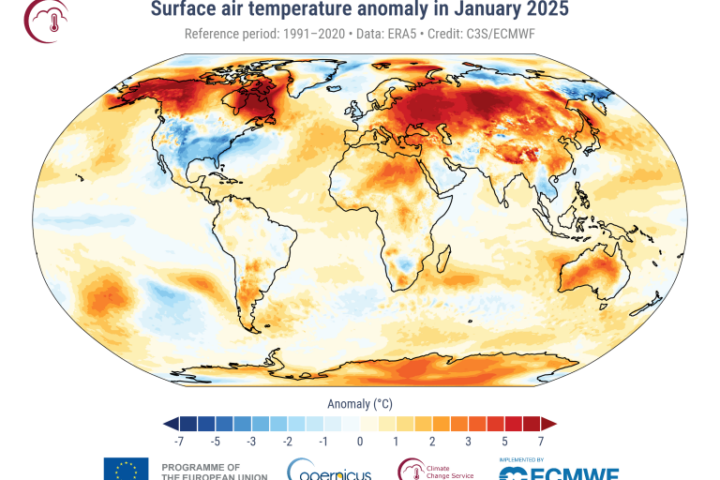

In a groundbreaking discovery that challenges our understanding of oceanic methane dynamics, a recent study led by an international team of researchers has shed new light on the vulnerability of deep-sea methane hydrates to climate change. Published in Nature Geoscience, the research, spearheaded by Professor Richard Davies from Newcastle University, reveals a startling migration and venting of methane from deep-sea hydrates on the Mauritanian margin.

Employing advanced three-dimensional seismic imaging over a vast 3520 km² area, the team uncovered that methane gas, previously believed to be stable, can migrate over distances as far as 40 kilometers below the hydrate stability zone. This revelation defies earlier beliefs, showcasing that a significant portion of the 96.5% of deep-water distal hydrates, far beyond the traditional 3.5%, could be susceptible to warming-induced release.

The study, which estimated the marine methane hydrate reservoir at approximately 1800 GtC (gigatons of carbon), points to a significant environmental concern. Professor Davies, reflecting on the discovery, stated, “It was a Covid lockdown discovery… Our work shows [the hydrates] formed because methane released from hydrate, from the deepest parts of the continental slope vented into the ocean.” This finding has major implications for global carbon cycles and climate change, suggesting that increases in bottom-water temperature can trigger methane release, especially in regions where hydrates exist at or below the seabed.

The study highlights the presence of 23 large pockmarks at the shelf break of the Mauritanian margin, indicating active methane venting, likely during warmer Quaternary interglacials. These pockmarks, ranging between 600-900 meters in width and 20-50 meters in depth, are significantly larger than those found at the landward limit of marine hydrate. The seismic data depicted margin-scale clinoforms, revealing deep-water mudstones interspersed with sands and silts, and a modern base of the hydrate stability zone (BHSZM) marked by a bottom simulating reflection (BSR).

Similar Posts

The research speculates on the role of climatic warming in reshaping the hydrate dissociation zone (HDZ) and influencing methane release patterns. The modeling of the past position of the BHSZ during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) aligns closely with the observed relict BSR, providing a historical context to the findings. This study underscores the need to reassess the role of deep-water hydrates in climate change models, considering their potential impact on methane venting in response to ocean warming.

The findings of this study are not just a matter of scientific curiosity but have real-world implications on how we understand and respond to the challenges posed by climate change. The release of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere, could have devastating effects on the planet’s climate, affecting millions of lives worldwide.

The research team, recognizing the importance of their findings, plans to continue investigating methane vents along the margin and predict future massive methane seeps as the planet warms. This forward-looking approach is vital in understanding and mitigating the effects of climate change. The study sets a new benchmark in interdisciplinary research, combining geological, oceanographic, and climatic data to offer a comprehensive understanding of undersea methane hydrate dynamics.