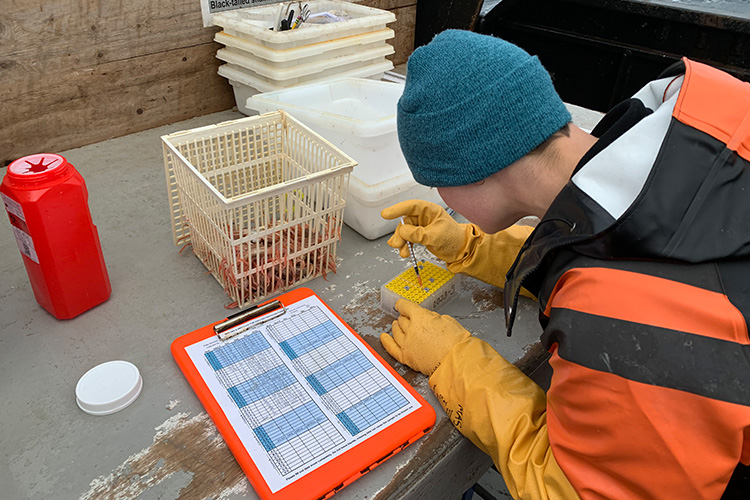

A groundbreaking study by NOAA Fisheries has uncovered alarming infection rates of bitter crab disease in the Bering Sea’s snow and Tanner crab populations, thanks to new genetic detection methods. The research shows infection levels are four times higher than previously known, with peak rates reaching 36% in snow crabs and 42% in Tanner crabs.

“That is a nearly four-fold increase in the annual prevalence levels previously detected through standard methods for disease monitoring,” says Erin Fedewa, fisheries biologist at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. Traditional visual inspection methods had estimated infection rates at less than 10% for both species.

The genetic detection breakthrough allows scientists to identify infected crabs before they show visible symptoms. In the past, researchers could only spot the disease in its late stages, when crabs developed a telling red-pink shell discoloration and milky-white blood – signs that earned the disease its name, as infected crabs develop a bitter taste.

The study’s findings are particularly concerning for smaller crabs, where infection rates climbed to over 50% in some cases. Scientists also found that the probability for infection appears higher in female snow crabs. These high infection rates among young crabs could explain why fewer crabs are surviving to adulthood to support the fishery.

Similar Posts:

The timing of these discoveries adds another piece to the puzzle of the recent snow crab population collapse. Scientists documented a 10% yearly increase in bitter crab disease from 2015 to 2017, just before the population crashed. This decline led to the closure of the snow crab fishery in 2022 – the first such closure in its history.

The economic impact has been severe. The combined snow and Tanner crab fisheries, which averaged $151 million in value from 2017 to 2021, hit a record high of $250 million in 2021. However, by 2022, the situation had become so dire that Alaska requested federal disaster assistance.

Mike Litzow, Kodiak Laboratory Director, explains the practical value of the new detection method: “With the help of genetics we can detect the disease at an earlier stage, potentially improving our forecasting capabilities to help fishermen and managers anticipate future disease outbreaks.”

NOAA scientists are now focused on monitoring disease levels while crab populations rebuild. They’re also planning long-term laboratory studies to understand how environmental factors affect disease progression and crab survival rates. This information will help develop more accurate population forecasts and guide the recovery of these valuable fisheries.

The discovery of these higher infection rates underscores the importance of genetic detection methods in marine resource management. By revealing the true scope of bitter crab disease, these tools are helping scientists and fishery managers make more informed decisions about protecting and sustaining these crucial crab populations for future generations.