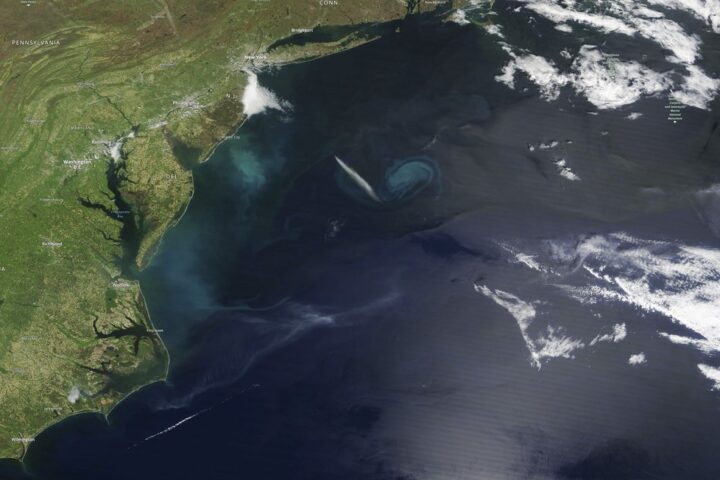

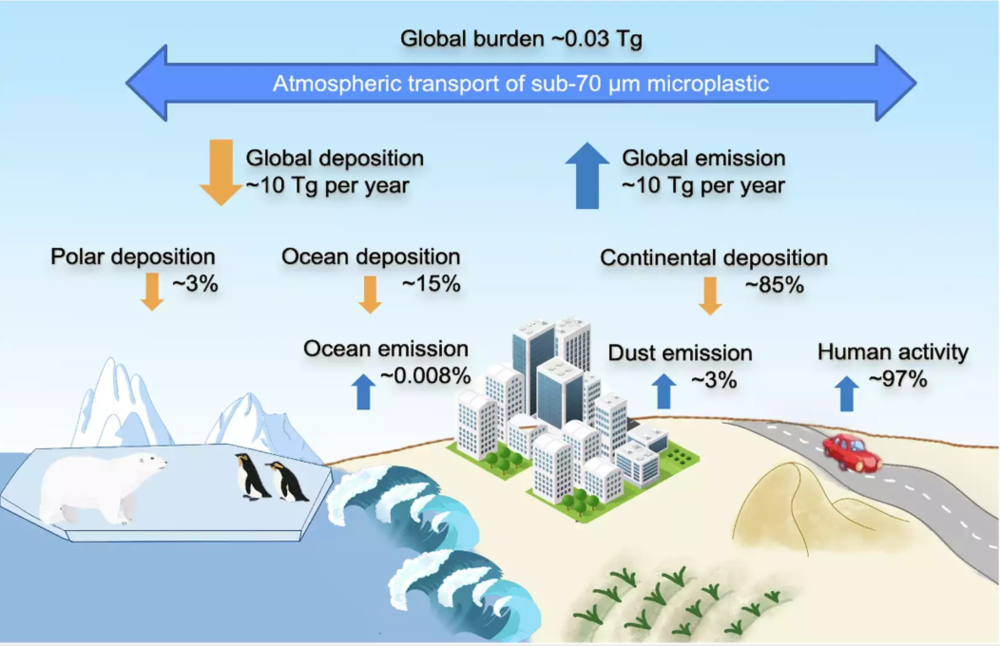

New research has flipped our understanding of how microplastics move through our environment. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology have discovered that oceans capture microplastics from the air rather than releasing them, contrary to what was previously believed.

Using advanced computer models to track microplastic movement globally, researchers found that oceans absorb about 15% of all airborne plastic particles. This challenges earlier theories that suggested oceans were pumping massive amounts of microplastics into the atmosphere.

“We used to think oceans might be releasing hundreds of millions or even billions of kilograms of microplastics yearly,” the research team notes. “Our laboratory experiments and models show it’s actually just thousands or hundreds of thousands of kilograms – far less than predicted.”

Published in npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, the study redirects attention to the real sources of airborne microplastics: land-based activities like vehicle tire wear, synthetic clothing fibers, and industrial manufacturing processes.

Size Matters: How Far Can Microplastics Travel?

The research revealed that a microplastic particle’s journey depends largely on its size. Larger particles tend to fall back to earth quickly, settling on land or near coastlines. But smaller microplastics can remain airborne for up to a year.

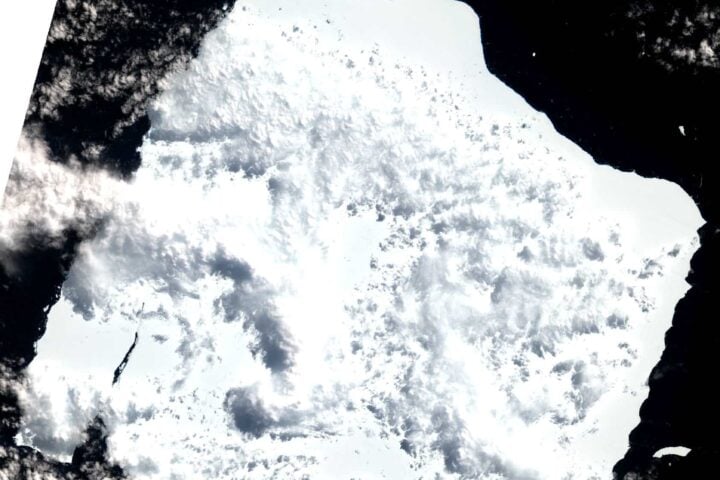

This extended flight time allows tiny plastic particles to travel thousands of kilometers, reaching even the most remote parts of our planet. Researchers found evidence of these particles in the Arctic, where they settle on snow and ice.

