A new study published in Nature Communications has uncovered evidence that Neanderthals experienced a severe population crash around 110,000 years ago, which may have set the stage for their eventual extinction. This finding challenges previous assumptions about Neanderthal evolution and provides fresh insights into the demographic history of our closest evolutionary relatives.

Researchers from Binghamton University, the University of Alcalá, and the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont led the international team that made this discovery by examining a unique feature of Neanderthal fossils: the semicircular canals of the inner ear.

“The development of the inner ear structures is known to be under very tight genetic control, since they are fully formed at the time of birth,” explained Professor Rolf Quam from Binghamton University. “This makes variation in the semicircular canals an ideal proxy for studying evolutionary relationships between species in the past.”

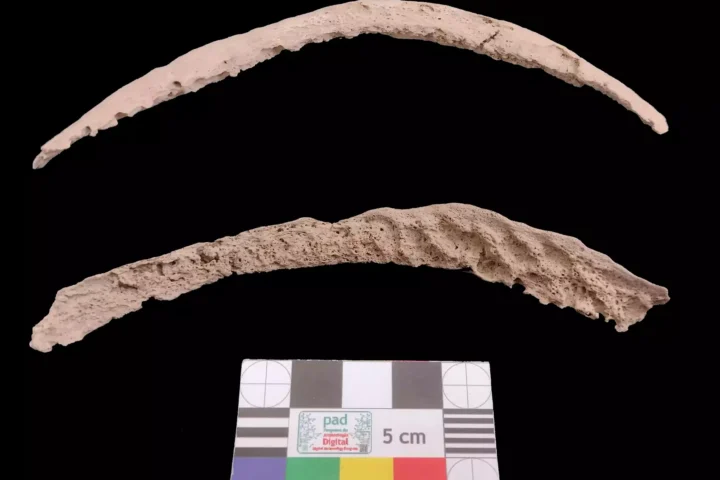

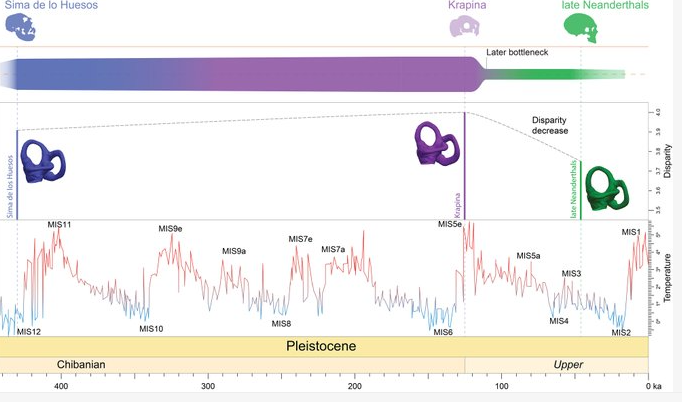

The team analyzed 30 Neanderthal specimens spanning nearly 400,000 years of evolution. They compared 13 “pre-Neanderthal” fossils from Spain’s Atapuerca site (dating to 430,000 years ago), 10 early Neanderthals from Croatia’s Krapina site (about 130,000 years old), and seven “classic” Neanderthals from France, Belgium, and Israel (64,000 to 40,000 years old).

The results showed a striking reduction in the diversity of semicircular canal shapes between the early Krapina Neanderthals and the later classic Neanderthals. This decreased variation reflects a loss of genetic diversity within the Neanderthal population, technically known as a genetic bottleneck.

“The reduction in diversity observed between the Krapina sample and classic Neanderthals is especially striking and clear, providing strong evidence of a bottleneck event,” said Mercedes Conde-Valverde, director of the Cátedra de Otoacústica Evolutiva at HM Hospitales and the University of Alcalá.

What makes this finding particularly interesting is that it aligns with previous research based on ancient DNA, which had also suggested a genetic bottleneck around 110,000 years ago. The timing coincides with significant climate changes in Europe, suggesting environmental factors may have played a role in reducing Neanderthal populations.

Surprisingly, the study found similar levels of genetic diversity between the oldest pre-Neanderthal samples and the early Neanderthals from Krapina. This challenges the previously held idea that Neanderthals experienced a population bottleneck at the beginning of their evolution.

“We were surprised to find that the pre-Neanderthals from the Sima de los Huesos exhibited a level of morphological diversity similar to that of the early Neanderthals from Krapina,” said Alessandro Urciuoli, lead author of the study. “This challenges the common assumption of a bottleneck event at the origin of the Neanderthal lineage.”

The research suggests that Neanderthal populations remained relatively stable and diverse for hundreds of thousands of years before experiencing a sudden decline around 110,000 years ago. This population crash would have made Neanderthals more vulnerable to environmental changes, disease, and competition from other human species.

Similar Posts

The study represents a methodological breakthrough as well. While ancient DNA analysis has previously helped identify genetic bottlenecks, this research demonstrates how inner ear morphology can be used to track population history – a valuable approach for older fossil samples where DNA preservation is poor or nonexistent.

For Brian Keeling, a graduate student at Binghamton University involved in the study, the project offered an exciting opportunity to be part of cutting-edge research. “As a student of human evolution, I am always amazed at research that pushes the boundaries of our knowledge,” Keeling remarked.

This new understanding of Neanderthal demographic history provides important context for their eventual extinction around 40,000 years ago. The genetic bottleneck 110,000 years ago may have left Neanderthals ill-equipped to handle subsequent challenges, foreshadowing their disappearance from the fossil record tens of thousands of years later.