After a century of searching, astronomers have finally confirmed the existence of four rocky planets orbiting Barnard’s Star, our cosmic next-door neighbor. Located just six light-years away, this discovery marks a significant milestone in our understanding of planetary systems around red dwarf stars.

The Breakthrough Discovery

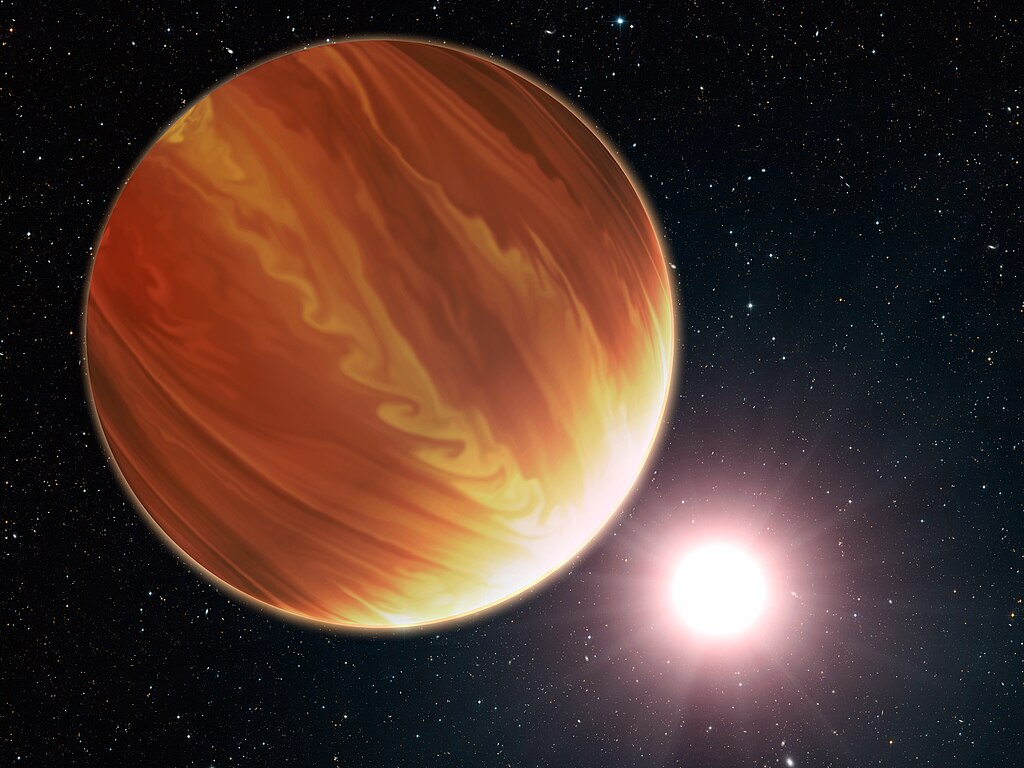

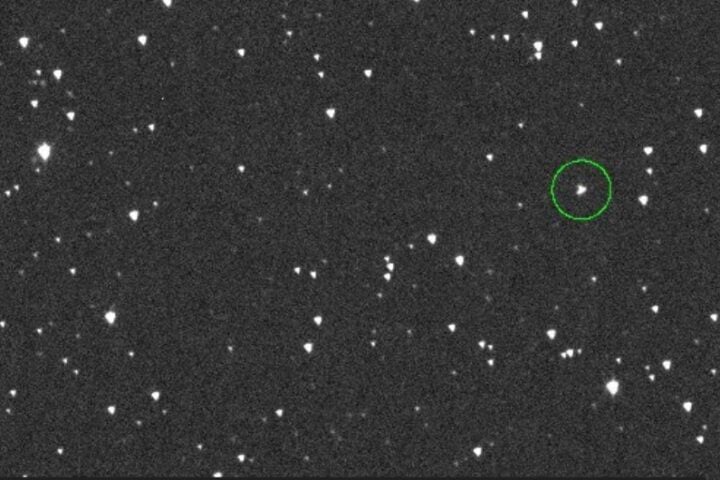

Astronomers used the MAROON-X spectrograph on the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii to detect these four small worlds. The planets range from 19% to 34% of Earth’s mass, making them some of the smallest exoplanets ever found using the radial velocity method.

