For years, scientists have debated whether humans or climate change caused the decline in the population of larger mammals over the past several thousand years. A recent study from Aarhus University has proved that climate change was not the actual cause of the extinction of giant mammals; instead, it was humans.

About 100,000 years ago, the first modern humans migrated out of Africa. Their exceptional ability to adapt to new environments allowed them to establish themselves in almost every type of setting, including the freezing taiga in the far north, jungles, and deserts.

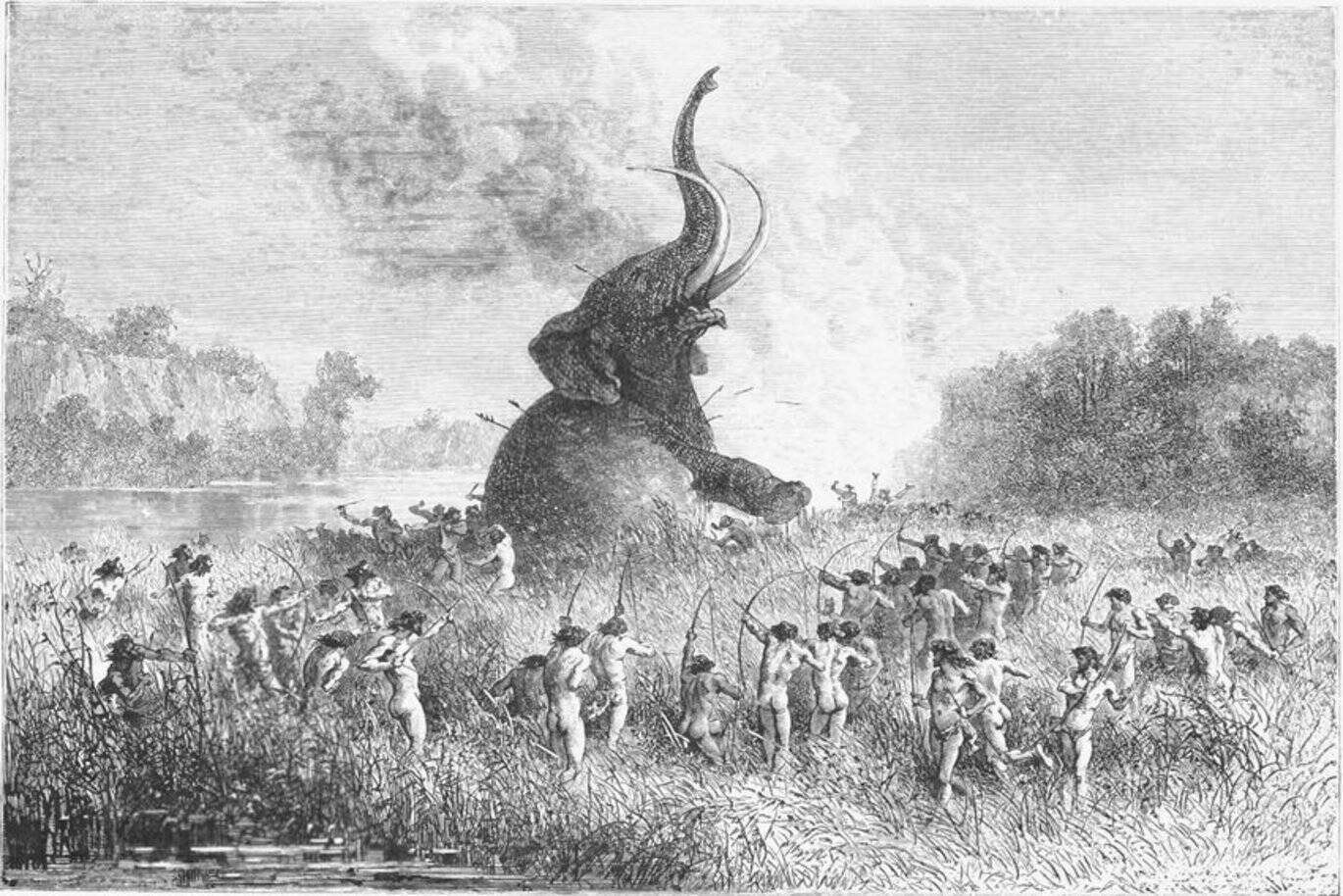

Humans had the ability to hunt larger animals using the weapons they built and their hunting techniques. They even managed to hunt down and kill the most dangerous giant mammals. However, the success of our ancestors came at a significant cost. The giant mammals are either extinct or on the verge of becoming history. Researchers have shown that the animals that survived the past 50,000 years without becoming extinct also experienced a decline in their populations over that period.

