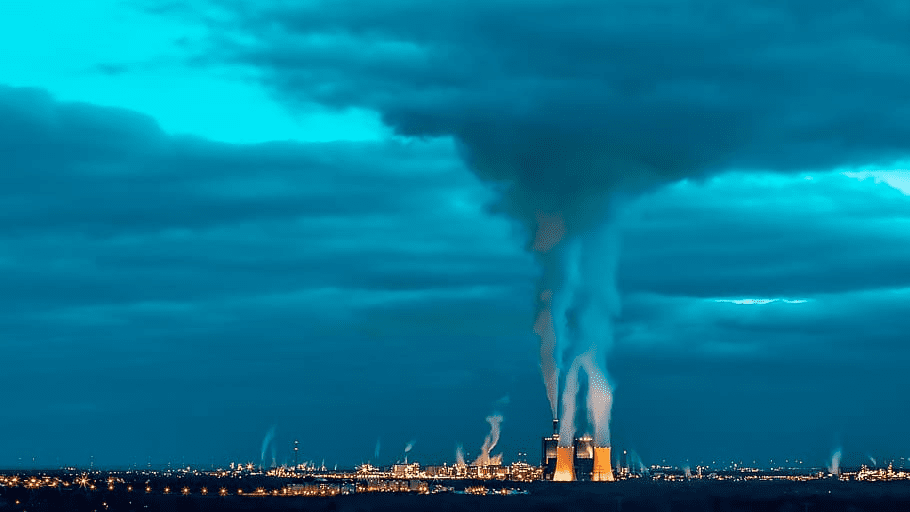

At the heart of our changing climate is a paradox. The atmosphere above the Earth is actually getting colder, while the Earth’s surface is warming. Climate models have long predicted this paradox, as it has been quantified in detail by satellite sensors. The accuracy of climate models is confirmed by the new findings, which provide evidence of a human “fingerprint” on climate change.

Published in the Journal PNAS by climate modeler Ben Santer, a recent study found that the cooling aloft increases the strength of human climate change. As this finding is “incontrovertible”, it confirms that specific signals from human activities have altered the temperature structure of Earth’s atmosphere.

The study reveals that the temperature trends in the troposphere (the lowest layer of the atmosphere) and the lower stratosphere have distinct differences, which serve as a fingerprint of human effects on climate. The research focuses on the mid-to-upper stratosphere, 25 to 50 kilometers above the Earth’s surface, and finds that including this information improves the detectability of the human fingerprint.

While the noise levels of natural variability are smaller, making the human impact more distinguishable, the cooling signal from human-caused CO2 increases in the upper stratosphere is larger.

The finding provides clear evidence that recent atmospheric and surface temperature changes cannot be attributed to rural causes. It underscores the importance of taking climate change seriously dispels claims that it is all natural. The research also raises concerns about the implications of cooling aloft for satellites, the ozone layer, and weather patterns.

The researchers have limited knowledge about the remote zones of the upper atmosphere, but recent advancements have shed light on the changes happening there. The atmosphere of Earth is composed of layers, with the troposphere being the layer closest to the surface where weather occurs.

There is a progressively less dense air layer above the troposphere, the stratosphere, the mesosphere, and the thermosphere. These upper layers are affected by high winds and large-scale air movements that can impact the weather patterns in the troposphere.

Similar Post

The increased CO2 levels cause the upper atmosphere to cool and the air to contract, which affects satellite orbits and increases the risk of collisions with space debris. The cooling and contraction of the upper atmosphere can also have implications for the ozone layer, which has been recovering from depletion caused by ozone-eating chemicals.

The formation of polar stratospheric clouds, exacerbating ozone depletion in the Arctic, can be attributed to the cooling. Weather patterns, through phenomena like sudden stratospheric warming, can be influenced by cooling aloft. This can cause significant temperature swings and disruptions to the jet stream, leading to extreme weather events and shifts in climate patterns.

The study highlights the need to consider the entire atmosphere when studying climate change. CO2’‘s influence extends beyond the troposphere, and its effects on temperature aloft are different from those at the surface. The cooling aloft contributes to the complexity of climate change and raises concerns about the impacts of satellites, the ozone layer, and weather patterns. The research emphasizes the urgency of addressing climate change based on our scientific understanding of its human-induced nature and its potential consequences for the Earth’s atmosphere and ecosystems.