In a groundbreaking archaeological discovery, researchers, led by Alice Jaspars of the University of Southampton and Ali Cameron of Cameron Archaeology, have potentially unearthed the site of the long-lost Monastery of Deer in Northeast Scotland. This site is pivotal in Scottish history, believed to be where the earliest written Scots Gaelic was added to the revered Book of Deer.

Key Findings and Historical Significance

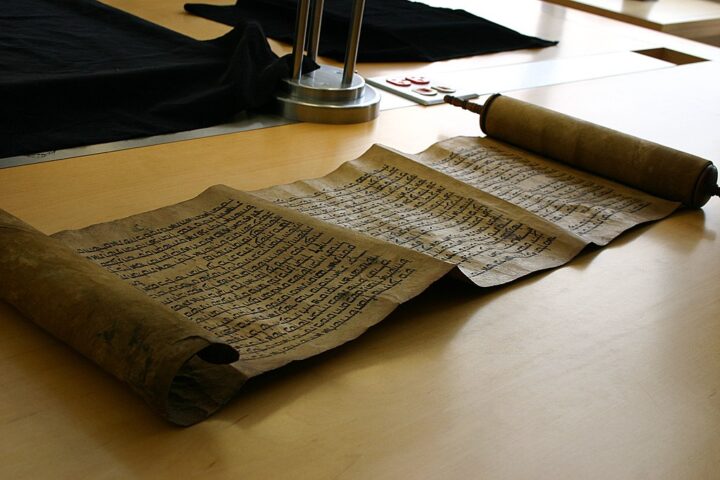

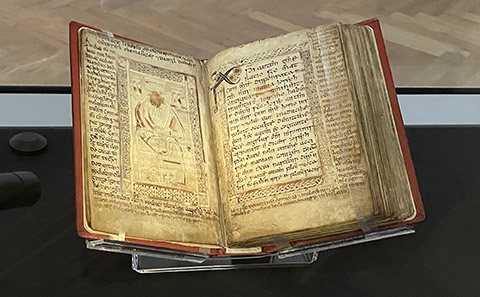

The Book of Deer, a pocket gospel book dating between 850AD and 1000AD, is renowned for containing the earliest surviving Scots Gaelic texts. These texts, primarily Gaelic land grants, were inscribed in the book’s margins in the late 11th and early 12th century. Academics have long speculated that these additions were made at the Monastery of Deer, an assertion now bolstered by the recent archaeological findings.

The recent excavation, conducted just 80 meters from Deer Abbey’s ruins near Mintlaw in Aberdeenshire, has unveiled compelling evidence. The team carbon-dated material linked with post holes they discovered, aligning with the same period as the Gaelic addenda in the book. Additionally, the recovery of medieval pottery, glass fragments, a stylus, and hnefatafl boards—a popular medieval game—further suggests a monastic complex.

The Role of Technology and Funding in the Discovery

This significant breakthrough was made possible through advanced archaeological methods and substantial financial backing. The National Lottery Heritage Fund played a crucial role in funding the project, underlining the importance of financial support in historical and cultural preservation.

Similar Posts

Exhibition and Future Plans

Coinciding with the discovery, the Book of Deer returned to Northeast Scotland for the first time in a millennium. Displayed at Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums on a three-month loan from Cambridge University Library, this exhibition provided a tangible connection to the region’s rich heritage.

Looking ahead, the researchers aim to publish their findings in an academic journal, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of monastic life in medieval Scotland. Alice Jaspars emphasizes the significance of these finds in enhancing our comprehension of the period, a sentiment echoed by the academic community.

“The material record of monasteries from this period is so poor that finds such as these can really help to inform our overall academic understanding. This also adds to the ongoing discussion regarding where the Book of Deer is cared for in the future.”

– Alice Jaspar’s, PhD Researcher from the Archaeology Department at the University of Southampton

Implications for Scottish Heritage and Language

The discovery of the Monastery of Deer holds immense importance for Scottish heritage, particularly in understanding the origins and evolution of the Scots Gaelic language. It not only provides insights into linguistic development but also into the socio-cultural dynamics of medieval Scotland.

A Collaborative Effort

The success of this project is a testament to the collaborative efforts of archaeologists, researchers, and volunteers. Their dedication and meticulous work have brought to light a crucial chapter in Scottish history, underpinning the importance of teamwork in archaeological endeavors.

Concluding Remarks

The unearthing of the Monastery of Deer is more than just a significant archaeological find; it is a window into the past, offering a unique glimpse into early medieval Scotland and the origins of Scots Gaelic. As research continues, each piece of pottery, fragment of glass, and ancient manuscript contributes to a deeper understanding of our shared history.

This discovery is not just an end but a beginning—a catalyst for further exploration and understanding of a time that has long captivated historians and laypersons alike. As the academic world eagerly awaits the publication of these findings, the Monastery of Deer stands as a beacon of Scotland’s rich and complex past.