Even though wolves in Alaska can eat almost everything that moves, their menu is typically deer. As wolves on one island off the state’s coast devoured nearly all of the deer around them, they turned to an unexpected substitute: sea otters.

This is the outcome of a new study, which documents a unique occurrence of a wolf population surviving in the absence of large terrestrial prey like moose or deer. It also emphasizes the uncertainty of species restoration efforts on local food webs, as environmentalists have attempted to safeguard and return wolves and sea otters to southeastern Alaska’s glacier-carved coastline.

“Forever, we’ve just thought that wolves are largely tied to ungulates [hoofed mammals],” comments Layne Adams, a wildlife biologist at the US Geological Survey who was not involved in the study. “This is pretty phenomenal that one predator is basically living off of another predator in a different system.”

Small wolf populations have long been thought to be doomed in the absence of large herbivores to consume. In 1960, for example, a pack of gray wolves (Canis lupus) established itself on Coronation Island, a tiny isle off the Alaskan coast south of Glacier Bay National Park. The wolves devastated the island’s black-tailed deer population swiftly. Before turning to cannibalism, they shifted their focus to harbor seals. After 8 years, there was only one wolf left on the island, dooming its pack.

To the scientists’ amazement, wolves on adjacent Pleasant Island have escaped this fate. In 2013, the wolves swam ashore from the mainland and discovered a feast of Sitka black-tailed deer. Within a few years, the hungry wolves had devoured nearly all of the island’s deer. The Pleasant Island wolves, on the other hand, have persisted, unlike the Coronation Island wolves.

Between 2015 and 2020, a team of researchers gathered approximately 700 samples of wolf scat and hair to find out how. They also placed GPS collars to 13 wolves on the island and surrounding mainland to track their movements and establish where they were feeding.

The researchers discovered DNA from roughly 40 different species in the wolves’ scat, such as snowy owls, porcupines, halibut, and sperm whales. The most prevalent prey items, however, were Sitka black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus sitkensis, a stocky subspecies of mule deer) and, somewhat unexpectedly, sea otters (Enhydra lutris).

Humans had hunted sea otters out of most of Alaska’s coastline for centuries. However, reintroduction efforts and increased legal protection brought these marine creatures back from the brink of extinction—and onto the plates of wolves.

Deer provided over 75% of the wolves’ diet, according to samples taken in 2015. The researchers reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that by 2017, sea otters had become the wolves’ major prey. Otters accounted for roughly 60% of their diet, while deer accounted for only.

“The addition of sea otters has changed the game and allowed them to be sea wolves, living on primarily marine resources,” explains Taal Levi, an ecologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis and a co-author of the current study.

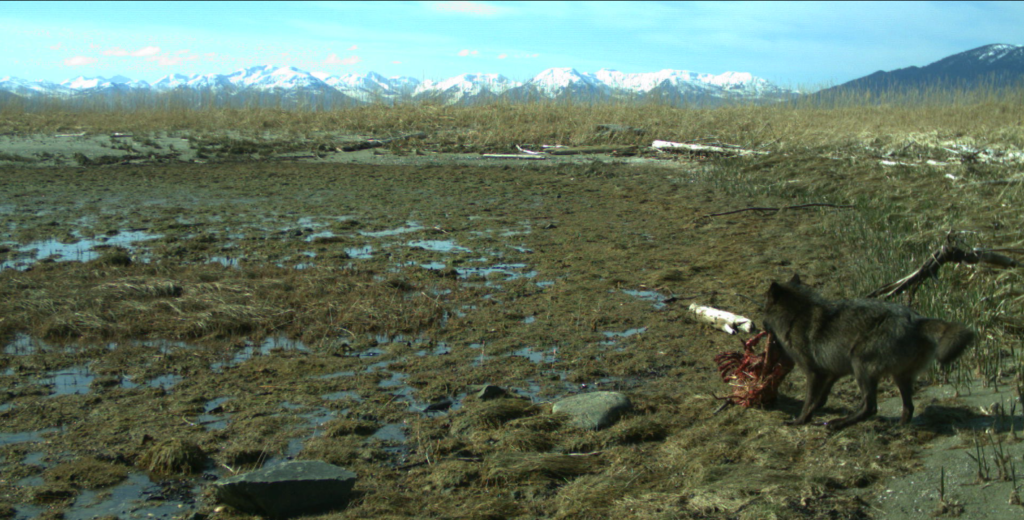

Swapping deer for otter flesh necessitated the intelligent canines devising a new hunting tactic. Sea otters, despite their cute look, are tough aquatic creatures with powerful claws and crushing teeth. When the animals congregate on the island’s rocky shores to rest, they become easy prey for wolves. The wolves, according to Gretchen Roffler, a wildlife biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and the study’s principal author, drag the sea otters over the high tide line to consume them. Roffler came across numerous gruesome otter carcasses with crushed skulls and broken spines while monitoring the wolves’ GPS collars.

Wolves do not only prey on sea otters on Pleasant Island. The researchers discovered evidence that mainland wolves consume a substantial number of otters. As local glaciers melt, sea otters have taken advantage of the newly available coastal real estate, putting them into closer contact with wolves.

Although the event has taken scientists by surprise, Levi believes the return of the two species in the region may be reuniting an ancient food web. “The restoration of sea otters is reinstating an ancient relationship between the sea and the land.”