Ethanol flows through nature’s ecosystems, challenging previous assumptions about alcohol consumption being unique to humans. Research published in Trends in Ecology & Evolution reveals how animals regularly consume and process alcohol through natural food sources, with some species developing remarkable tolerance levels.

“We’re moving away from this anthropocentric view that ethanol is just something that humans use,” explains Dr. Kimberley Hockings from the University of Exeter’s Centre for Ecology and Conservation. “It’s much more abundant in the natural world than we previously thought, and most animals that eat sugary fruits are going to be exposed to some level of ethanol.”

Fermented fruits typically contain 1-2% alcohol by volume (ABV), though researchers discovered overripe palm fruits in Panama reaching 10.3% ABV – approaching wine-level concentrations. Ethanol emerged approximately 100 million years ago alongside flowering plants producing sugar-rich nectar and fruits. Concentrations are higher and production occurs year-round in lower-latitude and humid tropical environments compared to temperate regions.

Oriental hornets stand out among alcohol-consuming species, demonstrating unprecedented tolerance. Research from Tel Aviv University documents these insects consuming large quantities of alcohol without showing intoxication or adverse effects. Dr. Sofia Boucebti’s research reveals these hornets harbor special yeasts in their digestive systems, potentially explaining their exceptional alcohol processing abilities.

Chimpanzees in Guinea’s Bossou region use leaf tools to access fermented palm sap containing 3.1% ABV. Animals already harbored genes that could degrade ethanol before yeasts began producing it through anaerobic sugar metabolism.

“From an ecological perspective, it is not advantageous to be inebriated as you’re climbing around in trees or surrounded by predators at night – that’s a recipe for not having your genes passed on,” notes researcher Matthew Carrigan. “It’s the opposite of humans who want to get intoxicated but don’t really want the calories – from the non-human perspective, the animals want the calories but not the inebriation.”

Primates and treeshrews developed efficient ethanol metabolism mechanisms through evolutionary adaptation. These species can extract nutritional benefits while avoiding intoxication, demonstrating natural selection’s role in alcohol tolerance.

More Stories

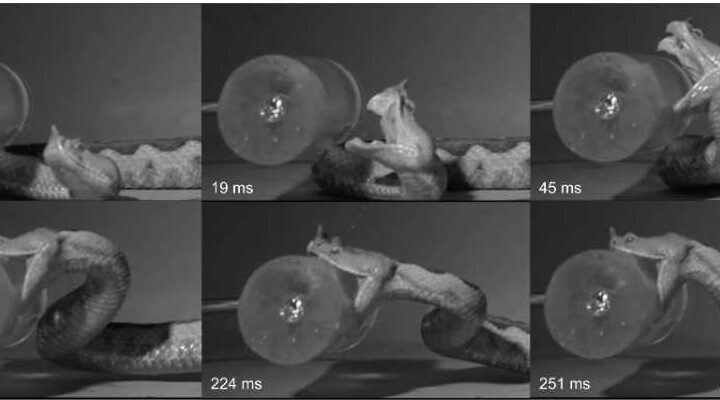

Fruit flies actively choose ethanol-rich environments for egg-laying, as alcohol protects their offspring from parasites. Some animals might benefit from ethanol’s antimalarial properties, though researcher Anna Bowland notes this requires further investigation: “Whether or not other animals use ethanol for medicinal purposes, particularly in natural contexts, still requires further research.”

Male fruit flies increase alcohol consumption after mate rejection, suggesting potential emotional or social factors in animal alcohol consumption. “On the cognitive side, ideas have been put forward that ethanol can trigger the endorphin and dopamine system, which leads to feelings of relaxation that could have benefits in terms of sociality,” Bowland explains.

Scientists acknowledge several unexplored areas:

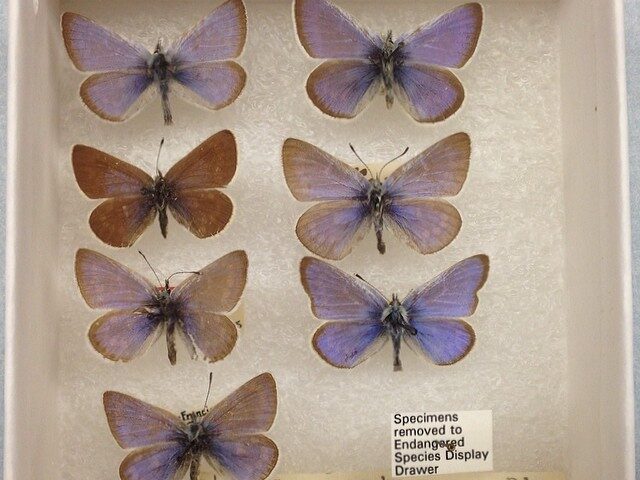

- Precise ethanol concentrations in wild food sources

- Intentional versus accidental consumption patterns

- Long-term effects on animal social behaviors

- Seasonal variations in natural alcohol availability

- Genetic mechanisms enabling specific species’ alcohol tolerance

The research team, supported by the Primate Society of Great Britain, Wenner-Gren Foundation, Canada Research Chairs programme, and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, continues investigating these questions.

“To study this behaviour in the wild requires knowledge of the natural ethanol concentrations within foods ingested by wild animals and whether animals feed on them at times when ethanol is expected to be present,” Bowland explains. Tracking unhabituated animals and measuring exact ethanol concentrations in their food sources presents ongoing technical challenges.

This research opens new avenues for understanding evolution, animal behavior, and ecological relationships. Future studies will examine behavioral and social implications of ethanol consumption in primates and investigate specific enzyme pathways involved in alcohol metabolism across species.