“It’s a really exciting find—Barnard’s Star is our cosmic neighbor, and yet we know so little about it,” said Ritvik Basant, PhD student at the University of Chicago and first author of the study. “It’s signaling a breakthrough with the precision of these new instruments from previous generations.”

A Compact Planetary System

The four planets orbit extremely close to their host star:

- Planet d: 26% of Earth’s mass, orbits every 2.34 days at 1.7 million miles from the star

- Planet b: 30% of Earth’s mass, orbits every 3.15 days at 2.13 million miles from the star

- Planet c: 33.5% of Earth’s mass, orbits every 4.12 days at 2.55 million miles from the star

- Planet e: 19% of Earth’s mass, orbits every 6.74 days at 3.56 million miles from the star

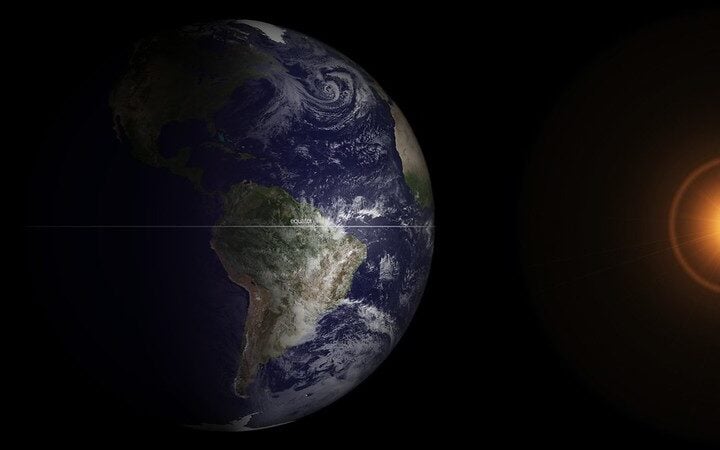

To put this in perspective, these planets are so tightly packed that the distance between some of them is just 372,820 miles—only about 1.5 times the distance between Earth and our Moon. All four planets could fit inside the orbit of NASA‘s Parker Solar Probe around our Sun.

Similar Posts

Too Hot for Life

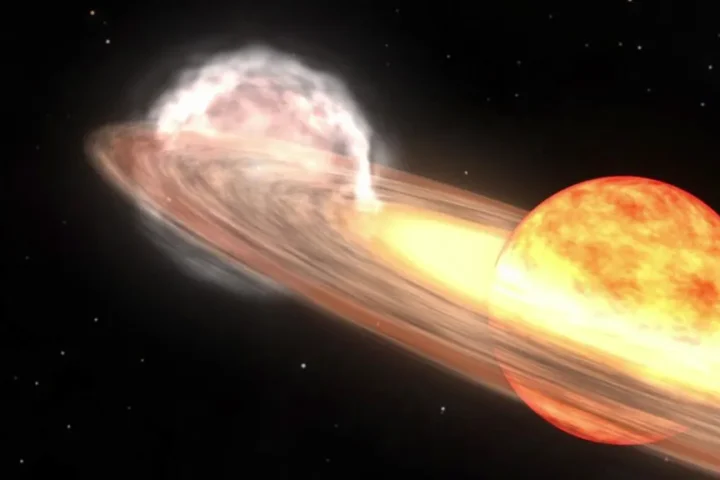

Due to their proximity to Barnard’s Star, these planets experience intense stellar radiation, making them too hot to support life as we know it. The habitable zone where liquid water could exist would be further out, with orbital periods between 10 and 42 days. So far, no planets have been detected in this region.

