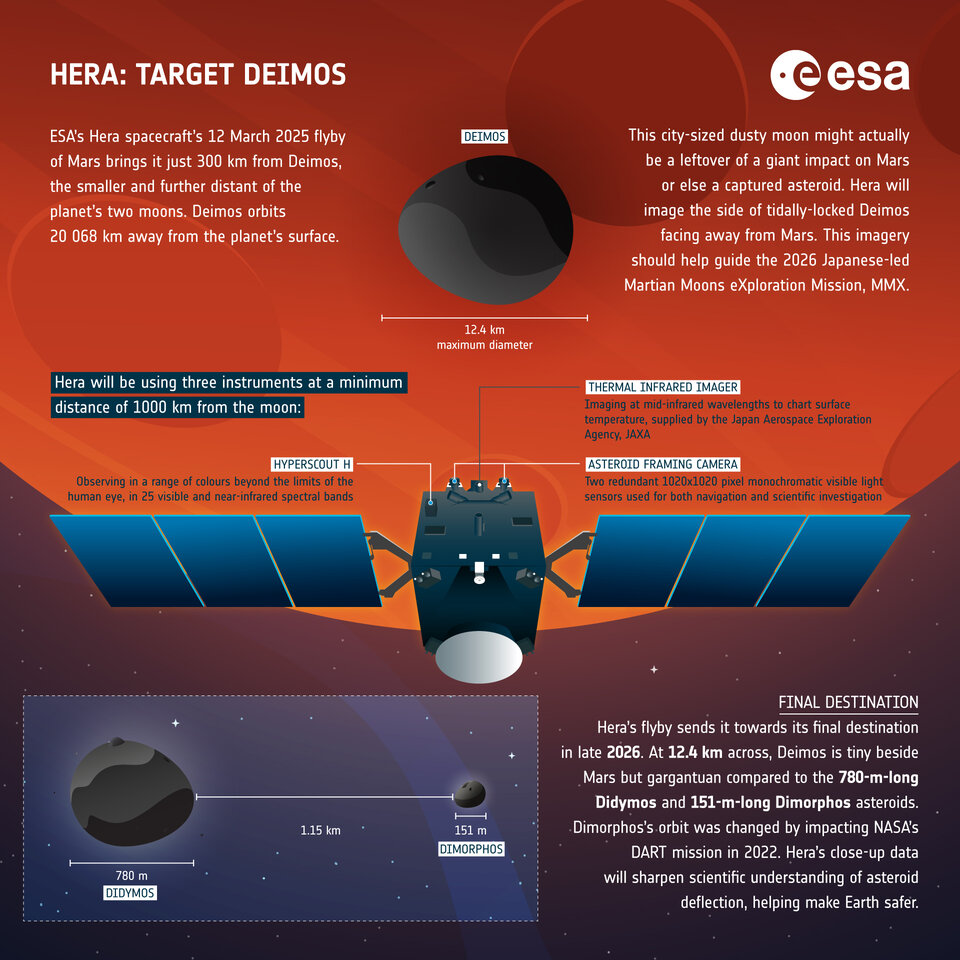

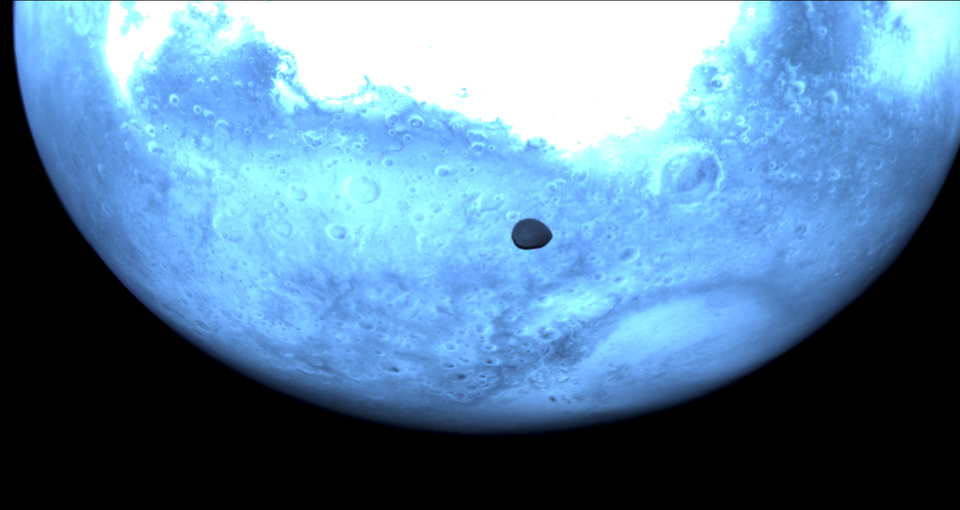

The European Space Agency’s Hera spacecraft has taken unprecedented photos of Mars’ smaller moon Deimos during a carefully planned flyby on March 12, 2025. The mission, primarily aimed at studying asteroids for planetary defense, captured detailed images of the mysterious moon from just 1,000 kilometers away.

Historic Flyby Yields Scientific Breakthrough

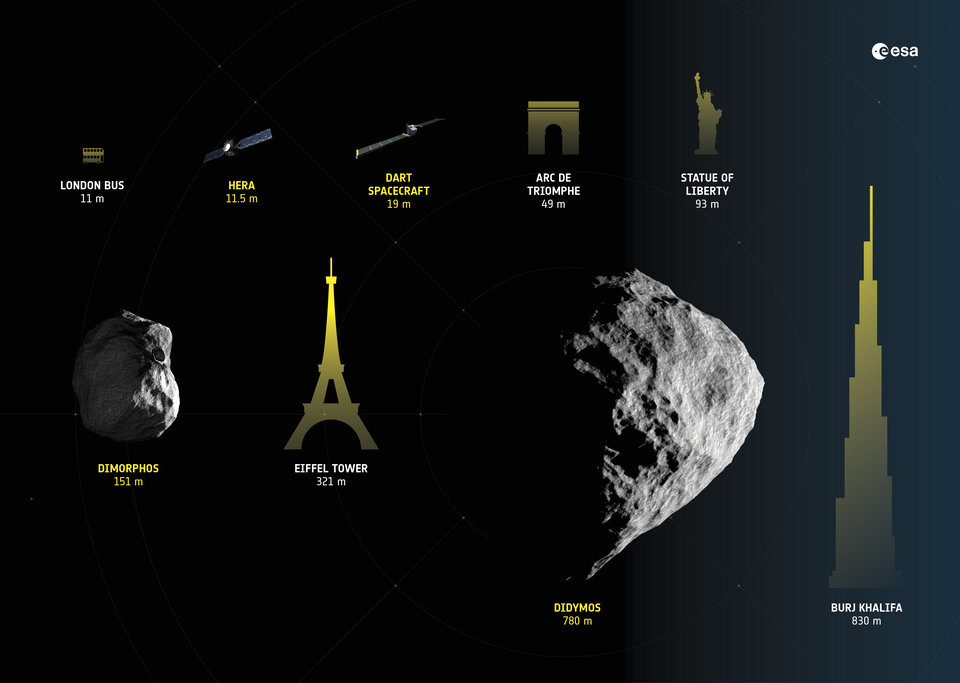

Launched in October 2024, Hera is heading toward the Didymos-Dimorphos asteroid system to study the effects of NASA’s DART mission, which successfully changed an asteroid’s orbit in 2022. The Mars gravity-assist maneuver serves a dual purpose: it shortens Hera’s journey by months while saving valuable fuel, and it provided a rare opportunity to observe Deimos up close.

“These instruments have been tried out before, during Hera’s departure from Earth, but this is the first time that we have employed them on a small distant moon for which we still lack knowledge,” explained Michael Kueppers, Hera’s mission scientist.

Moving at 9 km/s relative to Mars, Hera flew within 5,000 km of the red planet while coming as close as 1,000 km to Deimos. What makes this encounter particularly valuable is that the spacecraft observed the far side of the tidally locked moon—the side that never faces Mars.

