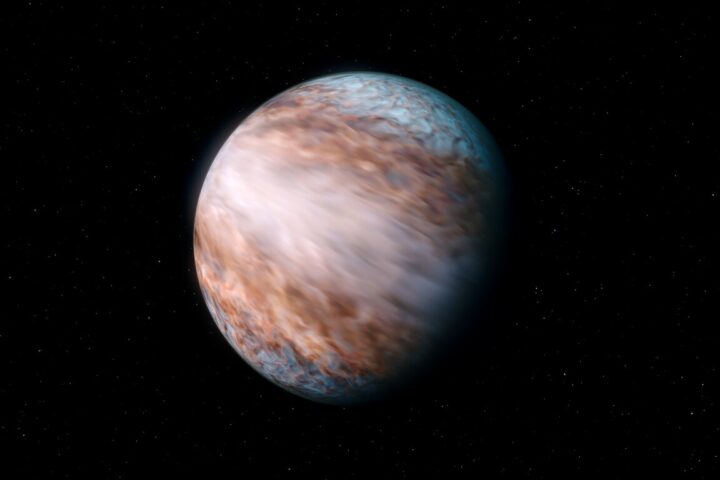

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has captured remarkable high-resolution near-infrared images of Lynds 483, a star-forming region 650 light-years away in the Serpens constellation. The images show two actively forming stars creating shimmering ejections of gas and dust that appear in orange, blue, and purple.

What Webb Discovered

The images reveal periodic ejections of gas and dust from the central protostars occurring over tens of thousands of years. These materials shoot out as tight, fast jets and slightly slower outflows. When newer ejections collide with older ones, the materials crumple and twirl based on their densities.

Chemical reactions within these ejections and the surrounding cloud have produced various molecules, including carbon monoxide, methanol, and other organic compounds.

“Webb’s sensitive NIRCam has picked up distant stars as muted orange pinpoints behind this dust,” NASA notes in their March 7 press release. The telescope’s extraordinary sensitivity allows it to detect features previously invisible to older instruments.

Star Formation Details

The two protostars at the center of the hourglass shape sit in an opaque horizontal disk of cold gas and dust so dense it fits within a single pixel of the image. Far above and below this flattened disk, the bright light from the stars shines through, forming large semi-transparent orange cones.

Particularly notable are the dark V-shapes offset 90 degrees from the orange cones. These areas appear empty but actually contain the densest surrounding dust, blocking most starlight.

Some jets and outflows have become twisted or warped. A prominent orange arc at the top right edge shows a shock front where ejections slowed after hitting denser material. Just below, where orange meets pink, the material appears tangled in new fine details that will require detailed study to explain.

Similar Posts

Scientific Impact

Astronomers will use these observations to reconstruct the history of the stars’ ejections by updating models to produce the same effects. They’ll calculate how much material the stars have expelled, which molecules formed during collisions, and the density of each area.

When these stars finish forming millions of years from now, they may each reach about the mass of our Sun. Their outflows will have cleared the surrounding area, sweeping away the semi-transparent ejections. What may remain is a small disk of gas and dust where planets could eventually form.

History and Context

Lynds 483 is named for American astronomer Beverly T. Lynds, who published extensive catalogs of “dark” and “bright” nebulae in the early 1960s by examining photographic plates from the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey. Her catalogs provided astronomers with detailed maps of dense dust clouds where stars form, serving as critical resources decades before digital files and internet access became widespread.

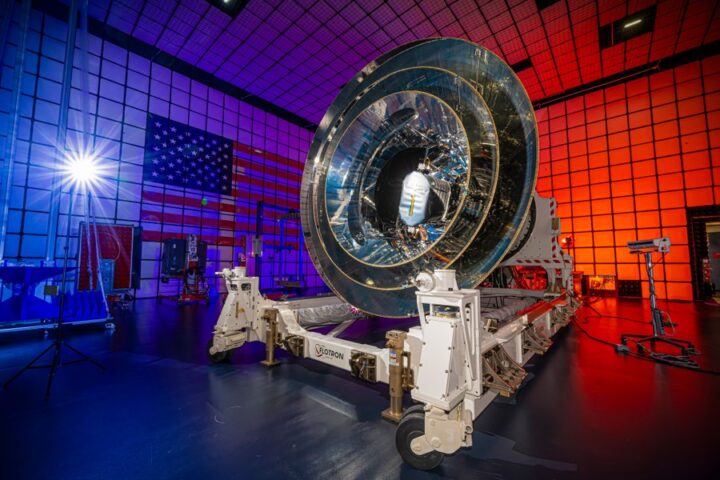

Upcoming Missions

NASA’s SPHEREx (Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and Ices Explorer) and PUNCH (Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere) missions aim to complement JWST by studying cosmic evolution, star-forming regions, and solar wind interactions. These initiatives reflect NASA’s ongoing focus on advancing our understanding of the cosmos.

What did the James Webb Space Telescope discover about Lynds 483?

Webb captured high-resolution near-infrared images of Lynds 483, showing two actively forming stars (protostars) creating shimmering ejections of gas and dust. The images reveal intricate details of how these stars periodically eject material over tens of thousands of years, creating jets and outflows that collide and form complex structures.

How far away is Lynds 483 and where is it located?

Lynds 483 is located approximately 650 light-years away from Earth in the Serpens constellation.

What molecules were found in the star-forming region?

Chemical reactions within the ejections and surrounding cloud have produced various molecules, including carbon monoxide, methanol, and several other organic compounds.

Who was Lynds 483 named after?

Lynds 483 is named for American astronomer Beverly T. Lynds, who published extensive catalogs of “dark” and “bright” nebulae in the early 1960s by carefully examining photographic plates from the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey.

What will happen to these forming stars in the future?

Millions of years from now, when the stars finish forming, they may each reach about the mass of our Sun. Their outflows will have cleared the surrounding area, sweeping away the ejections. What may remain is a small disk of gas and dust where planets could eventually form.

What makes the Webb Telescope’s images of Lynds 483 significant?

Webb’s unprecedented sensitivity and resolution allow it to capture details never before seen in star-forming regions. The images reveal fine structures in the ejected material, the interaction between newer and older ejections, and how light escapes through semi-transparent cones around the stars. These observations help astronomers better understand the early stages of star formation and the processes that eventually lead to planetary systems.