A genetic difference found in 4% of Greenland’s Inuit people makes their bodies handle sugar differently, putting them at a much higher risk of getting diabetes. This change in their genes, called TBC1D4, makes it ten times more likely they’ll develop the disease.

“When these people eat sugar, their body struggles to move it from their blood into their muscles,” says Professor Jørgen Wojtaszewski from the University of Copenhagen. The variant affects how insulin works in muscle tissue, making it harder for the body to control blood sugar levels.

The numbers tell a striking story. In 1962, almost no one in Greenland had diabetes – just 0.07% of the population. Today, nearly 10% of adults over 35 have the disease. For those with this special genetic trait, the outlook is more serious – 80% will develop diabetes before they turn 60.

What makes this form of diabetes different is that it only affects the muscles, not other parts of the body like the liver or fat tissue. This creates a problem for doctors because the usual warning signs of diabetes, like high blood sugar levels when fasting, don’t show up early enough.

Regular diabetes medicines don’t work well for people with this gene variant. These medicines could actually be dangerous because they might make blood sugar levels drop too low. However, there’s good news – exercise helps. Even one hour of moderate activity, like walking, makes it easier for muscles to use sugar from the blood.

Similar Posts

This genetic trait likely helped Inuit ancestors survive on their traditional diet of mostly protein and fat. But as more carbohydrates entered their diet through modern foods, this same genetic feature began causing health problems. The body’s adaptation to past conditions now faces new challenges with modern dietary changes.

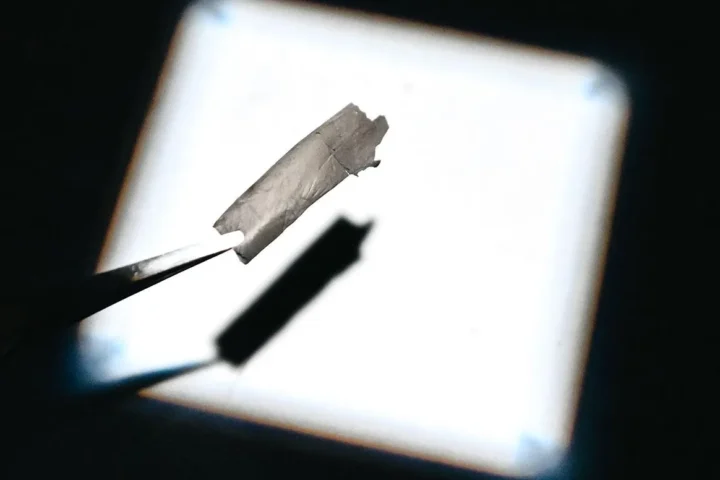

Scientists are using this discovery to develop new treatments that could help not just people with this specific genetic trait, but anyone with type 2 diabetes. They’re looking at ways to make the body’s sugar-processing system work better, focusing on the TBC1D4 protein that plays a key role in how muscles handle sugar.

Understanding this genetic variation helps identify who might need extra support early in life. It also highlights the importance of physical activity in preventing diabetes, especially for those carrying this gene variant.

The research in Greenland demonstrates how genetic traits can affect health differently as lifestyles change. It also shows the value of understanding specific genetic differences in developing better treatments and prevention strategies.