A research team from the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM) and the Madrid Subterra Association is studying the feasibility of using unconventional energy sources, such as residual heat from subway stations, tunnels, and water conduits, to improve the energy efficiency of cities. Their research indicates that energy from household wastewater can save more than 50% on heating bills and that the residual heat from small subway stations could provide hot water for over 1,000 people for a year.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from human activities have devastating effects on the environment and people, especially those involving the burning of fossil fuels that generate greenhouse gases, the main cause of this severe threat. This problem is particularly critical in urban areas, where the high dependence on fossil fuels makes the population especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Cities have great potential to implement innovative solutions that improve energy efficiency and take advantage of unconventional energy sources, thereby laying the foundation for a more sustainable urban model. With this conviction, researchers from the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM), in collaboration with the Madrid Subterra Association, are promoting the exploration and exploitation of the potential for clean and renewable energy in Madrid’s urban subsoil.

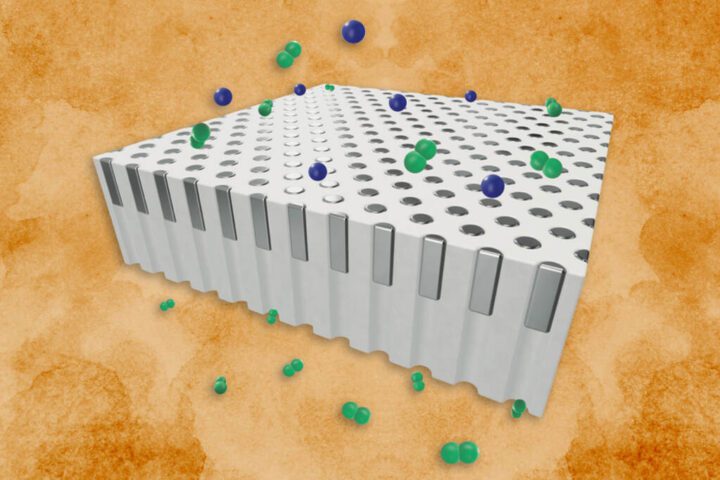

In this context, and with the aim of finding solutions to this challenge, a research team from UPM and the Madrid Subterra Association, through the Madrid company-classroom, is studying unconventional energy sources found in the city’s subsoil in the form of residual heat associated with underground infrastructure. After all, who hasn’t stood over a subway station vent to warm up on a cold winter day?

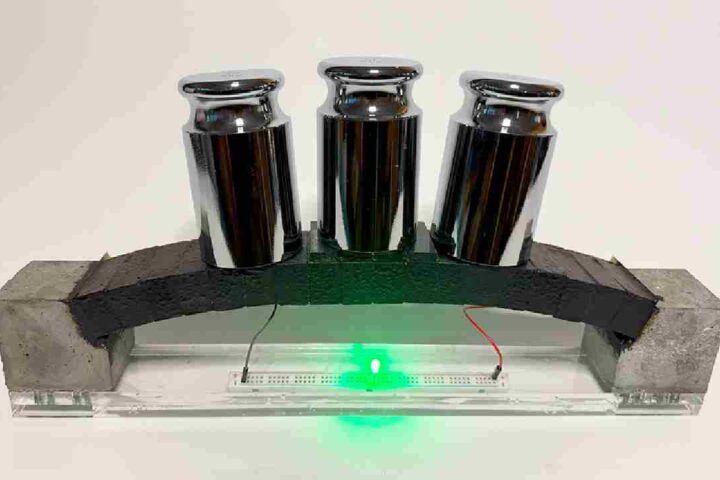

Susana Sánchez Orgaz, a researcher at UPM, stated that residual heat is heat generated but not used, thus representing free heat that ought to be utilized. She noted that this heat can be found in the subway, water conduits, and road traffic tunnels, and can be applied to building climate control or providing hot water. Sánchez Orgaz provided an example, mentioning that water from subway wells or Madrid Calle 30 could decrease the cooling consumption of their technical rooms by more than 25%.

Among the projects promoted by this research tandem are the assessment of the available energy resource in the city’s underground infrastructure, the application of this resource in the infrastructure itself or nearby buildings, and estimates of CO2 emissions savings. The main conclusion revealed by these studies relates to the high possibilities of harnessing this residual energy to reduce carbon dioxide emissions in large cities, improving their energy efficiency.

However, the researchers point out that depending on the specific type of tunnel or subway station, this utilization will be different, just as a solar panel does not produce the same energy in Seville or Lugo, so this form of energy utilization must be evaluated for each specific case.

Projects that have been carried out and continue to be conducted in collaboration between both entities include the estimation of the available energy resource in the city’s underground infrastructure, the application of this resource in the infrastructure itself or nearby buildings, both public and private, as well as estimates of CO2 emissions savings without forgetting associated costs. The main conclusion revealed by these studies relates to the high possibilities of utilizing this residual energy to reduce carbon dioxide emissions in large cities, improving their energy efficiency.

Similar Posts

The authors concluded that the utilization of residual heat would vary depending on the specific type of tunnel or subway station, highlighting similarities to the differing energy production of a solar panel in Seville versus Lugo. They emphasized the importance of evaluating this form of energy utilization for each specific case.