I used to spill hot drinks and couldn’t even go into the kitchen,” says Kevin Hill, describing life before his new brain implant. Today, the 65-year-old Sunderland resident rides his bike, plays snooker with friends, and sometimes forgets he has Parkinson’s disease “for days and days.”

This remarkable change comes from a device called Brainsense – a small computer in the chest that connects to the brain. It’s about the size of a Jaffa Cake, connected to a brain implant no bigger than a grain of rice. When symptoms occur, it automatically sends electrical signals to control them, adjusting the treatment based on the patient’s needs.

“The tremors stopped instantly,” Hill recalls of the moment doctors switched on the device at Newcastle Hospital. His wife burst into tears at the sight of his steady hands – hands that had shaken uncontrollably for years, forcing him to quit his job and withdraw from social life.

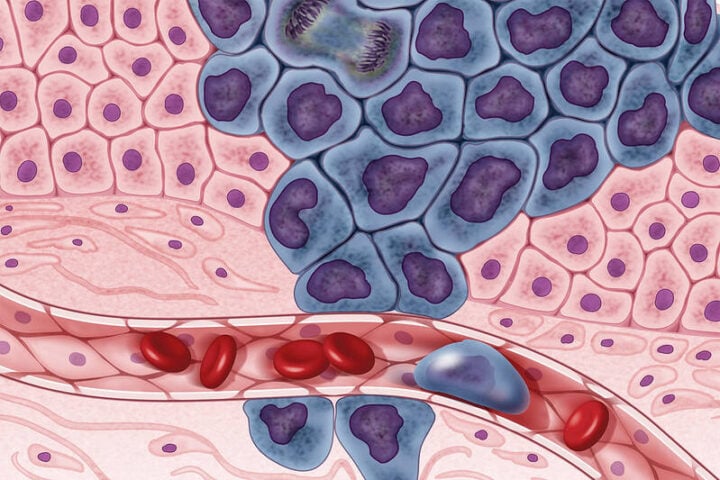

The technology works in two parts. First, there’s the small brain implant, connected by thin wires that run up the back of the neck. These wires carry signals to and from a computer in the chest wall. What makes this system special is its ability to read brain activity and adjust its treatment automatically, sometimes minute by minute.

Dr. Akbar Hussain, a neurosurgeon at Newcastle Hospitals who performs these implant surgeries, explains: “The electrical impulses provided to the brain by the device are controlled and adjusted automatically, according to individual patient’s recordings from the device in their chest. The biological signals generated within the person themselves are enough to alter the treatment given by the implant.”

Similar Posts

The timing couldn’t be better. About 153,000 people in the UK live with Parkinson’s disease, and this number is expected to grow as the population ages. The condition hits families hard financially – costing them around £16,000 each year while draining more than £2 billion annually from the UK economy.

This breakthrough joins other promising developments. At the University of Cambridge, researchers are working on a different type of brain implant using lab-grown brain cells called midbrain organoids. This £69 million project aims to rebuild brain circuits damaged by Parkinson’s. “Our ultimate goal is to create precise brain therapies that can restore normal brain function,” says Professor George Malliaras from Cambridge’s Department of Engineering.

Dr. Becky Jones from Parkinson’s UK adds perspective: “While evidence is still being gathered to assess the benefits of adaptive DBS versus the standard type, it’s great to see movement towards this becoming a new, more effective treatment for people with Parkinson’s.”

The impact on daily life can be profound. Before treatment, Hill’s tremors were so severe his wife banned him from the kitchen after he cut the end of his finger off while cooking. He couldn’t sleep properly and suffered constant pain in his shoulders, arms, and legs. The change after receiving the implant wasn’t just medical – it gave him back his independence.

The treatment at Newcastle Hospitals represents one of the first implementations of this adaptive treatment worldwide. His story offers hope to others living with Parkinson’s, showing how technology can help restore not just movement, but dignity and quality of life.

The success of this treatment also points to a future where brain disorders might be managed more precisely and personally. As Hill puts it, returning to activities he once thought lost forever: “To know that I’m going to benefit even more from having the latest version of the technology is just fantastic.