Similar Posts

During the reign of modern humans (Homo sapiens), it is a well-known fact that numerous large species went extinct. Recent research from Aarhus University reveals that those large mammals that survived also experienced a dramatic decline in population. By studying the DNA of 139 living species of large mammals, scientists have been able to show that the abundances of almost all species fell dramatically about 50,000 years ago.

Fossils from the last 50,000 years have provided some of the most significant evidence in this matter. They reveal how the global expansion of modern humans roughly matches the strong, selective extinction of large animals both on earth and over time. As a result, it is difficult to link the extinction of these animals to climate change, though there is still some disagreement.

“We’ve studied the evolution of large mammalian populations over the past 750,000 years. For the first 700,000 years, the populations were fairly stable, but 50,000 years ago the curve broke and populations fell dramatically and never recovered, For the past 800,000 years, the globe has fluctuated between ice ages and interglacial periods about every 100,000 years. If climate was the cause, we should see greater fluctuations when the climate changed prior to 50.000 years ago. But we don’t. Humans are therefore the most likely explanation.”

Jens-Christian Svenning, a professor and head of the Danish National Research Foundation’s Center for Ecological Dynamics in a Novel Biosphere (ECONOVO) at Aarhus University, and the initiator of the study.

DNA sequencing has undergone a revolution in the last 20 years. The DNA of numerous species has now been mapped, as it has become simple and affordable to map whole genomes. Assistant Professor Juraj Bergman, the lead researcher behind the new study conducted by Aarhus University, explained that there are freely accessible mapped genomes of species all over the globe on the internet, which is the data the research group utilized for their study.

“We’ve collected data from 139 large living mammals and analysed the enormous amount of data. There are approximately 3 billion data points from each species, so it took a long time and a lot of computing power, “DNA contains a lot of information about the past. Most people know the tree of life, which shows where the different species developed and what common ancestors they have. We’ve done the same with mutations in the DNA. By grouping the mutations and building a family tree, we can estimate the size of the population of a specific species over time.

Juraj Bergman, Assistant Professor, department of Biology and the lead researcher in the study by Aarhus University.

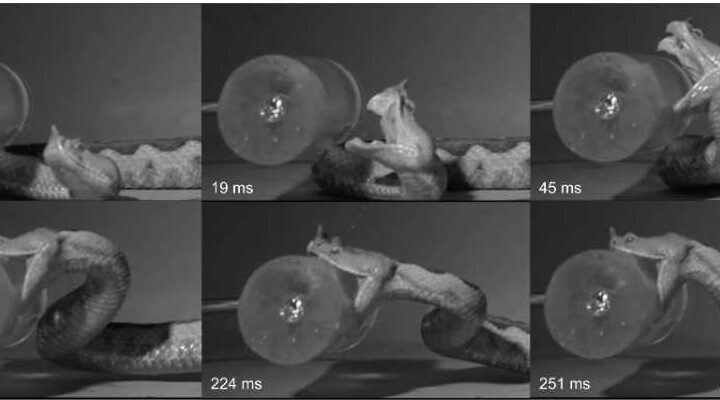

The larger the population of an animal, the more mutations will occur. It’s really a question of simple mathematics. Take elephants, for example. Every time an elephant is conceived, there’s a chance that a number of mutations will occur, and it will pass these on to subsequent generations. More births means more.

The woolly mammoth has often been central to discussions about the decline or extinction of large animals. However, Jens-Christian Svenning points out that this focus may be misleading. The majority of megafauna species that disappeared were actually associated with warmer, temperate or tropical climates, not the colder environments typically associated with woolly mammoths.

This insight is part of a broader study involving 139 large animal species that still exist today, including antelopes, elephants, bears, and kangaroos. These particular species were selected to help researchers understand changes in megafauna populations over the last 40,000 to 50,000 years—a critical period when many similar large creatures went extinct. The study’s findings are part of a growing body of research that aims to provide a clearer picture of megafauna dynamics, contributing to our understanding of the Earth’s 6,399 known mammal species.