“With the current dataset, we can confidently rule out any planets more massive than 40 to 60% of Earth’s mass near the inner and outer edges of the habitable zone,” explained Basant. “Additionally, we can exclude the presence of Earth-mass planets with orbital periods of up to a few years.”

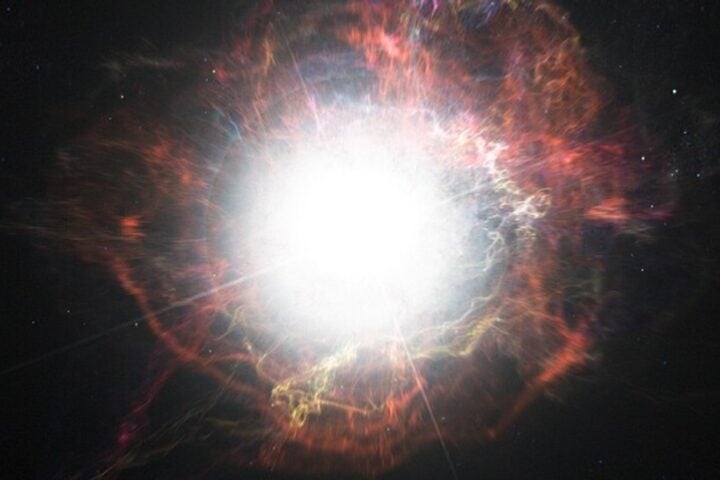

A Long Search Rewarded

Barnard’s Star has been called the “great white whale” for planet hunters. For over a century, astronomers have been studying it, with several false alarms along the way. What makes this discovery particularly reliable is that it has been independently confirmed by two different research teams using different instruments.

“We observed at different times of night on different days. They’re in Chile; we’re in Hawaii. Our teams didn’t coordinate with each other at all,” Basant noted. “That gives us a lot of assurance that these aren’t phantoms in the data.”

The Detection Method

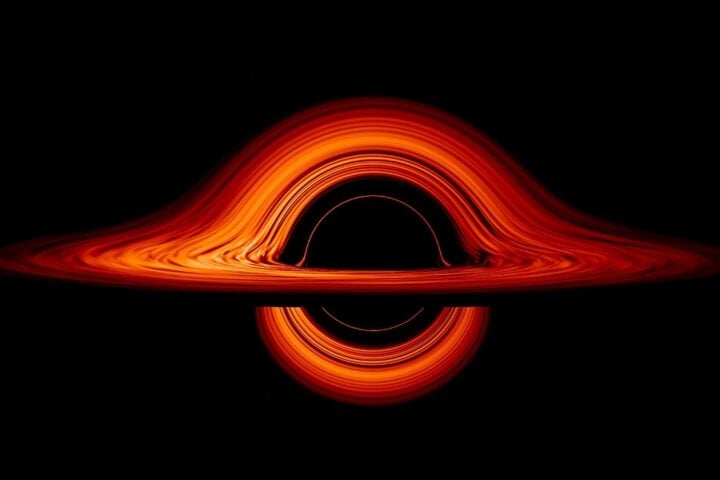

The planets were too small to see directly. Instead, astronomers measured tiny wobbles in Barnard’s Star caused by the gravitational pull of the orbiting planets—a technique known as the radial velocity method.

This approach presents challenges because red dwarf stars like Barnard’s Star have active surfaces with magnetic storms that can mimic the signature of a planet. The breakthrough came from the unprecedented precision of next-generation instruments like MAROON-X and ESPRESSO, which can detect these subtle movements.