Similar Posts:

Three Instruments Reveal Deimos’ Secrets

Hera activated three scientific instruments during the flyby:

- The Asteroid Framing Camera captured black-and-white images at 1020×1020 pixel resolution

- The Hyperscout H hyperspectral imager collected data in 25 spectral bands to analyze mineral composition

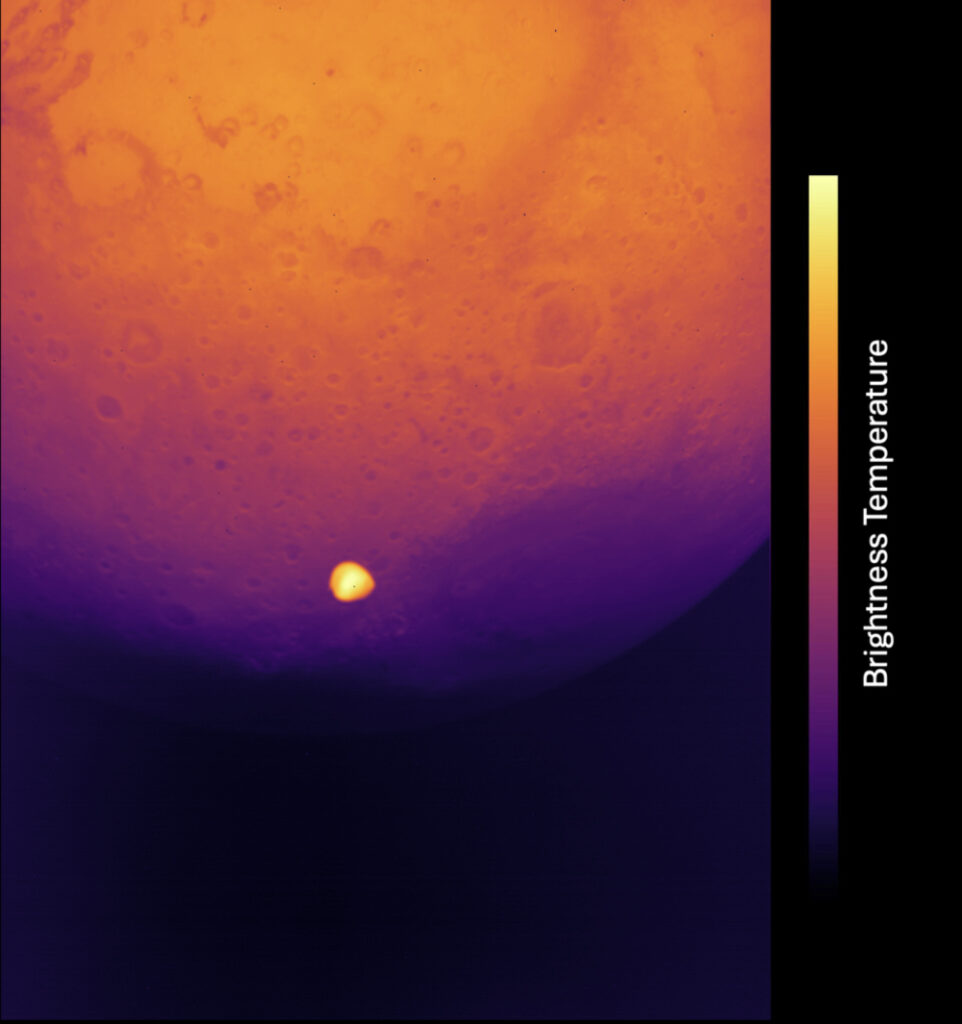

- The Thermal Infrared Imager, provided by Japan’s space agency JAXA, measured surface temperatures and physical properties

These observations may help solve the ongoing debate about Deimos’ origins—whether it’s a captured asteroid or debris from an ancient impact on Mars. Measuring just 12.4 km across, the dust-covered moon has remained somewhat mysterious despite decades of Mars exploration.

