The Strait of Gibraltar, a narrow 14 km passage separating Europe from Africa, is one of the most significant migratory routes for birds. This natural bottleneck channels millions of birds annually as they travel between Europe and Africa. However, the journey is fraught with numerous challenges, and the impact of climate change has added new layers of complexity to this ancient migration route.

Some 400,000 storks and raptors, 750,000 seabirds, and several million small birds converge on their passage from Europe to Africa.

Increasing temperatures and changing weather conditions are affecting the routes and habitats of these birds, forcing them to adjust quickly. Scientific news media SINC wrote an article quoting well-known ornithologist Alejandro Onrubia: “It affects the barriers they have to cross and the conditions of the places where they fly and rest.” In a video for TV programme Territorio Natura, Alejandro also stated that global warming is shortening their migration routes and making them migrate sooner due to winters being lighter in Europe, making it unnecessary for them to fly to Africa to obtain food.

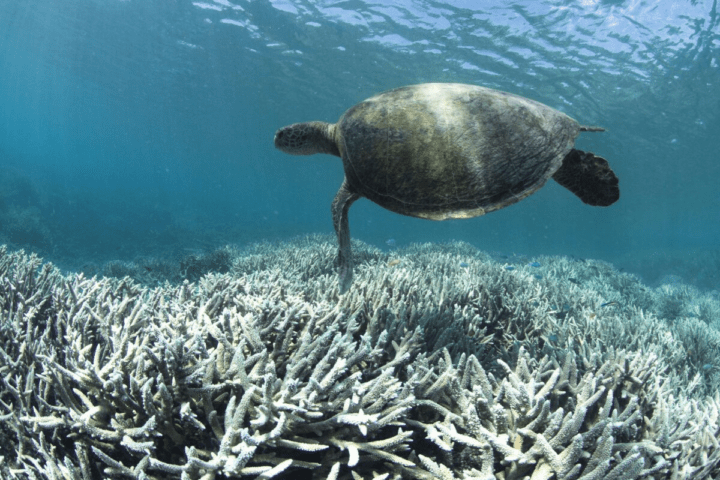

He also noticed the incorporation of African species into the European continent because the South of the Iberian Peninsula is becoming ecologically more similar to the North of Africa. Thus, starting a process of colonization which can cause an imbalance in nature as it disrupts interactions between species, not just predators and prey; birds that choose not to migrate compete with resident birds, or may even colonize previously uninhabited regions, becoming invasive species. This may evolve into serious problems such as hybridization, shortages in food, competition for nests, or even disease transmission.

Additionally, human activity such as wind turbines complicate their migration, primarily through collision risks and habitat disruption. The large turbines can be difficult for birds to detect, leading to death. A study published by Journal of Animal Ecology found that wind turbines in Tarifa, Spain where soaring birds concentrate to cross the Strait, were forced to roam around Tarifa while waiting for conditions favoring sea crossing. Similarly, wind farms can cause a habitat loss of 3 to 14% as they alter or destroy key habitats that these birds rely on for resting, feeding, and breeding during their fly. This may increase their stress and energy expenditure by taking longer routes in order to avoid them. For Alejandro, “the percentage of surface area should be taken into account when planning the installation of a new park.”

A study titled “Long-term changes in autumn migration dates at the Strait of Gibraltar reflect population trends of soaring birds,” published by Alejandro Onrubia together with three other scientists, provides significant insights into the autumn migration timing of soaring birds at the Strait of Gibraltar. By analyzing data over a 16-year period (1999-2014), they aimed to understand how migration dates have shifted and what these changes imply about bird populations and broader ecological trends.

Key Findings:

Shifts in Migration Dates: The research reveals that the autumn migration dates for several species of soaring birds have advanced over the past few decades. This shift suggests that birds are migrating earlier in the season compared to previous years.

Similar Posts

Population Trends: Changes in migration timing are correlated with population trends of the species studied. For instance, species with increasing populations tend to migrate earlier, while those with declining populations show less change in migration timing.

Environmental Factors: The study links these changes to various environmental factors, including climate change and habitat alterations. Warmer temperatures and changes in food availability at breeding grounds are likely influencing earlier departure times.

Species-Specific Patterns: Different species exhibit distinct migration patterns. For example, the migration of the Black Kite has advanced significantly, while the Griffon Vulture shows a more stable migration period. These differences highlight the varying ecological pressures and adaptability among species.

Most importantly, their results prove that species of birds that are responding to climate change by changing their migratory dates are not declining, whereas species without shift in their migration timing show a decline of their breeding populations in Europe. Another shocking discovery is that some species change their physiology in order to adapt better due to climate change. The study says that birds facing short-term environmental changes could adjust their ecological behavior through phenotypic plasticity that would allow individuals to cope with a changing environment.

Overall, the study reveals that the advancement in migration dates due to climate change can have cascading effects on the ecosystems both in Europe and Africa, as the timing of bird arrivals can affect food webs, breeding cycles, and interspecies interactions. In consequence, as climate change and habitat modification continue to shape the natural world, ongoing research and conservation efforts are essential to preserve the delicate balance of ecosystems and the species that inhabit them.