What Comes Next

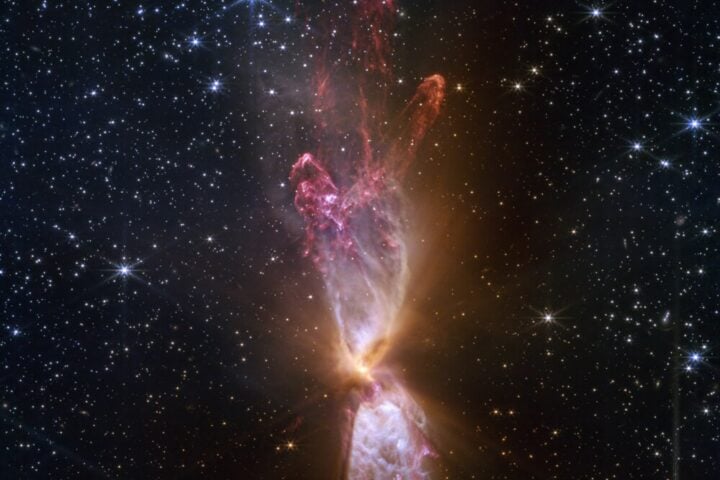

Although the planets don’t transit (pass in front of) their star from our viewpoint—which would allow for more detailed study—researchers are still optimistic about learning more about them.

“While these planets do not transit, their thermal emission can be studied with the James Webb Space Telescope, though this remains challenging,” said Basant.

Professor Jacob Bean from the University of Chicago shared the excitement of the discovery: “We found something that humanity will hopefully know forever. That sense of discovery is incredible.”

The findings were published on March 11, 2025, in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The discovery of these planets around Barnard’s Star represents a milestone in our exploration of nearby planetary systems. These findings not only showcase the capabilities of modern astronomical instruments but also expand our understanding of planet formation around the most common type of stars in our galaxy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Barnard’s Star is a red dwarf star located approximately 6 light-years from Earth, making it the second-closest star system to us after Alpha Centauri. It’s important because of its proximity to our solar system and because it’s been studied for over a century in the search for exoplanets. As a single-star system (unlike Alpha Centauri which has three stars), it provides valuable insights into planetary formation around the most common type of star in our galaxy.

No, the four planets discovered around Barnard’s Star are unlikely to support life as we know it. They orbit very close to their host star, completing revolutions in just 2 to 7 Earth days, which makes them too hot. Additionally, their proximity to the star likely means they’ve been stripped of any atmosphere due to stellar radiation. The habitable zone around Barnard’s Star would be further out, at orbital periods between 10 and 42 days, where no planets have yet been detected.

The planets were discovered using the radial velocity method, which detects tiny wobbles in a star’s position caused by the gravitational pull of orbiting planets. Specialized instruments called spectrographs (MAROON-X on the Gemini North telescope and ESPRESSO on the Very Large Telescope) measured these subtle movements with unprecedented precision. This technique is particularly effective for finding small planets around low-mass stars like Barnard’s Star.

These planets are much smaller than Earth (ranging from 19% to 34% of Earth’s mass) and orbit extremely close to their star. For comparison, all four planets around Barnard’s Star orbit within 3.56 million miles of it, while Mercury, the closest planet to our Sun, orbits at a distance of 36 million miles. The planets are also packed much closer together than in our solar system, with some separated by just 372,820 miles—about 1.5 times the distance between Earth and our Moon.

Detecting planets around Barnard’s Star has been challenging for several reasons. First, even though it’s close to us, the star is dim and the planets don’t reflect much light. Second, red dwarf stars like Barnard’s Star have active surfaces with magnetic storms that can mimic the signature of a planet, creating false positives. Finally, the technology needed to detect such small planets with sufficient precision has only recently become available with instruments like MAROON-X and ESPRESSO.

This discovery provides valuable insights into planet formation around red dwarf stars, which are the most common type of star in our galaxy. The finding suggests that small, rocky planets are likely common around these stars. Since most red dwarfs studied with sufficient precision have been found to host planets, this indicates there may be far more planets in our galaxy than stars. The discovery also helps astronomers understand how planetary systems differ from our own solar system, as Barnard’s Star hosts several small, close-in planets—a configuration not seen in our system.