International Collaboration in Space

The mission highlights growing international cooperation in space exploration. Hera’s thermal imaging instrument comes from JAXA, and the mission conducted joint observations with ESA’s Mars Express spacecraft, which has orbited the red planet for over 20 years.

Caglayan Guerbuez, ESA’s Hera Spacecraft Operations Manager, praised the planning team: “Our Mission Analysis and Flight Dynamics team at ESOC in Germany did a great job of planning the gravity assist, especially as they were asked to fine-tune the manoeuvre to take Hera close to Deimos—which created quite some extra work for them!”

What’s Next for Hera

After this successful flyby, Hera continues its journey to the Didymos-Dimorphos asteroid system, scheduled to arrive in December 2026. There, it will conduct what ESA Hera mission manager Ian Carnelli calls a “crash site investigation of the only object in our Solar System to have had its orbit measurably altered by human action.”

The data from the Deimos encounter will also support Japan’s upcoming Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission, which plans to land on Mars’ larger moon Phobos and return samples to Earth.

Patrick Michel, Hera Principal Investigator, noted that several of Hera’s instruments weren’t activated during the flyby because of range limitations or because they’re housed on CubeSats that will deploy once the spacecraft reaches its asteroid targets.

As Hera speeds toward its final destination, it carries valuable new data about one of the solar system’s least understood moons—data that bridges planetary science with asteroid defense in a mission that showcases the best of international space cooperation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Hera is a European Space Agency (ESA) mission designed to study the effects of NASA’s DART mission, which successfully altered the orbit of the asteroid Dimorphos in 2022. Hera will provide detailed measurements of the impact crater and changes to Dimorphos, helping scientists develop asteroid deflection techniques as a planetary defense strategy. This mission represents a critical step in protecting Earth from potential asteroid impacts in the future.

The Mars flyby was primarily a gravity-assist maneuver to help Hera reach its final destination efficiently. By passing close to Mars, the spacecraft used the planet’s gravity to adjust its trajectory toward the Didymos-Dimorphos asteroid system, saving months of travel time and significant fuel. ESA’s mission planners took advantage of this necessary flyby to also observe Deimos, Mars’ smaller moon, providing valuable scientific data as a bonus objective.

Deimos is the smaller of Mars’ two moons, measuring just 12.4 kilometers across. It’s considered mysterious because scientists are still debating its origin—whether it’s a captured asteroid from the asteroid belt or debris from a giant impact on Mars. It’s tidally locked to Mars (always showing the same side to the planet), making observations of its far side rare. Its small size, irregular shape, and dusty surface have made it challenging to study in detail until now.

Hera used three main instruments during the Deimos flyby: (1) The Asteroid Framing Camera, which took visible-light black and white images at 1020×1020 pixel resolution; (2) The Hyperscout H hyperspectral imager, which collected data in 25 spectral bands beyond what human eyes can see to analyze mineral composition; and (3) The Thermal Infrared Imager (provided by JAXA), which measured surface temperatures and revealed physical properties like roughness and porosity.

Hera is scheduled to arrive at the Didymos-Dimorphos asteroid system in December 2026, about 21 months after its Mars flyby. The spacecraft will perform a follow-up maneuver in February 2026, followed by a series of “impulsive rendezvous” thruster firings starting in October 2026 to fine-tune its approach. Once there, it will conduct detailed studies of both asteroids, with particular focus on the impact site created by NASA’s DART mission.

Hera is part of an international planetary defense strategy. In 2022, NASA’s DART spacecraft intentionally crashed into Dimorphos to test if we could change an asteroid’s path—a technique that might someday protect Earth from a threatening asteroid. Hera will study the aftermath of this impact in detail, helping scientists understand exactly how effective the collision was and how asteroids respond to such impacts. This knowledge is crucial for developing reliable asteroid deflection techniques as a means of planetary defense.

![Representative Image: European Starling [49/366]. Photo Source: Tim Sackton (CC BY-SA 2.0)](https://www.karmactive.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Starlings-Drop-82-in-UK-Gardens-as-Birdwatch-2025-Reveals-Record-Low-Count-Since-1979-720x480.jpg)