Breast cancer rates have been climbing steadily at 1% per year from 2012-2021, with even sharper increases for women under 50 and Asian American and Pacific Islander women, according to a recent report from the American Cancer Society.

While overall breast cancer death rates have dropped 44% since 1989 thanks to better treatments and earlier detection, it remains the second deadliest cancer for women after lung cancer. The report also highlighted troubling and persistent racial and ethnic disparities:

- No improvement in mortality rates for Native American women in 30 years.

- Black women 38% more likely to die vs. white women despite 5% lower incidence.

- Gap between Black and white women’s death rates has widened since 1990.

“The piece of the report that caught the headlines was the increasing incidence found for breast cancer in young women,” said Dr. Laura Collins, professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School and breast cancer specialist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

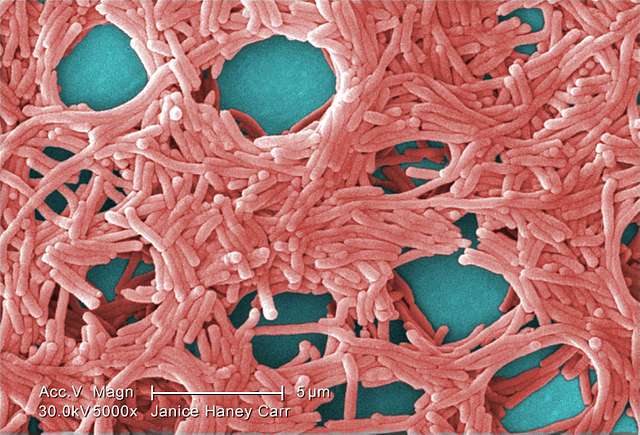

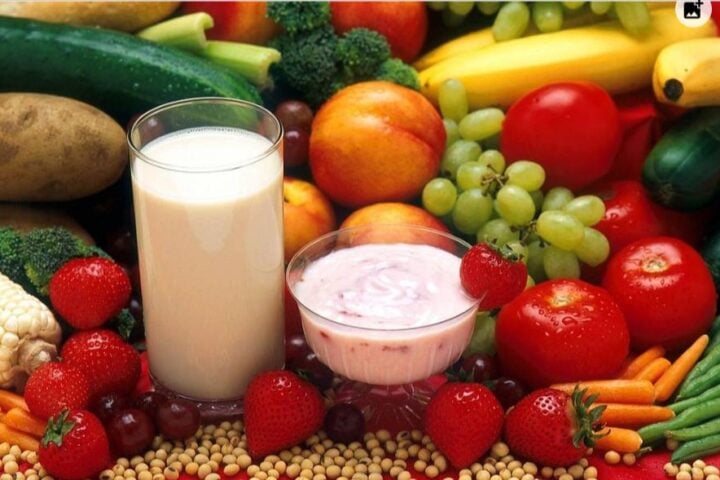

Possible factors driving the rise, especially in younger women, include:

- Postponing childbirth to later ages.

- Rising obesity rates.

- Sedentary lifestyles (exercise is known to lower breast cancer risk)

- Environmental factors like microplastics (impact still being studied)

Racial and Ethnic Disparities: A Persistent Problem

The report showed that progress against breast cancer hasn’t been equal for all women. Disturbingly, the deadly gap between white and Black women has actually widened in recent decades. Erica Warner, ScD, MPH argues these disparities “are not inevitable” and can be reduced with “better access to high-quality care and early detection.”

Factors fueling the disparities include social determinants of health, economic barriers, limited access to care, and higher rates of aggressive cancers like triple-negative breast cancer in Black women. Programs like Mary Bird Perkins’ Prevention on the Go are trying to bridge the gap by bringing mobile mammography units to underserved minority communities.

Addressing the disparities will require tackling root socioeconomic inequalities, recruiting more Black and Hispanic women for clinical trials to develop inclusive therapies, and ramping up outreach with free education and screening in underserved areas.

Similar Posts:

Key Research Developments Offer Hope

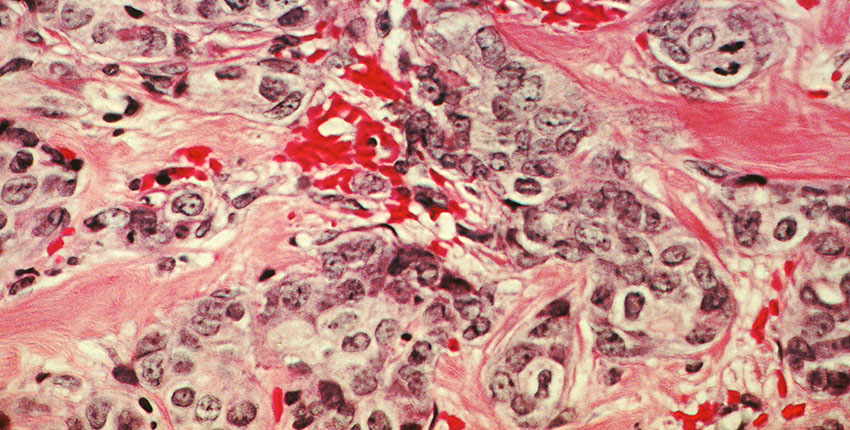

Despite the somber statistics, breast cancer experts see reason for hope. Scientists have developed promising new genetic models to understand how cancer metastasizes and find personalized treatments to stop its lethal spread.

By the next decade, treatments are predicted to become exquisitely tailored to a patient’s tumor biology using AI, augmented reality and robotics. New analyses revealing the diversity of metastatic tumors are yielding clues to someday curing even advanced cancers.

Cynthia Douglas, a breast cancer survivor, shares a deeply personal take: “Your personal health is so important. It’s so important to check yourself for lumps and schedule regular screenings.” For younger women, knowing family cancer history and other risk factors like obesity can guide early screenings, as suggested by Dr. Collins. If you notice any breast lumps or changes, promptly bring it up with your doctor – don’t let youth create a false sense of security.

Conclusion

While the latest breast cancer numbers are sobering, especially for younger and minority women, the report is a vital wake-up call for doctors, researchers, public health experts and women everywhere. By shining a light on the stark disparities and rising incidence in overlooked groups, it can catalyze change where it’s urgently needed – more inclusive research, better access to quality care, and grassroots community outreach.

Paired with cutting-edge developments in biology, technology and personalized therapies, there’s real hope for creating a future where breast cancer is less deadly, for all women. As Cynthia’s story shows, vigilance and awareness are key weapons in this fight.