In the present day, we know that the brain undergoes Alzheimer’s disease-related alterations that begin years before the first symptoms appear. This time is what doctors define as the “preclinical phase.” During this stage, a person may express some complaints related to memory loss; however, their performance on standard neuropsychological tests appears normal. Now, a new study from Harvard asks: Is it possible to detect these early clues of Alzheimer’s?

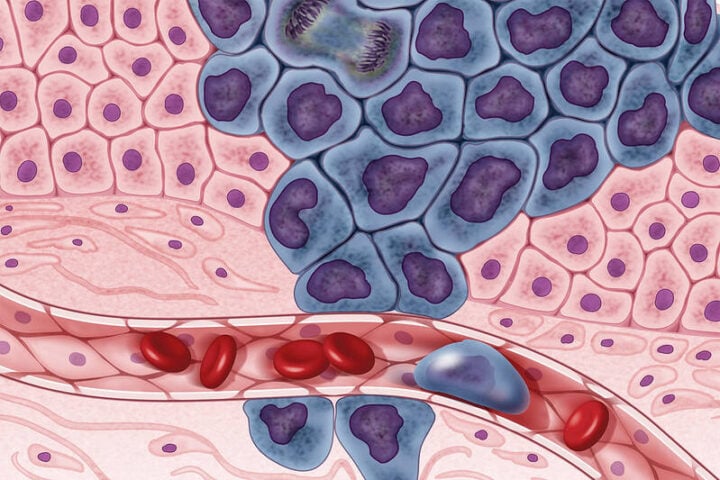

The study, published yesterday in the electronic edition of Neurology, confirms that individuals who report memory problems in an early phase and whose partners or family members also suspect them, present higher levels of tau tangles in the brain, a biomarker associated with Alzheimer’s disease.”Using imaging, the researchers found reports of cognitive decline were associated with accumulation of tau tangles — a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease,” was noted in a press release by Mass General Brigham.

“Something as simple as asking about memory complaints can track with disease severity at the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Rebecca E. Amariglio, clinical neuropsychologist and lead author of the study. “We now understand that changes in the brain due to Alzheimer’s disease start well before patients show clinical symptoms detected by a doctor.” explained Dr. Amariglio.

The study involved 675 adults with an average age of 72 years who did not have cognitive impairment in formal tests. Brain scans were performed on all participants to detect amyloid plaques. From this group, 60% had elevated levels of amyloid, meaning they were at risk of developing cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease even though they were cognitively normal at the time of the scan. Participants did not know if they had elevated levels of amyloid.

Similar Post

Each participant and their partner filled out a questionnaire to assess the participant’s subjective cognitive decline. Questions included: “Compared to a year ago, do you think your memory has substantially declined?” and “Compared to a year ago, do you have more difficulty managing money?” Scores for participants and their partners were recorded. Higher scores indicated more complaints about memory.

Among the 675 participants, the researchers found that both amyloid and tau were associated with greater self-reported decline in cognitive function. During the research, it was revealed that subjective reports from patients and partners complemented objective tests of cognitive performance.

Researchers reviewed the brain scans to detect levels of tau tangles and found that participants with higher levels of tangles had higher scores of complaints on the memory questionnaire. Their partners also rated them higher. This association was stronger in participants who had elevated levels of amyloid plaques. “There is increasing evidence that individuals themselves or a close family member may notice changes in memory, even before a clinical measure picks up evidence of cognitive impairment,” Amariglio adds.

Amariglio warns that noticing a change in cognition does not mean that one should conclude that a person has Alzheimer’s disease. Nonetheless, she states that the concern of a patient or family member about their cognition should not be dismissed. Early detection and appropriate follow-up can be crucial for the management and early intervention in Alzheimer’s disease.

Finally, the author notes that the study was limited by the fact that most participants were white and had a high level of education. The researchers emphasize the need for future studies to include more diverse participants and to follow participants over a longer period.