“Small particles, although emitted on the continent, travel as far as the Arctic region,” the study states, highlighting the truly global nature of this pollution problem.

Similar Posts

Health Concerns Grow as Research Advances

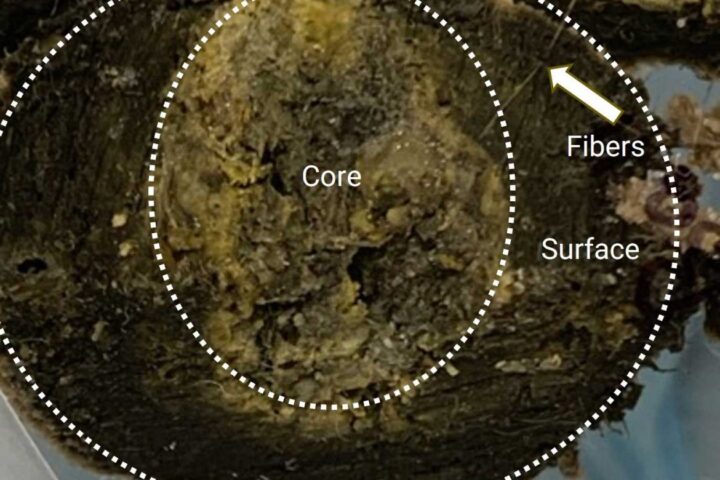

The widespread distribution of airborne microplastics raises serious health questions. When inhaled, these particles can cause respiratory issues and potentially enter the bloodstream. According to the source document, studies have found microplastics can cause inflammation, and researchers have mentioned potential links to neurological impacts.

Beyond human health, these particles pose environmental threats. When they settle on water bodies, microplastics can block sunlight, disrupting photosynthesis in aquatic plants and algae. This interruption threatens underwater ecosystems and potentially impacts our food supply.

Redirecting Our Efforts to Combat Plastic Pollution

This research suggests we need to rethink how we tackle microplastic pollution. Instead of focusing on oceanic sources, effective strategies should target land-based origins – reducing tire wear, improving synthetic fiber filtration, and enhancing industrial emission controls.

Many countries have already begun addressing plastic pollution through bans on single-use items and stricter recycling requirements. However, policies specifically targeting airborne microplastics remain rare.

Environmental organizations continue pushing for stronger international regulations and development of biodegradable alternatives to conventional plastics.

For individuals concerned about exposure, simple actions can help: choosing natural fabric clothing over synthetics and reducing unnecessary driving. While these steps alone won’t solve the global crisis, collective action at all levels – from personal choices to international policy – offers the best path forward.

Frequently Asked Questions

Microplastics are tiny plastic fragments smaller than 5mm. They’re concerning because they’ve been found everywhere—in oceans, soil, drinking water, and the air we breathe. When inhaled or ingested, they can cause health problems like inflammation and respiratory issues. In the environment, they disrupt food chains and can block sunlight needed by aquatic plants, threatening ecosystems that we depend on for food and oxygen.

The primary sources are land-based activities. Every time we drive, tiny particles wear off our tires. When we wash and dry synthetic clothing (like polyester), plastic fibers are released. Industrial facilities that manufacture or process plastics also emit particles directly into the air. Rather than oceans pumping microplastics into the atmosphere as previously thought, the research shows that oceans actually capture about 15% of airborne microplastics.

Yes, they can. When we breathe in microplastics, they can irritate our lungs and cause inflammation. According to the source document, microplastics can potentially enter the bloodstream. The source also mentions concerns about potential neurological impacts. While scientists are still studying the full range of effects, there are legitimate health concerns associated with exposure to these particles.

Surprisingly far! The research shows that while larger particles tend to fall back to earth quickly, smaller microplastics can stay airborne for up to a year. This allows them to travel thousands of kilometers, reaching remote locations like the Arctic and high mountain regions. This explains why researchers have found microplastics in places far from human activity—they’re literally floating in on the wind.

This study from the Max Planck Institute redirects our focus to land-based sources of microplastics. Previously, some researchers thought addressing ocean-based emissions might be key to reducing airborne microplastics. Now we know we should concentrate on reducing tire wear, improving how we handle synthetic fibers, and controlling industrial emissions. This means both policy approaches and individual actions need to target these primary sources rather than focusing on ocean emissions.

Several practical steps can help: Choose clothing made from natural materials like cotton or wool instead of synthetics when possible. When washing synthetic clothes, use cold water and shorter cycles to reduce fiber shedding. Consider driving less to reduce tire wear by walking, cycling, or using public transportation when practical. Avoid single-use plastics and support companies developing plastic alternatives. While these individual actions won’t solve the global issue alone, they do make a difference—especially when many people adopt them.