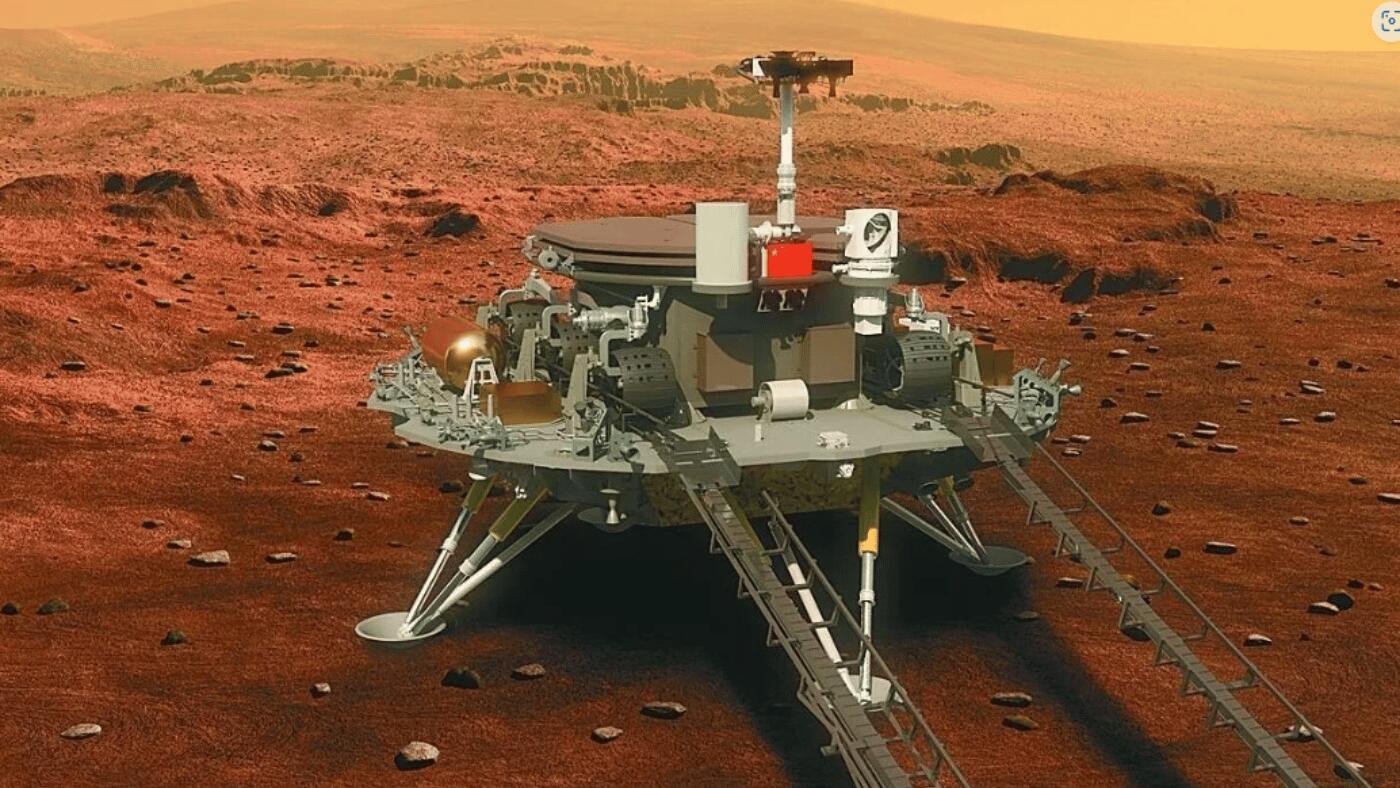

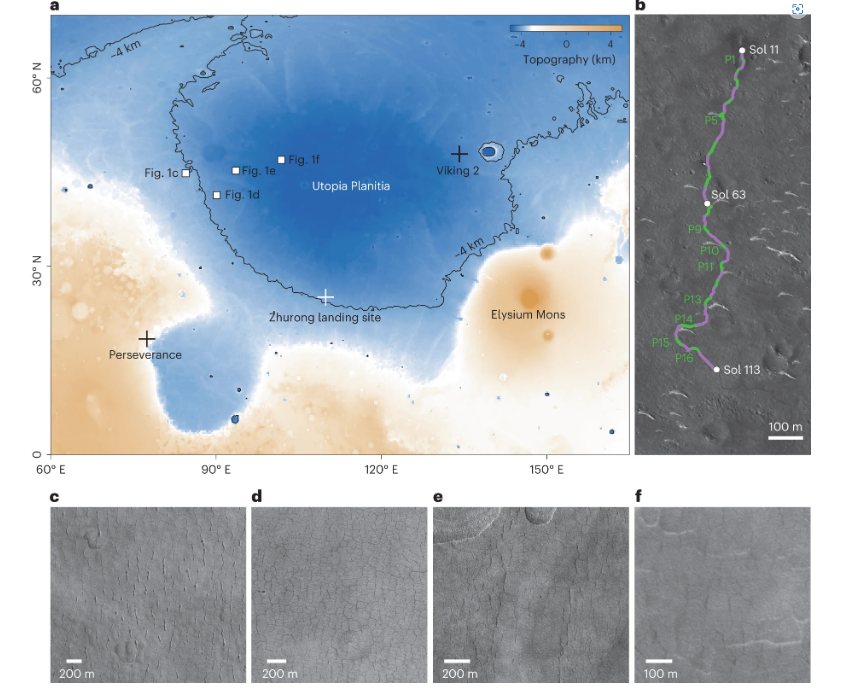

China’s Zhurong rover, a key component of the Tianwen-1 mission, has made a remarkable discovery beneath the surface of Mars. Utilizing its ground-penetrating radar, Zhurong detected irregular polygonal wedges in the Utopia Planitia region, a significant finding that could potentially reshape our understanding of the Red Planet’s history and climate. This discovery, reported in Nature Astronomy, marks a pivotal moment in Martian exploration.

Utopia Planitia, the largest recognized impact basin on Mars and in our solar system, has been a subject of intrigue for scientists for decades. Zhurong’s landing here and subsequent discoveries have added to the site’s historic significance. The detected polygons, approximately 35 meters below the surface, are thought to be a result of freeze-thaw cycles, according to Lei Zhang and his team at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The polygons could have formed from water and ice during freeze-thaw cycles, suggesting a significant paleoclimatic variability in the Martian climate. The existence of these cycles points towards a time when Mars may have had a considerably different climate than it does today. As Leonard David, a space journalist, noted, “The Chinese researchers are proposing that the polygons were potentially generated by freeze-thaw cycles.”

Similar Posts

Launched in May 2021, the Zhurong rover had a primary mission duration of 90 sols but exceeded expectations by functioning for over a year. Although it has been silent since May 2022, the data it sent back continues to provide valuable insights. Zhurong’s journey, covering approximately 1.2 kilometers, allowed for an in-depth subsurface study, revealing 16 polygonal wedges indicative of a broader distribution of such terrain in the Utopia Planitia.

These discoveries hold significant implications for understanding Mars‘ climatic history and the potential for ancient water bodies. The presence of polygons formed by freeze-thaw cycles suggests that Mars may have had conditions suitable for liquid water, raising questions about past life on the planet. This also impacts future Mars missions, especially those focused on uncovering signs of past life or planning human colonization.

While these findings are promising, it’s essential to approach them with a critical eye. The exact origins of these polygons, whether purely from freeze-thaw cycles or cooling lava flows, remain a subject of debate. This uncertainty calls for further exploration and analysis to unravel the complex history of Mars’ climate and geology.