Deep beneath Yellowstone’s steaming geysers, scientists have discovered something unexpected. Recent research has identified the northeastern section of the park as the most likely location for future volcanic activity, challenging previous theories about where the next eruption might occur.

Using special instruments that detect electrical signals underground, U.S. Geological Survey scientist Ninfa Bennington and her team found four distinct magma chambers. Among these, only the northeastern chamber maintains enough heat to keep magma partially melted over long periods.

“We suggest that the locus of future rhyolitic volcanism has shifted to northeast Yellowstone Caldera,” Bennington reports. This finding changes how scientists view Yellowstone’s volcanic system, which created a massive 30 by 45-mile crater during its last major eruption 631,000 years ago.

The research team used tools called magnetotelluric instruments, which work like underground X-rays, showing where molten rock sits beneath the surface. This method revealed that the northeastern magma chamber connects to deeper, hotter rocks, explaining why it stays warmer than other areas.

Similar Posts

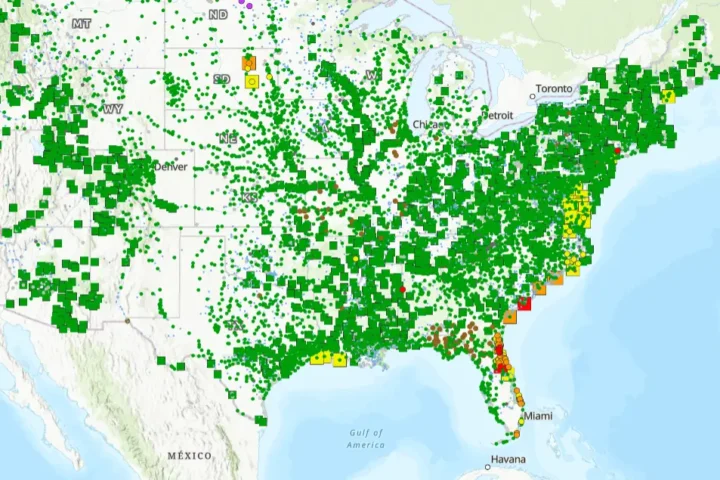

What does this mean for Yellowstone? The Yellowstone Volcano Observatory tracks daily activity across the park. Their measurements show typical patterns: ongoing low-level seismic activity and minor ground movement. These regular movements help maintain the system’s natural balance.

This discovery has practical importance. Park officials use this information to monitor geothermal areas. Scientists compare these findings with other massive volcanoes worldwide, like Indonesia’s Toba, which last erupted 74,000 years ago, to better understand how these systems work.

The northeastern chamber’s unique properties make it especially interesting to researchers. Its connection to deeper heat sources keeps the magma warmer than in other areas. Scientists track seismic activity, ground deformation, and gas emissions to understand what’s happening below.

Current measurements show no cause for immediate concern. The magma remains partially molten – conditions that don’t support an eruption. The regular release of heat through hot springs and geysers helps maintain this stable state.

Looking forward, this research helps scientists better monitor Yellowstone’s volcanic system. While the northeastern section might host future volcanic activity, such changes would take hundreds of thousands of years to develop. The new monitoring methods provide clearer images of underground conditions, helping scientists separate normal variations from concerning changes.

This improved understanding of Yellowstone’s underground structure helps scientists better assess risks and maintain public safety in one of America’s most visited national parks. Regular monitoring continues, providing ongoing updates about this complex natural system’s behavior.