Sometimes it seems as though AI is helping, but the benefit is actually a placebo effect – people perform better simply because they expect to – according to a new study by Aalto University. The study also highlights how difficult it is to shake people’s confidence in the capabilities of AI systems.

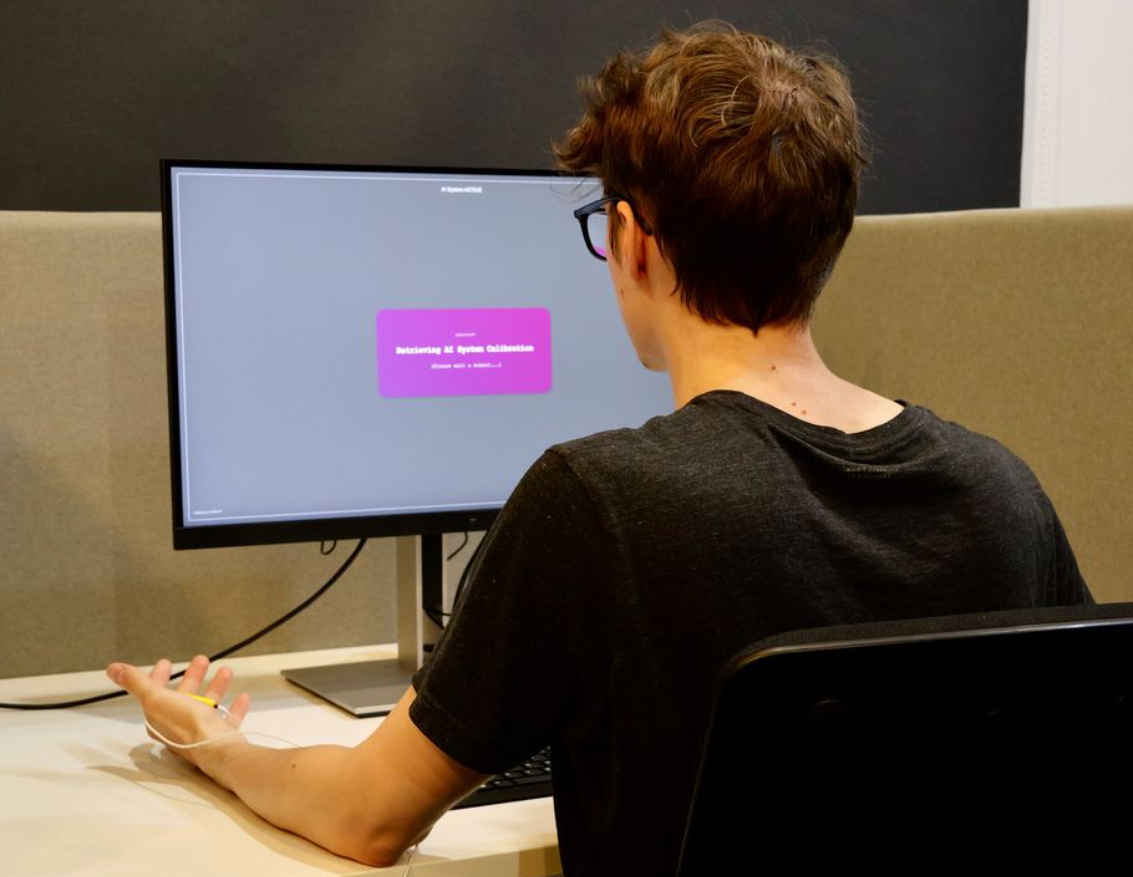

In this study, participants were tasked with a simple letter recognition exercise. They completed the task once on their own and once supposedly with the help of an AI system. Half of the participants were told that the system was reliable and would improve their performance, while the other half were told that it was unreliable and would worsen their performance.

The results were published in the conference proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. “In fact, neither AI system ever existed. Participants were led to believe an AI system was assisting them, when in reality, what the sham-AI was doing was completely random,” explains doctoral student Agnes Kloft.

The participants had to pair letters that appeared on the screen at different speeds. Surprisingly, both groups performed the exercise more efficiently – faster and more attentively – when they believed an AI was involved.

“What we discovered is that people have extremely high expectations of these systems, and we can’t make them AI doomers simply by telling them a program doesn’t work,” says Assistant Professor Robin Welsch. Following the initial experiments, the researchers conducted an online replication study, which yielded similar results.

Similar Posts

They also introduced a qualitative component, asking participants to describe their expectations of performance with AI assistance. Most had a positive outlook on AI, and surprisingly, even skeptical people still had positive expectations of its performance.

The results pose a problem for the methods commonly used to evaluate new AI systems. “This is the big realization coming from our study – that it’s hard to evaluate programmes that promise to help you.” It’s the placebo effect, says Welsch.

While powerful technologies like large language models can undoubtedly streamline certain tasks, subtle differences between versions can be amplified or masked by the placebo effect – and this is effectively leveraged through marketing. The results also present a significant challenge for research on human-computer interaction, as expectations would influence the outcome if placebo-controlled studies were not used.

“These results suggest that many studies in the field may have been skewed in favor of AI systems,” concludes Welsch.