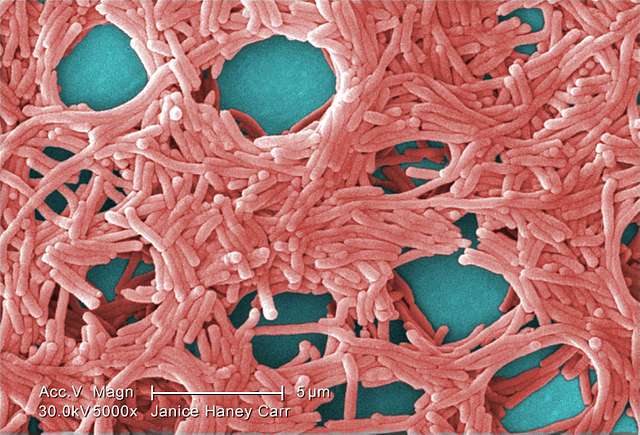

A common antidepressant may have an unexpected second job – fighting dangerous infections. New research from the Salk Institute reveals that fluoxetine, better known as Prozac, can both kill harmful bacteria and help the body defend itself against severe infections.

The discovery, published February 14, 2025, in Science Advances, shows that fluoxetine works in two key ways: it directly reduces bacterial growth and helps regulate the body’s immune response to prevent damage to vital organs. This dual action could make it valuable in treating sepsis, a life-threatening condition where the body’s response to infection spirals out of control.

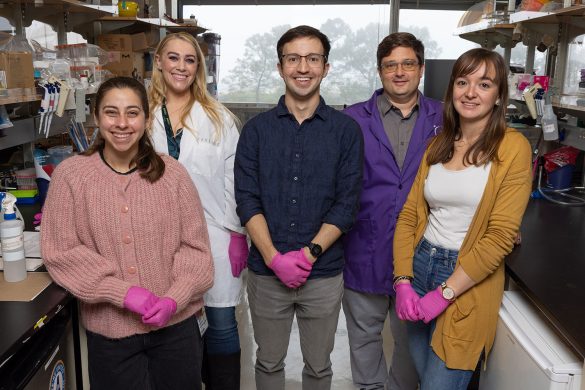

“Most medications we have in our toolbox kill pathogens, but we were thrilled to find that fluoxetine can protect tissues and organs, too,” says Professor Janelle Ayres, who led the research at Salk. “It’s essentially playing offense and defense.”

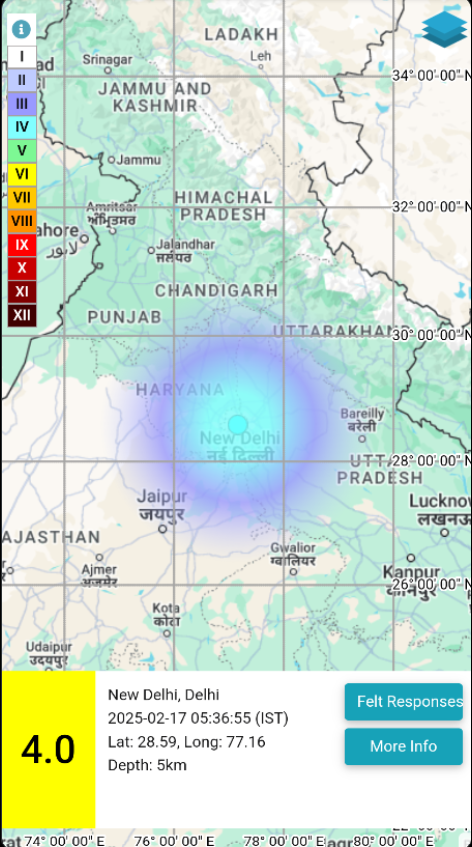

The research team tested fluoxetine in mice with bacterial infections. Animals treated with the drug before infection showed striking results – they had fewer bacteria in their systems after eight hours and were protected from sepsis, organ damage, and death.

A key finding was that fluoxetine increased levels of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory molecule that prevented a dangerous buildup of fats in the blood called hypertriglyceridemia. During infection, this helped the heart maintain proper function.

Perhaps most surprisingly, these protective effects had nothing to do with serotonin – the brain chemical that fluoxetine targets for treating depression. Mice without circulating serotonin still gained the same infection-fighting benefits from the drug.

Similar Posts:

“That was really unexpected,” says Robert Gallant, first author of the study. “Knowing fluoxetine can regulate the immune response, protect the body from infection, and have an antimicrobial effect – all entirely independent from circulating serotonin – is a huge step forward.”

The research follows earlier findings that users of SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) like Prozac had less severe COVID-19 infections and were less likely to develop long COVID.

While promising, further research is still needed. The research team is now working to determine appropriate dosing for patients with sepsis and investigating whether other SSRI antidepressants might have similar protective effects.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the NOMIS Foundation, with additional researchers from the University of Washington contributing to the work.

For doctors and patients, the possibility of repurposing an established, safe medication like fluoxetine to fight severe infections could be significant. The drug’s ability to both attack bacteria and prevent the immune system from damaging the body makes it especially interesting as a potential treatment for sepsis, which affects many patients in critical care settings.

The research also highlights how medications can sometimes have beneficial effects completely separate from their original purpose – a reminder that scientific discoveries can come from unexpected places.