Scientists at Colossal Biosciences have announced the birth of three genetically modified dire wolf pups, marking what the company calls “the world’s first successful de-extinction” of an animal species. The wolves, extinct for approximately 12,500 years, were created using DNA from ancient fossils combined with genes from their closest living relative, the gray wolf.

The three pups—two males named Romulus and Remus born in October 2024, and a female named Khaleesi born in January 2025—now live in a secure 2,000+ acre ecological preserve. They are monitored by security personnel, drones, and live camera feeds, with 10 full-time animal care staff tending to their needs.

“Our team took DNA from a 13,000-year-old tooth and a 72,000-year-old skull and made healthy dire wolf puppies,” said Ben Lamm, CEO of Colossal Biosciences. “Today, our team gets to unveil some of the magic they are working on and its broader impact on conservation.”

The Science Behind the Achievement

The process involved several steps utilizing cutting-edge genetic technology. Scientists first extracted ancient DNA from two dire wolf fossils: a tooth from Ohio dating back 13,000 years and an inner ear bone from Idaho estimated to be 72,000 years old.

After comparing these ancient genomes with those of living canids, researchers identified specific gene variants unique to dire wolves. Using CRISPR gene-editing technology, they made 20 precise edits across 14 genes in gray wolf cells to introduce dire wolf characteristics.

These edited cells were then cloned and transferred into surrogate mothers—large, mixed-breed hounds—who gave birth to the pups through a process called interspecies surrogacy.

Love Dalén, a professor in evolutionary genomics at Stockholm University and an adviser to Colossal, noted that while the resulting animals are genetically 99.5% gray wolf, they carry key dire wolf genes. “It carries dire wolf genes, and these genes make it look more like a dire wolf than anything we’ve seen in the last 13,000 years,” Dalén said.

Prehistoric Predators

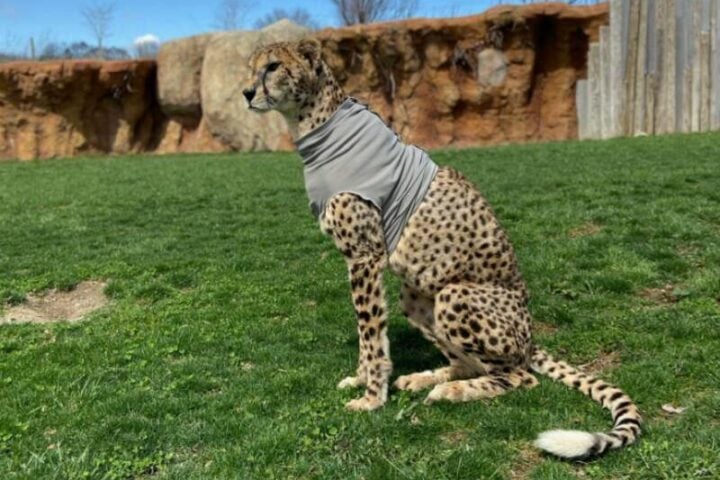

The dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus) was a top predator in North America during the Pleistocene ice ages. According to Colossal, they were about 25% larger than modern gray wolves, with a broader head, stronger jaw, and light-colored thick fur. They hunted large prey such as horses and bison.

These wolves went extinct at the end of the last ice age, around 13,000 years ago, when many of their prey species disappeared—possibly due to climate change and human hunting.

While many people associate dire wolves with the fantasy series “Game of Thrones,” where they serve as the sigil of House Stark, these were real animals that played an important role in ancient North American ecosystems.

Similar Posts:

Conservation Applications

Colossal Biosciences says the technology developed for this project has immediate applications for endangered species conservation. The company has already used techniques developed during the dire wolf project to clone red wolves, the most critically endangered wolf species, with fewer than 20 remaining in the wild.

“The technologies developed on the path to the dire wolf are already opening up new opportunities to rescue critically endangered canids,” said Matt James, Colossal’s Chief Animal Officer.

The company created a less-invasive method of establishing cell lines from blood draws rather than more invasive tissue samples, which can be used for cloning endangered animals. Two litters of cloned red wolves have already been born using this technique.

Scientific and Ethical Questions

The project raises questions about what constitutes “de-extinction.” The dire wolf pups are genetically modified gray wolves rather than pure dire wolves, leading to debate about whether this qualifies as truly bringing back an extinct species.

Christopher Preston, a professor of environmental philosophy at the University of Montana, noted that Colossal’s facility had been certified by the American Humane Society, but questioned the long-term role these animals might play.

“In states like Montana, we are currently having trouble keeping a healthy population of gray wolves on the land in the face of amped up political opposition,” Preston said. “It is hard to imagine dire wolves ever being released and taking up an ecological role. So, I think it is important to ask what role the new animals will serve.”

Other scientists have expressed concerns about resource allocation, suggesting that funds might be better used for conserving currently endangered species.

Dr. Beth Shapiro, Colossal’s Chief Science Officer, defended the approach: “Functional de-extinction uses the safest and most effective approach to bring back the lost phenotypes that make an extinct species unique.”

The company says its long-term goal is to restore de-extinct species in secure ecological preserves, potentially on indigenous land, though any reintroduction to the wild would face significant challenges.

Whatever the future holds for these engineered dire wolves, their birth represents a major milestone in genetic science and opens new possibilities for both extinct species revival and endangered species conservation.

![Representative Image: European Starling [49/366]. Photo Source: Tim Sackton (CC BY-SA 2.0)](https://www.karmactive.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Starlings-Drop-82-in-UK-Gardens-as-Birdwatch-2025-Reveals-Record-Low-Count-Since-1979-720x480.jpg)