Scientists at the University of Florida have created a DNA-based environmental monitoring test that detects multiple invasive snake species simultaneously, marking a shift in how wildlife managers track and remove these harmful reptiles.

The test, called tetraplex digital PCR assay, identifies DNA traces from four invasive snake species—Burmese pythons, northern African pythons, boa constrictors, and rainbow boas—in water or soil samples. The method can detect snake DNA even weeks after the reptiles have left an area.

“The initial stage was designing the molecular test, which is essentially four tests in one,” explains Brian Bahder, senior author and associate professor of vector entomology at UF/IFAS Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center. “Each test is specific to a different snake species, ensuring no cross-detection among species.”

Florida’s Snake Problem

Florida faces an overwhelming invasion of non-native species.

- Over 500 non-native species established in the state

- More than 50 non-native reptile species now permanent residents

- State and federal agencies spent over $10 million from 2004-2021 on Burmese Python management alone.

These invasive species pose severe threats to agricultural activities, harm the native ecosystems, jeopardise public safety, and tax the state economy.

“Cryptic species, like most snakes, are problematic when introduced outside of their range, as detectability is low, even in high densities,” says Sergio Balaguera-Reina, co-author and research assistant scientist.

How does the test work?

Current visual surveys detect less than 5% of Burmese pythons, making traditional monitoring largely ineffective against these elusive predators; therefore, detecting these snakes through molecular biology techniques became a necessity.

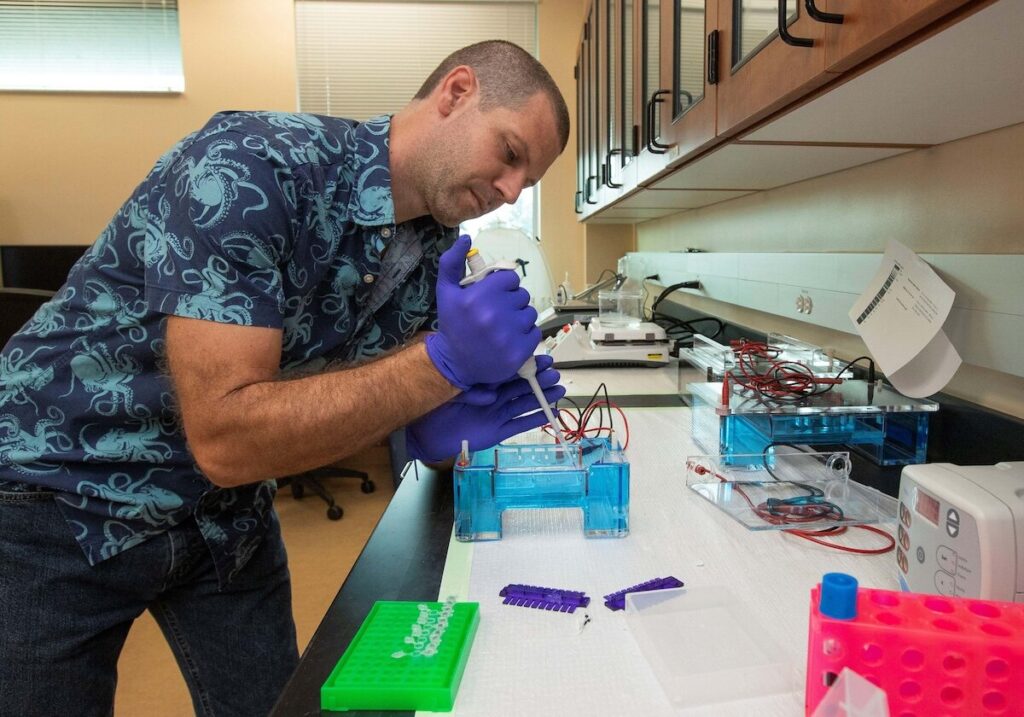

The developed technology requires researchers to conduct rigorous testing, which involves:

- Laboratory trials with known DNA concentrations in water

- Vacuum pump filtration to concentrate DNA samples

- Live Python immersion tests at various time intervals

- Field experiments showing DNA detection in soil up to two weeks after snake removal

“These concentration estimates are the first steps in a larger monitoring effort,” Bahder notes. “Further experimentation is needed to determine the effects of time, distance, and environmental factors on DNA detection rates.”

More Stories

A Cost-Effective Solution

The UF team plans to expand the test’s capabilities to include:

- Asian swamp eels

- Bullseye snakeheads

- Regional multi-species sampling network implementation

Frank Mazzotti, professor of wildlife ecology, emphasises two crucial next steps: “First, we plan on adding additional species… Second, to fully take advantage of this new methodology, we plan on implementing a regional multi-species sampling network.”

“While eDNA sampling has been applied to detect non-native wildlife, the benefit of our methodology is that we can now sample for numerous target species within a single sample,” says lead author Melissa Miller. “This can aid natural resource managers by reducing costs required to survey for non-native species in multi-invaded ecosystems.”

In conclusion, this method will remain consequential as it helps researchers operate across Florida’s varied environments, from dense Everglades to urban areas, providing wildlife managers with precise data for removal efforts and ecosystem protection strategies.